Why Canadians Should Care About Who Knows What

Veterans advocate Sean Bruyea realized something was wrong shortly after he appeared before a Parliamentary committee and spoke negatively about the provisions in the New Veterans Charter.

Bruyea was a Canadian Forces captain who had worked in military intelligence. He had served in the first Persian Gulf War and returned home with unexplained symptoms which were eventually diagnosed as combat stress reaction, the short-term version of post-traumatic stress disorder. Bruyea fought hard to convince the government that service in the Gulf had made him ill and he finally received a pension and treatment.

That experience turned him into an outspoken critic of the benefits and policies of Veterans Affairs Canada. “After I testified at a Parliamentary committee against the New Veterans Charter [in 2005], I found I was being cut off from communications,” he said. “It was both from the political side and from the bureaucracy side. They were trying to terminate my therapy and I found those in the bureaucracy who listened to me before were no longer receptive. I had to find out what was going on. I had to protect myself and my family first.”

To find out what was going on inside the bureaucracy he chose a complicated path; he made a request for information under Canada’s Access to Information Act.

Any Canadian citizen or permanent resident can ask about information in government documents as long as it isn’t protected by certain provisions in the law. The information can range from government studies and polls, to the individual’s personal information held by the government.

In Bruyea’s case, the process took two years, but he finally got what he requested—roughly 4,000 pages of material.

He discovered that hundreds of people had access to his files. Further, he found that his medical information with suggested therapy had been sent to Ste-Anne’s Hospital near Montreal which is the only veterans hospital still administered by VAC.

“They were trying to get me to go to the clinic they had in Montreal, but I had health practitioners in Ottawa that told me I didn’t need to go,” said Bruyea.

Of greater concern was the fact that briefing notes on his file had been prepared by the department for the minister. This prompted further requests as he tried to piece together what was being said about him. Eventually the file grew to roughly 14,000 pages.

“They outlined my medical information as well as my advocacy,” Bruyea said. He concluded that “basically, the department was trying to tell the minister, ‘This guy is not well, don’t listen to him.’”

Bruyea lodged a complaint with the Office of the Privacy Commissioner which in 2010 found that Bruyea’s personal information had been seriously mishandled. It also found that the department had many systemic flaws in the way it protected the information of the veterans, their dependants and survivors.

“Thank goodness we had a complainant with the courage to come forward and ask what was going on,” Assistant Privacy Commissioner Chantal Bernier told Legion Magazine in February.

Following that complaint, the Privacy Commissioner launched an audit of the department which led to significant changes in the protection offered to its clients.

The revelations led to then-Veterans Affairs Minister Jean-Pierre Blackburn offering a public apology to Bruyea in October of 2010. Along with the apology came a financial settlement which has remained confidential.

Bruyea’s case drew national media attention, and helped shine light on the two offices invested with protecting Canadians in the new age of technology: the Office of the Privacy Commissioner and the Office of the Information Commissioner.

Understanding the role of these two important offices begins with the basic question of what is public and what is private in today’s world.

With surveillance cameras now part of the landscape, and with Canadians in growing numbers revealing more about themselves through social media websites, the lines between keeping things private and going public are getting narrower by the minute. Yet almost everyone believes they have a right to privacy and a right to access information. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner and the Office of the Information Commissioner are helping to draw the lines between the two.

Both offices deal with a government that campaigned on a theme of accountability, and yet refused to release information on the costs of its tough-on-crime legislation and the purchase of F-35 jet fighters.

As a result, the government lost a confidence vote in the House of Commons in 2011, forcing a federal election. After winning the election with a majority, the Harper government seems content to march on, portraying itself as the most open government in Canada’s history.

The government’s own statistics, however, tell a different story.

The time to process access to information requests is getting longer and the documents that are released are heavy with black ink—redacting sections of information that are still not accessible. On the other hand, we have also seen how easily an individual’s privacy can be trampled on if protections fail.

Both the Privacy Act and the Access to Information Act are marking their 30th anniversary this year, and both are operating on 30-year-old legislation which new technologies have left behind. Yet the government is showing no sense of urgency in bringing the law up to date. All the while, the volume of information the government collects is growing and becoming faster to gather and cheaper to store.

The Information Age—A Brief History

The last quarter of the 20th century was named The Information Age. Like the Stone Age and the Bronze Age, it is defined by the technology that fuelled it, and the various challenges and adaptations that have occurred and will continue to occur along the way.

Today, Canadians spend more time online than the citizens of any other country, and so in a sense we are the most vulnerable to abuses. We use computers to send personal messages, to book flights and vacations, to learn about medical problems, file personal income tax, shop, pay bills, deposit money in our bank accounts, check movie times and find a romantic date. All of this activity generates information about ourselves, where we live, where we go, what we buy and what kind of entertainment we enjoy.

But the most voracious consumer of information is our own government. It keeps information on our passports, health, employment insurance, tax history and our prospects for old age security. The government is the most important storehouse of information about our society, and that information is often used to develop public policy.

It is also important to note that in order to participate fully in a democracy people must know—or be able to know—how government makes the policy or the decisions it does. That is the principle behind access to information. To truly understand one’s government requires vigilance on the side of the public, and co-operation on the side of the government.

Canada’s Access to Information Act has its origins in a bill first put before Parliament by Communications Minister Perrin Beatty in the brief government of Joe Clark. Although the bill died on the order paper when the government fell in 1979, Beatty—later an opposition backbencher—tried to reintroduce it as a private member’s bill without success.

Finally Pierre Trudeau’s government passed legislation building on policy already in place in Finland, Norway, Denmark, the United States and France.

The debate over access to information laws inevitably raised equally important concerns about the government’s interest in not releasing information that could threaten cabinet confidentiality, national security or could be a threat to an individual’s privacy which was protected in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The legislators passed two complementary laws: The Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. To administer those laws, they created the offices of the Information Commissioner and the Privacy Commissioner. Each commissioner is an agent of Parliament and acts as an ombudsman, with the authority to recommend, but not impose solutions to issues investigated. To perform these duties, each office has a staff that carries out investigations, tries to resolve complaints and monitors the performance of government institutions in complying with the act. The office also represents the commissioner in court cases and provides legal advice on investigations and legislative issues.

Access Denied

“There has long been an expression in the access to information world, paraphrased from our legal colleagues: access delayed is access denied,” wrote Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault in her May 2012 special report to Parliament titled Measuring Up: Improvements And Ongoing Concerns In Access To Information.

It is to the Information Commissioner’s office that a person can complain if they feel a government institution is not living up to its obligation to provide that information.

A federal department receiving an Access to Information Request must respond within 30 days. Departments can ask for an extension if the circumstances warrant it. “There are three main criteria that an institution can use to ask for an extension,” explained Emily McCarthy, Assistant Information Commissioner for Complaints Resolution and Compliance. “The first is if it would interfere with the day-to-day operations, because of the large volume of the request or other matters. The emphasis has to be on it being a ‘reasonable’ request for an extension.

“The second would be because there is a need to consult other institutions, either governmental or non-governmental,” she said. “The third would be if they have to give notice to a third party that has a commercial interest in the information.”

In 2011-12, the most recent figures available, the office handled 1,822 complaints, a slight decline from two years earlier when the office received 2,086 complaints.

Introducing The Accountability Act

Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party came into power in 2006 after more than 20 years on the Opposition benches, rallying against a Liberal government it considered secretive, even corrupt. The auditor general had found that millions of dollars had been spent on sponsorship and advertising activities in Quebec following the 1995 referendum on sovereignty with little or no work to show for it. Retired justice John Gomery was heading a royal commission into the spending which was uncovering just how poorly the money had been controlled.

The Conservatives had campaigned on a promise that it would make it a priority to pass what it called the Federal Accountability Act. “No aspect of responsible government is more fundamental than having the trust of citizens,” said the Speech from the Throne in 2006. “This new government trusts in the Canadian people, and its goal is that Canadians will once again trust in their government. It is time for accountability.”

Then-Treasury Board President John Baird introduced the bill on April 11, 2006, shortly after Parliament convened and the bill received royal assent on Dec. 12. It was a wide-ranging bill, touching many pieces of legislation and creating several new positions.

However, the idealism of that early bill soon clashed with the realities of being in power. One position created was the Parliamentary Budget Officer. However, Kevin Page, the first person to hold the position, had to take the government to court to have it hand over information on its austerity programs. A Commissioner of Conflict of Interest and Ethics was also created, and its first commissioner resigned after the auditor general revealed that the office had found no cases of wrongdoing in any of the 228 complaints it had received over three and half years. A Public Appointments Commission was also created as part of the Accountability Act, but seven years later it has yet to be put in place.

A portion of the Accountability Act added strength to the Access to Information Act by increasing the number of investigators and expanding the office’s jurisdiction over several Crown corporations and agencies, among them the CBC, Canada Post Corporation and the Canadian Wheat Board. It also extended jurisdiction over the Information Commissioner, the Privacy Commissioner, the Commissioner of Official Languages, the Chief Electoral Officer and the Auditor General.

The Accountability Act also codified the “duty to assist” for government departments, meaning that institutions must make every effort to respond to requests for information in a timely and complete manner. Yet in 2008-09—two years after the Conservatives took power—public institutions responded to fewer than 60 per cent of requests within the 30-day timeframe.

The Report Cards

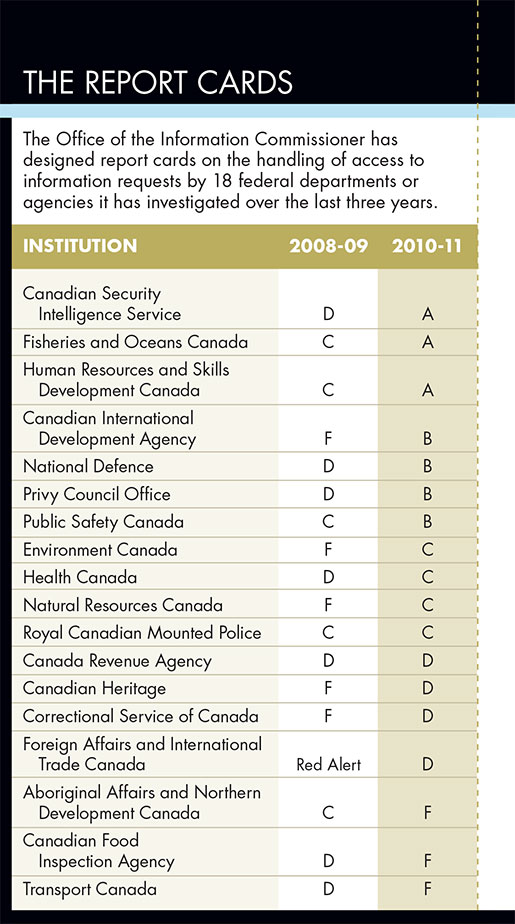

Twenty-four federal institutions that accounted for 88 per cent of all access requests to the government in the year 2008-09 were picked for scrutiny by the Information Commissioner’s office. Each one had at least five delay-related complaints.

Like schoolchildren, the institutions were given report cards ranging from A (Outstanding) to F (Unsatisfactory). The office developed a number of indicators of delay to develop a complete picture of workloads, procedures, resources and other factors that influence how quickly requests were handled.

The 18 institutions chosen for the 2010-11 report all had C or lower ratings in 2008-09.

The Issue of Transparency

During the early debates on access to information, Pierre Trudeau said “the democratic process requires the ready availability of true and complete information. In this way the people can objectively evaluate the government’s policies. To act otherwise is to give way to despotic secrecy.”

Yet secrecy often seems to be the way of many government departments, such the Department of National Defence. Certainly some information DND possesses should be protected for reasons of National Security or an individual’s privacy, but it should not be the modus operandi.

David Pugliese, a military affairs reporter with the Ottawa Citizen, has found that DND’s information providers have become so reluctant to release anything that access to information requests are one of the two main ways he gets information. The other source is leaks from disgruntled insiders. “I don’t think I’ve ever got a request [handled by the Department of National Defence] in 30 days. The worst is one I’m working with right now. It took eight years,” said Pugliese, adding that when he does receive documents they are often redacted. “Redacted isn’t a word I would use. They are censored.”

He said his use of the access laws comes in waves. “In the 1990s, when there was the Somalia inquiry, it was very hard to get information, so I used access to information often. After that things opened up until 2006 and now I’m using access frequently.”

Well after putting accountability at the top of its agenda, the government continues to present itself as devoted to transparency. In December, Treasury Board released its statistics on the government Access to Information program, announcing that the government was providing more access than ever before.

The government completed 43,664 access-to-information requests in 2011-12, nearly double that of 2002-03. “Technology has revolutionized access to information. It is not uncommon for a request to encompass 20,000 pages of government information and half a dozen departments,” said Treasury Board President Tony Clement in a news release that accompanied the statistical report.

There is no doubt the number of requests has increased, but in the same news release, Clement said: “Our government is the most transparent government in Canadian history. There has never been a time when Canadians have had as much access to government information.”

That claim, however, may seem hollow when looking at the numbers the report released.

“Obviously when it comes to timeliness, we are falling back. Now we are seeing requests answered in 30 days are at the 50 to 54 per cent range. If you go back 10 years ago we were doing much better,” said McCarthy.

Indeed, the report notes that the government now completes 55.3 per cent cases in the required 30 days or less, but in 2002-03 that figure was 69 per cent. Requests taking 121 days or longer to answer accounted for 10.5 per cent of requests. That number was only 7.9 per cent in 2002-03. As well, fewer requests were being answered within 30 days in 2011-12 than in the previous year.

The Un-Release Incident

While the government claims it is the most transparent government in Canadian history, a perception of secretiveness exists. It is routine for access managers to give a “heads-up” to the minister’s office when material being released might lead to controversy or questions in the House of Commons.

McCarthy believes it is important that the access be managed at the senior level. “We recommend that managing access be delegated by the minister to the deputy minister.” It would then be for the deputy minister to invest that authority in a senior manager, at a level high enough that he or she could authorize the release of the information without having to consult a higher level.

That, however, can prove awkward—if not very risky—for the employee tasked with processing the requests.

“Access to information can be a career killer to someone doing the work,” explained Sharon Polsky, president of the Privacy and Access Council of Canada, a professional body representing federal and provincial practitioners in privacy and information across Canada. “Releasing the information goes right up to the minister’s office, I am told.”

A high profile incident at Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) showed how interference is possible if it is not reined in.

A Canadian Press reporter made an access request for an annual report on the government’s vast real estate holdings. The material was found, copied and prepared to be sent to the reporter when a routine message was sent to the minister’s office. Sebastien Togneri, an aide to the then-minister Christian Paradis, received the message and demanded to know where the material was.

He was told that information was in the mailroom waiting to go out in the mail. “Well, un-release it,” Togneri said in an e-mail dated July 27, 2009.

The actions at PWGSC led to an investigation by the Information Commissioner’s Office, and hearings on Parliament Hill. The Information Commissioner then discovered that the material was retrieved from the mailroom, and 107 pages were removed from the 133-page document.

Togneri resigned over the scandal and the commissioner eventually forwarded the information to the RCMP for a possible criminal investigation. In August 2011, the RCMP dropped the investigation saying it wasn’t warranted.

“Canada is not a good place to be for access to information,” said Polsky. “There was a time when other countries looked to Canada on these issues. Now, they want to avoid Canada’s mistakes.”

The Information The Government Needs

Having access to all this information on its citizens means the government has another, equally important, responsibility—the need to keep the information it gathers on its citizens private. That is the concern of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner.

“[Canadians] spend an average of 43 and half hours online every month—almost twice the global average. We are also among the most enthusiastic users of social media. Roughly one in two Canadians is on Facebook,” Privacy Commissioner Jennifer Stoddart told an Ottawa audience in 2011.

The social medium Facebook became a focus of the office when it became concerned that Facebook was sharing too much information with third party developers of Facebook applications such as games and puzzles. There were no adequate safeguards to restrict the more than one million developers around the world from accessing users’ personal information along with the information of their online friends.

The office’s jurisdiction in the private sector was extended in stages between 2001 and 2004 with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). Under PIPEDA, organizations that gather information, including subscriptions, memberships and client lists, must make all reasonable attempts to safeguard the public’s privacy.

In negotiating with Canada’s Privacy Commissioner, Facebook agreed to retrofit its application platform to prevent any application from accessing information until the user obtains the expressed consent for each category of personal information it wants to access. There would also be an online link to the developer with a statement on how that data would be used.

Facebook also agreed to provide clear information explaining the distinction between account deactivation, which is when personal information is held in storage, and account deletion when the information is actually erased from Facebook servers.

Other privacy protection authorities have built on Canada’s work. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission reached a settlement with Facebook which requires the network to undergo regular privacy audits for the next 20 years. “What has changed over the past few years is the complexity of the issues we are investigating,” noted Assistant Privacy Commissioner Bernier.

A Veteran’s Case

Sean Bruyea’s case was an example of that complexity. The Privacy Commissioner’s office concluded that “the volume and sensitivity of personal information, including medical information, contained within two briefing notes to the minister was excessive and went far beyond what was necessary for the stated purposes of the briefing.” It also found the complainant, Bruyea, had never consented to having his information transferred to Ste-Anne’s hospital.

In light of its findings the commissioner’s office launched a full audit of the department. It found that the amount of information VAC handles is overwhelming. It provides services to more than 200,000 clients who include veterans, their dependants and survivors. The files of these clients may contain military service records, employment and education history, medical and financial information. The unauthorized uses or disclosure of that information could lead to identity theft, financial loss, humiliation or damage to reputations or risk to personal safety.

The Privacy Commissioner’s office reviewed the department’s “personal information management policies, procedures and processes, program records, guidelines, privacy impact assessments, security reviews, training materials, information sharing agreements and contracts with third party service providers.” It also sampled veterans’ files and examined the ways the department assigns responsibilities and manages risks and ensures compliance with obligation under the Privacy Act.

As a result of the complaint report completed in the fall of 2010 and the audit, Veterans Affairs Canada took a proactive approach and quickly developed on its own a 10-point action plan, most of which was completed by March 2011.

At the heart of gathering information is the Client Service Delivery Network (CSDN), a computerized system which brings together all of a veteran’s files for determining pensions, medical treatment or awarding medals. It can be used by caseworkers helping a veteran through the pension system or it can be accessed by the workers at VAC’s call centres who help veterans check on their cases. During the audit, the commissioner was able to confirm that access to the CSDN had been removed from 45 positions or 499 employees—presumably tighter access that represents a significant step forward.

Other revelations found during the audit had to do with the retention of information. The commissioner’s office found that the CSDN did not have the technical capability to dispose of information. That meant everything added to the network remained there indefinitely.

The final report released in October 2012 noted that the audit found that the department was taking its obligations under the Privacy Act seriously. “I think VAC really tried to improve in most areas but we still had 13 recommendations after our audit,” said Bernier.

Since that time, VAC has completed its 10-point plan and introduced a second phase of that plan called Privacy Action Plan 2.0. “I think [the audit] has been a wake-up call. Leadership from the top was crucial,” said Bernier.

While VAC is being very open about how it has changed the way it manages the privacy of files, a sign of how information is still controlled from the top was seen when Legion Magazine asked for an interview with a senior member of the VAC staff who had responsibility for the privacy policy.

No request was made to Veterans Affairs Minister Steven Blaney’s office. Yet, half an hour before the telephone interview with Acting Assistant Deputy Minister Charlotte Stewart was about to begin, the magazine received an unsolicited e-mail from Blaney’s director of communications, Niklaus Schwenker.

“Minister Blaney and our government take the privacy of veterans extremely seriously. That is why we have brought forward the most sweeping privacy improvements in the history of the department, including the 10-point Privacy Action Plan and Privacy Action Plan 2.0,” wrote Schwenker. “As per the minister’s direction, the department is implementing all of the Privacy Commissioner’s recommendations as it continues to take action to ensure privacy practices meet the highest standards. In fact more than half of the audit’s recommendations have been fully addressed, and the remaining actions are well underway.”

When Stewart was reached in Charlottetown she said the department made a commitment in 2010 to review its privacy policies and has built on the recommendations from the Privacy Commissioner. “Access to the CSDN is essential for our employees to make good decisions,” she explained, adding that the system has been improved, so that when an authorized employee goes on the system, a box drops down with the options for the user to check to explain why the files are being accessed.

Contracts with third party service providers, such as companies that shred and dispose of files, have also been altered. “All our contracts have a clause in them that the contractor will follow certain rules to protect the privacy of those files and they are bound by that contract,” said Stewart.

In addition, the department is doing more to educate staff on privacy issues. “In all our training programs now, there is a chapter on privacy issues,” added Stewart.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner has said it will again look at VAC’s progress in two years, but for 2013 it will concentrate on other investigations.

The Surveillance Society

While some federal ministers say privacy is top priority, the government still seems to have a way to go.

The obvious example is the Harper government’s attempts to introduce a law which would make Internet providers hand over information on its clients’ usage without a warrant. Introduced in different forms during the minority governments, the bills all died on the order paper. But with a majority government, the legislation was brought back in February 2012, as the Protecting Children from Internet Predators Act.

Making its way through Parliament as Bill C-30, the bill would have given police and other government officials the authority to make Internet providers disclose information related to clients’ Internet addresses without a warrant.

When challenged by an opposition MP on the privacy provisions in the House of Commons, Public Safety Minister Vic Toews famously retorted, “He can either stand with us or with the child pornographers.”

In an open letter to Toews released in October 2011, Commissioner Stoddart wrote of the previous bills, “I am concerned about the adoption of lower thresholds for obtaining personal information from commercial enterprises. The new powers envisaged are not limited to specific, serious offences or urgent or exceptional situations. In the case of access to subscriber data, there is not even a requirement for the commission of a crime to justify access to personal information—real names, home addresses, unlisted numbers, e-mail addresses, IP [Internet Protocol] addresses and much more—without a warrant. Only prior court authorization provides the rigorous privacy protection Canadians expect.”

The outcry over the bill was enough to stall it in the House for a year. Then in February this year, Justice Minister Rob Nicholson announced to reporters without any fanfare that the government would no longer proceed with Bill C-30.

Other examples of planned intrusions on the public’s privacy have been uncovered by the Commissioner’s Office. It was able to shed light on a program called the Longitudinal Labour Force Survey put together by Human Resources Development Canada. It had quietly amassed as much as 2,000 pieces of information each on 33.7 million Canadians, many of whom had already died. It was exposed in the office’s 1999-2000 annual report and was quickly shut down.

Preferring to operate proactively, the Treasury Board introduced privacy impact assessments (PIA) which required departments to examine the privacy effects of new or significantly altered programs or activities. The PIAs are reviewed by the office to ensure there is a pressing and substantial public goal rationally connected to any activities that infringe upon privacy.

For example, the RCMP in British Columbia developed a program for automated licence-plate recognition. Video cameras in marked and unmarked police cars combined with pattern identification software were used to identify license plates on parked and moving vehicles. More than 3.6 million plates were recognized in the two-and-a-half-year period after the program began in 2007.

The plate numbers were cross-checked against databases containing lists of stolen vehicles, suspended drivers and uninsured vehicles. A match or a “hit” triggered further investigation and police interventions, but fewer than two per cent of the plates checked produced hits. The PIA showed that information on plates that did not have a hit was being retained, building up files on law-abiding Canadians for no apparent reason. As a result the RCMP agreed to stop retaining the information.

The travelling public, meanwhile, can be somewhat relieved by a pro-privacy intervention aimed at the millimetre-wave imagers introduced to screen passengers about to board aircraft. Once inside the imager, clothing and many other materials become translucent so that the operator can detect any hidden weapon or banned substances. The imagers have been called “virtual strip searches” because they allow the operator to see the surface of the skin under the clothing, including prosthetics and other hidden medical devices such as colostomy bags. The intervention resulted in the technology being used for secondary screening, and only as a voluntary option to a traveller who would otherwise undergo a physical pat-down.

Issues of airport security have crossed the desk of the Privacy Commissioner a number of times. The Canadian Air Transport Security Authority also introduced the Passenger Behaviour Observation pilot project which ran over a five-month period in 2011 at Vancouver International Airport. The project placed specially trained officers in a position to observe passengers and look for suspicious behaviour as they waited to go through a security checkpoint. The review of the PIA, which included sending staff to the airport to watch the project in action, caused the Privacy Commissioner’s office to raise concerns about the potential for inappropriate risk profiling based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender and age.

The Right To Correct

Another important aspect to the privacy law is protecting an individual’s right to know what information the government has about them and the individual’s ability to correct that information.

“It is a fundamental right,” said Bernier. “Look at the case of Maher Arar. They had lots of information on him, but it was wrong and look at the consequences.”

Arar, a Canadian who was born in Syria, was an engineer living in Ottawa in 2002. While returning from a vacation in Tunis he was arrested at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. U.S. authorities deported him to Syria where he was thrown in jail and tortured.

A judicial inquiry headed by Justice Dennis O’Connor found Arar had no links to terrorist organizations or militants. He also found that the RCMP had given misleading information to U.S. authorities which may have led to his being deported. The federal government reached at $10-million settlement with Arar in 2007 and Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an official apology.

Looking Ahead

The privacy commissioner has told several parliamentary committees that the Privacy Act is a 30-year-old piece of legislation created in a paper-based era. Canada was one of the first countries in the world to create privacy protection authority and yet major rewrites of similar legislation are underway in Australia and Europe. The European Commission is currently re-examining its 1995 directive on privacy protection.

The office has 12 points it wants to see updated or added to the legislation. Many of them are there now in practice, but not in legislation. This would include giving the office a clear mandate for public education and embedding a necessity test which would require government institutions to demonstrate the need for the personal information they collect.

However, no Parliamentary committee or government department has undertaken to bring either the Privacy Act or Access to Information up to date. To do so would no doubt expand the offices’ authority, which is not in the interest of a government that has an almost passive-aggressive attitude to these issues.

Polsky is not surprised at the government’s indifference to updating the acts which govern the offices of the Information Commissioner and the Privacy Commissioner. As she puts it, “It is not to the government’s advantage to have access available.”

Necessary Vigilance

Sean Bruyea’s ordeal essentially ended with the apology and the settlement.

He is now studying for his master’s degree. He is interested in the military and how it has treated its veterans throughout history. “My advocacy has not stopped. I’m just pursuing it in a more academic way,” he said. “My wife and I have had our first child. We were trying before but there was just too much stress.”

When the system stopped working for him he was able to turn to the two offices that support access to government information, and the privacy of its citizens.

The 17th century philosopher Francis Bacon affirmed, “Knowledge is power.” In a democracy, the people are supposed to have the power. An informed public is clearly an essential element as is the privacy which allows people to exercise their freedom without fear that a government can use the information it has to threaten or censor.

The freedom our veterans fought for has proven a lasting legacy, but it is one that requires constant vigilance—not only from threats from foreign shores—but from the very institutions we have set up to govern us.

Advertisement

![[ILLUSTRATION: DOUG PANTON]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Privacy1.jpg)

![[ILLUSTRATION: DOUG PANTON]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Privacy2.jpg)