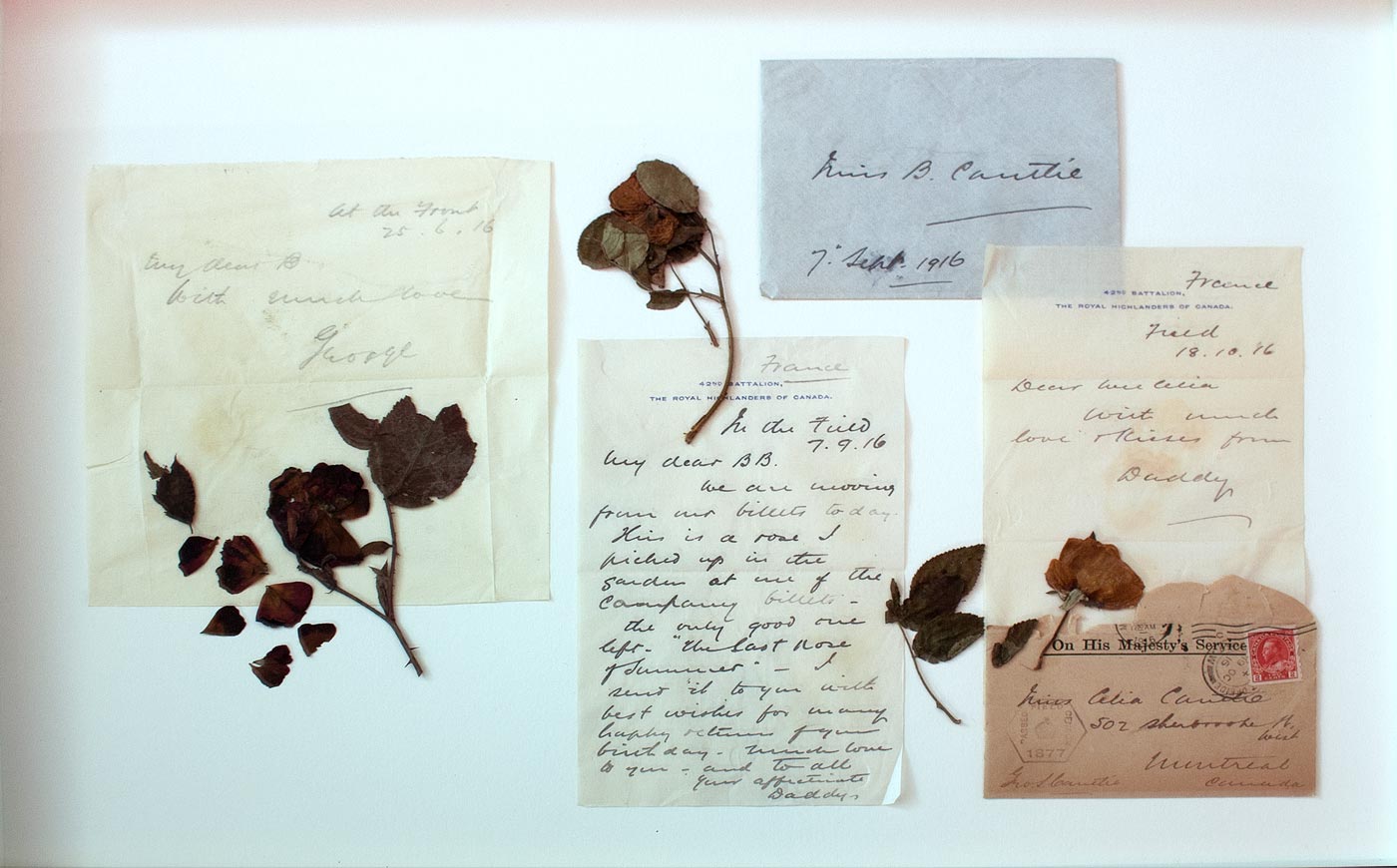

An assortment of letters and flowers that inspired the WAR Flowers exhibit. [warflowers.ca]

Almost a century later, those handwritten letters and flowers emerged in a red satin-covered box still in their original envelopes, and now form the basis of a unique touring exhibition, which opened last week at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

“Dear Wee Celia,” says one bearing pressed daisies and dated At the Front, 28.6.16. “From the trenches and shell holes with much love from Daddy.”

Another, written on field message paper, imparts “much love” with pressed poppies picked “At the Front, Flanders, 1916.”

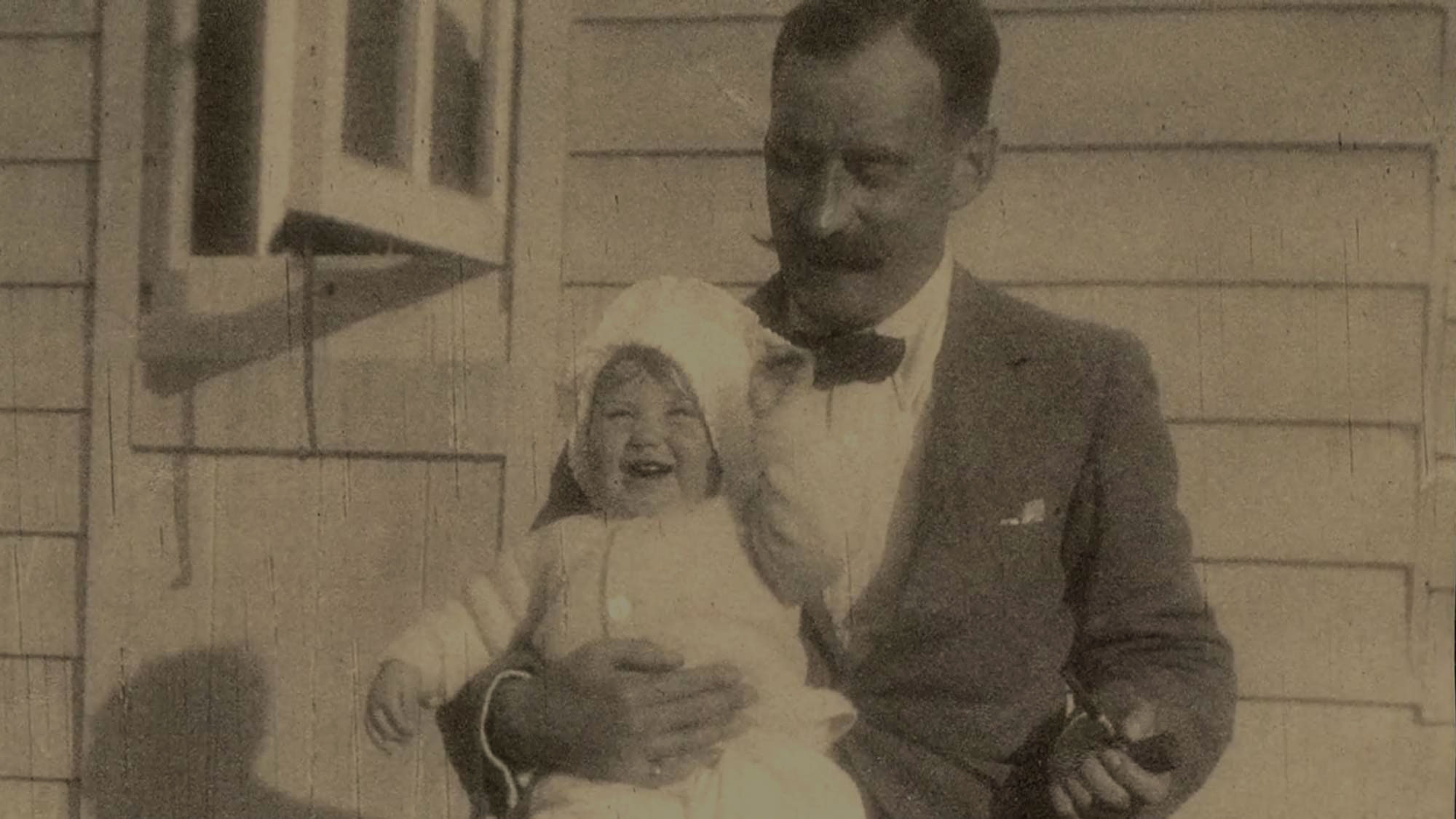

Cantlie wrote two letters nightly—one to his wife and a second to one of his five children. Celia was the youngest. She was one year old when her father shipped out in 1914. He wanted her to have something she would remember him by should he not return.

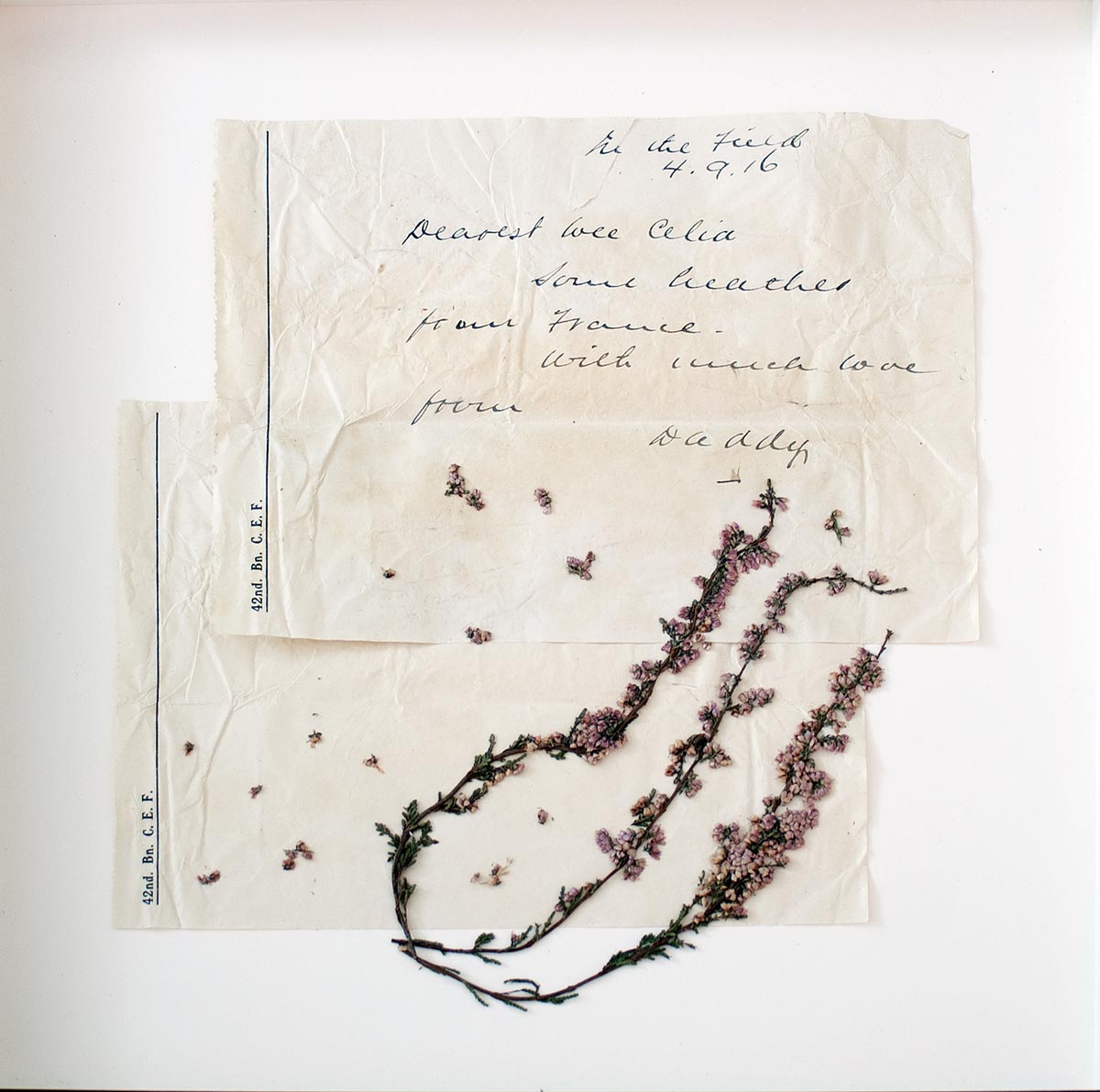

“He was a sentimentalist and he loved flowers,” Cantlie’s granddaughter, Grace Elspeth Angus, says in a video accompanying the exhibition. “During the day, between bivouacs, he would pick a flower, no matter what it was…and press it in a book.

“When the thing was dried, he’d…put it in an envelope and send it to his baby daughter.”

Cantlie and his daughter Celia. [warflowers.ca]

“I am not a botanist—I barely own a cactus, let me tell you—but when I saw the letters and the flowers, I knew that we were looking at a narrative that was important,” Melki said.

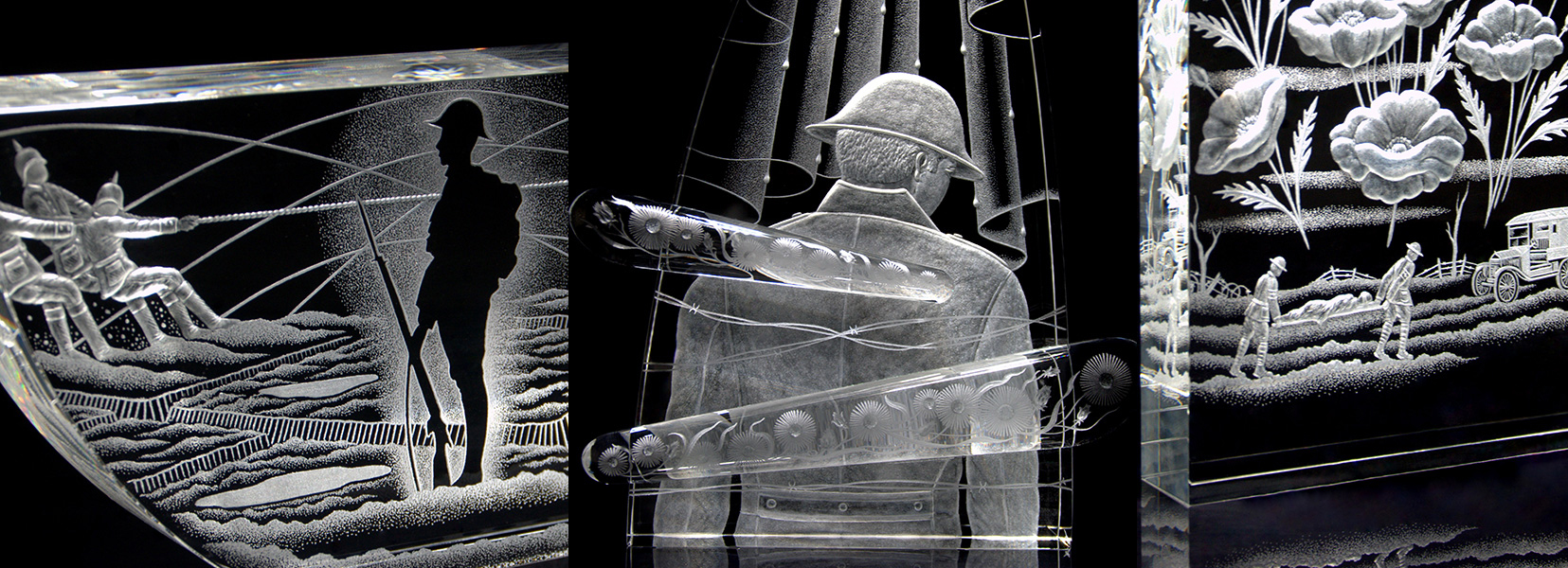

Working with Jardins de Métis/Reford Gardens in Grand-Métis, Que., Melki developed a novel exhibition based on “intimacy and emotional attachment” that combined Cantlie’s touching dispatches with scents, sounds, sculpture and floriography, a Victorian-era method of interpreting meaning from flowers.

The daisy is innocence; the poppy, eternal rest. There are yellow roses (familial love), pink roses (grace), heather (solitude) and others. There were more than 300 letters in total. Ten to Celia, all with flowers and most written during the Battle of the Somme, form the basis of the exhibition.

A letter containing heather sent from Cantlie to daughter Celia. [warflowers.ca]

There is the story of Edward Savage, who raised a militia and triumphed at Vimy Ridge. He made it home to dance one last time with his beloved wife Marion in Montreal before he lost his final battle, with the Spanish flu during the epidemic of 1920. His story and picture are linked to lavender (devotion).

Each station displays a small collection of artifacts—uniform buttons, shrapnel from Flanders, rings fashioned by soldiers in the trenches—along with a specially commissioned crystal sculpture by Toronto artist Mark Raynes Roberts and a scent developed by perfumer Alexandra Bachand of Magog, Que.

Examples of the exquisite crystal sculptures by Mark Raynes Roberts. [warflowers.ca]

“It’s really writing with scent, an olfactive narrative,” says the European-trained Bachand, one of barely a handful of perfumers in Canada. “It’s like a way to build a bridge with an image, with the story. It helps you to feel it, to have emotion.

“Sometimes one can feel some distance with archival material and historical content. With the scents, it brings it all together. It immerses you in the story. It makes you live it. It is really an authentic and poetical way to tell a story.”

The creative team travelled to France to “live” the stories they would tell and familiarize themselves with the battlefields and cemeteries.

Melki was born to Brazilian and Lebanese parents in The Gambia in West Africa and educated in England. Her earliest memories are of war. Now living on the Gaspé Peninsula, she has spent 12 years putting history to film.

“I worry every day—at night, I go to sleep and I think about history disappearing,” she says. “I’ve made it my goal and my contribution. This is how I contribute to society: I make history projects.”

She is a gifted fundraiser and organizer in a time when money for arts and history alike is scarce. She has a knack for recruiting talented artists for projects and getting those projects seen.

“As the land is eroding, so is history,” she says. “We have to hold onto it; we have to tell those stories.”

Cantlie survived the war. He suffered what was then called battle fatigue and was sent home in 1917. His daughter Celia grew up adoring him, as did his granddaughter, Elspeth, to whom Celia bequeathed the red box.

The exhibition runs at the Canadian War Museum’s Regeneration Hall through Jan. 7, 2018.

Learn more about the exhibit at: https://warflowers.ca

Advertisement