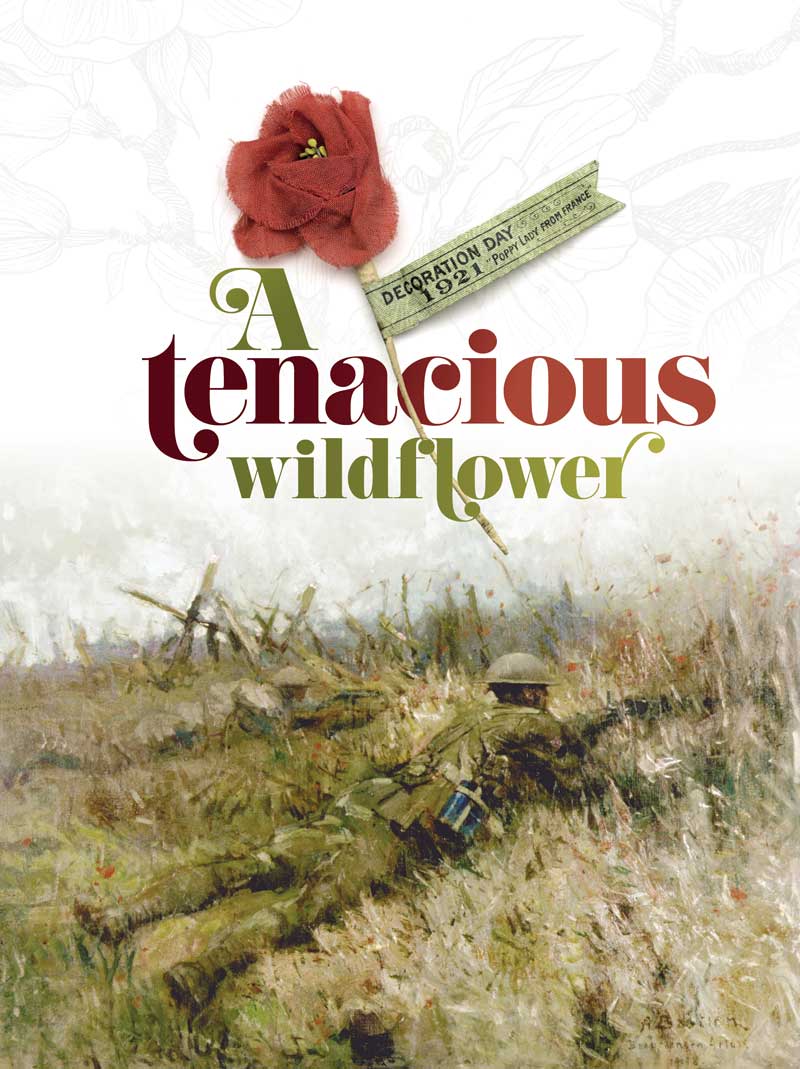

The poppy (Papaver rhoeas) persevered near trenches and no man’s lands in Belgium and France. A hand-made poppy lapel pin was distributed by the American Legion in 1921. [CWM/19720228-001; Lieut. Alfred T.J. Bastien/CWM/19710261-0055]

Each year, The Royal Canadian Legion distributes about 20 million poppy lapel pins across Canada. The poppies are given freely, with people encouraged to donate to the poppy fund in support of veterans in need. But this November, many Legionnaires will be wearing a different type of poppy pin—one that resembles one of the first poppies worn in remembrance 100 years ago.

The poppy campaign in Canada has its roots in the First World War. The inspiration for the campaign was the poem “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae, a doctor serving with the Canadian artillery in Belgium in 1915.

During the Second Battle of Ypres from April 22 to May 25, 1915, McCrae’s friend Lieutenant Alexis Helmer was killed by an artillery shell. McCrae conducted an impromptu funeral for his friend, reciting as much of the Anglican Burial of the Dead service as he could recall.

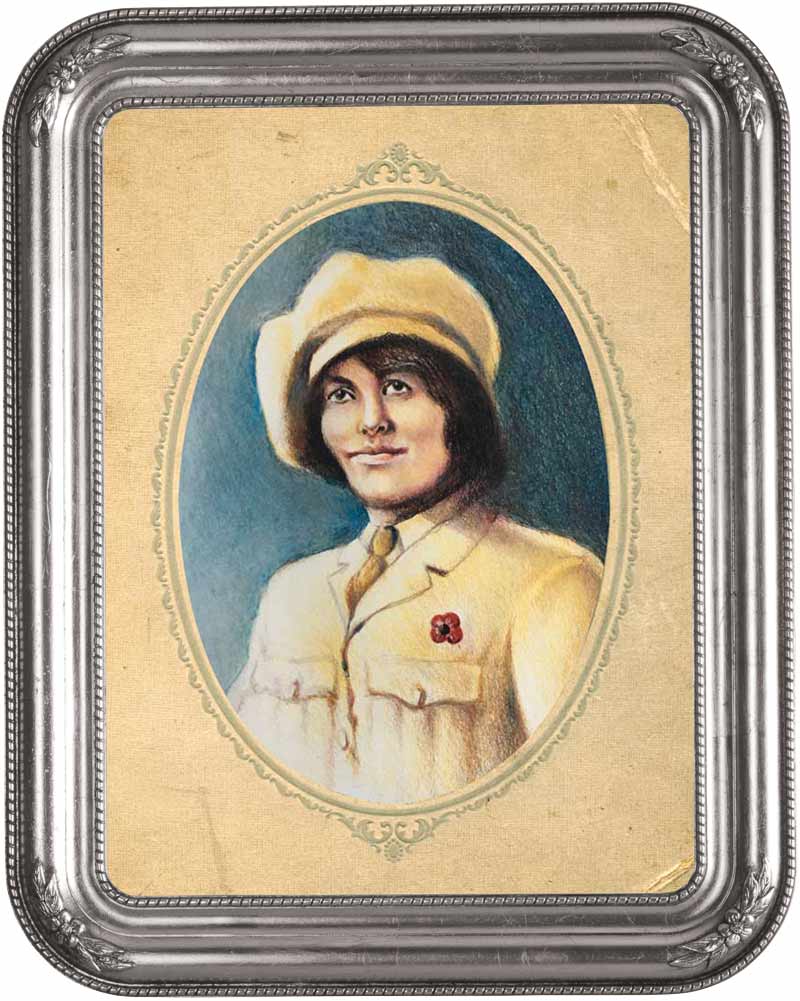

Credit for creating the poppy campaign generally goes to two women.

Later that day or the next, McCrae wrote the 15-line poem about the tenacious little wildflower that flourished in the turmoil of the battlefield, churned up by constant shelling and littered with the bodies of men and horses.

After being rejected by one of the mainstream newspapers in Britain, the poem was published anonymously in the humour magazine Punch in December 1915. It quickly became popular with the troops serving in France and Belgium. In Canada, it was used in a federal election and to help sell war bonds.

Even though the author of the poem that inspired the campaign was Canadian, credit for creating the poppy campaign generally goes to two women—one French and one American.

Moina Michael conceived of wearing a poppy to commemorate the Armistice. [Georgia Museum of Art/2018.127]

The American was Moina Michael, who worked for the YMCA Overseas War Secretaries’ headquarters in New York. She wrote a poem answering the challenge McCrae offers in his poem:

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

Entitled “We Shall Keep the Faith,” Michael’s poem appeared in the Ladies Home Journal in November 1918. Its closing lines are the answer to McCrae’s challenge:

Fear not that ye have died for naught;

We’ll teach the lessons that ye wrought

In Flanders Fields.

Michael later started to campaign promoting the idea of wearing artificial poppies to commemorate the Armistice. She became known in the United States as the Poppy Lady.

The poppy campaign in Canada owes its origins to the French woman Anna Guérin, a formidable force according to historian Heather Anne Johnson in her book, Madame Guérin.

Anna Guérin was instrumental in the poppy campaign in Canada. Poppy pins were first distributed by the Great War Veterans’ Association in November 1921. [Georgia Museum of Art/2018.127]

When Guérin and her first husband moved to the newly established French colony of Madagascar on the east coast of Africa, she established a school for girls. She often rescued women as young as 13 who were raised as slaves and sold in the streets as mistresses to wealthy colonists.

Her first marriage ended in divorce and she married Eugene Guérin, an established jurist who held several positions in French colonies throughout Africa. While he was serving in Africa, she and her two daughters from her first marriage moved to England.

There, Guérin established a second career for herself as a lecturer on famous women from French history, often giving a speech in French and then repeating it immediately in English. These colourful events with magic lantern effects often featured Guérin appearing in costume. Sometimes, she even used an artistic persona named Sarah Granier. (Her mother’s maiden name was Granier.)

When the First World War broke out and much of France was occupied, she refocused her lectures to support French widows and children orphaned by the fighting. Her lectures were so successful that she took them to North America where she toured the United States and Canada to raise funds. The U.S. remained neutral in the war until 1917, so she had to present her lectures as “information sessions” without overt references to fundraising.

“They made wreaths of brilliant red poppies for the graves of overseas soldiers.”

She returned to France after the war, but after touring the former battlefields, she realized there was much to be done for the invalided soldiers. She returned to North America and continued to tour.

Guérin never claimed to have invented the idea of wearing poppies for remembrance. In fact, informal poppy days in Canada had been organized by some chapters of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire.

“It was in the spring of 1919,” wrote the News-Chronicle in Port Arthur, Ont., on July 5, 1921, “while watching the children of devastated France as they made wreaths of brilliant red poppies for the graves of overseas soldiers, that the idea of securing help for the poorly clad orphaned children of destroyed France came to Madame Guérin.”

Guérin was certainly aware of Michael’s campaign and occasionally corresponded with her. Author Johnson maintains that the two women probably saw each other as allies, not rivals.

In 1921, Guérin decided to bring the poppy campaign to the United States and Canada. She was especially interested in Canada, since McCrae was a Canadian. She was in Canada several times speaking to various groups about the proposal.

Canada became the first dominion in the Commonwealth to hold a poppy campaign.

In particular, she addressed the Ladies’ Auxiliary of the Great War Veterans’ Association at its convention in Toronto. With its support, she then presented her proposals to the GWVA executive during its dominion convention in Port Arthur, Ont., in July 1921.

“The GWVA readily accepted the suggestion that the poppy be worn on the anniversary of Armistice Day,” wrote Clifford Bowering in Service: The Story of the Canadian Legion, 1925-1960. “And on Nov. 11, 1921, poppies made by the women and children of France were distributed in Canada for the first time under the sponsorship of the GWVA.”

A member of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League distributes poppy pins. [Legion Magazine Archives]

In doing so, Canada became the first dominion in the Commonwealth to hold a poppy campaign. Later that year, Guérin convinced the British Legion to adopt the poppy campaign. The American Legion held its first poppy campaign before Memorial Day in May 1924.

The GWVA hosted a conference of the British Empire Service League in Ottawa in 1925. There it was decided to accept the poppy as the universal emblem of remembrance throughout the British Empire.

After the first campaign, the GWVA took over, and funds raised stayed in Canada for Canadian veterans.

The original poppy campaign had three purposes: to perpetuate remembrance of the sacrifices made by those who served; to raise money to help veterans in need; and to provide employment for veterans with disabilities.

In 1918, the Canadian Red Cross started a series of workshops in major cities across Canada where veterans were employed in making products such as furniture, picture frames and toys. The enterprise, called Vetcraft Industries Ltd., was later taken over by the federal Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment and became a Crown corporation.

First World War veterans were employed to make poppy pins, wreaths and crosses. [The Royal Canadian Legion; City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 736/The Vimy Foundation]

The GWVA turned to Vetcraft to produce the lapel poppies. As the remembrance period became an annual occurrence, production was expanded to include wreaths and crosses. These items were sold exclusively to the GWVA and its successor, The Royal Canadian Legion.

At its peak, Vetcraft had more than 300 employees, but by 1994 that number had dwindled to about 45 working in two remaining workshops in Toronto and Montreal.

During a government review, it was decided that Vetcraft, now answering to Veterans Affairs Canada, would have to close. The government turned to Dominion Command of the Legion, which did its own study. The Legion looked at possibly manufacturing these items itself but, in the end, decided that production should be handled by a third party, even though this would mean that the work was no longer performed solely by veterans with disabilities.

Dominion Regalia of Toronto took over the manufacturing of poppy materials in 1996. The contract has been tendered several times since. This year, Real Northern Regalia of North York, Ont., took over production.

The annual poppy campaign is launched on the last Friday in October and runs until Nov. 11. The first poppy is presented to the Governor General. The Legion estimates that tens of millions of Canadians wear a poppy during this period. The distribution is handled by volunteers from branches and community groups with the support of many Canadian businesses.

About $18 million is raised each year by the poppy campaign. Poppy funds are kept in poppy trust funds held by individual branches, districts, zones, provincial commands and Dominion Command. The rules for spending the funds are clearly spelled out in the poppy manual published by Legion National Headquarters.

Technology has changed the nature of poppy campaigns over the years. A recent feature of the remembrance period in Ottawa is the Virtual Poppy Drop, in which projected images of poppies cascade down Centre Block on Parliament Hill.

Poppies projected on the Peace Tower mark the remembrance period every November. [Legion Magazine Archives]

A digital poppy was introduced in 2018. It allows people to personalize their messages on social media by including a poppy image.

In 2020, the Legion and HSBC Bank Canada formed a partnership to distribute poppies using “Pay Tribute” tap-enabled donation boxes. As a pilot project, 250 boxes were placed in stores and branches across Ontario. These allow people to donate to the campaign using tap-enabled debit or credit cards. Attractive boxes were designed to resemble the headstone used by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. They include the words from the cenotaph in Halifax: “In honour of those who served, in memory of those who fell.”

This year that trial has been expanded to 1,000 boxes across Canada. “We are also placing them in Canadian Armed Forces bases and wings across Canada,” said Freeman Chute, the Legion’s special projects officer. “There has been a large demand. And the technology has been improved, so now you have a choice of making a $5, $10 or $20 donation with your credit or debit card.”

Another new initiative is the creation of a digital art piece with a remembrance theme. Digital art is the creation of work that is computer-generated, scanned, or drawn using a tablet or mouse. It includes digitally manipulated videos or photographs and is often interactive, allowing the audience to influence the image being created. Many are viewable as a 360-degree piece of art.

The new project for 2021 is called the Immortal Poppy. In a slow-motion video of a poppy blooming, each individual petal will carry the name of one of more than 118,000 individuals who have died while serving in the Canadian Armed Forces.

People can buy a name and save it or sell or trade it in the digital market. “This is new technology but there is quite a market for it,” said Chute.

A century after it started, the poppy campaign is still going strong, just like the tenacious little wildflower that flourished in the fields of Flanders.

—

How is my poppy donation spent?

Poppy funds are collected for the benefit of Canada’s veterans, including members and former members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and their families who are in need.

Funds can be used for:

• grants for food, heating costs, clothes, prescription medicine, appliances and equipment, essential home repairs and emergency shelter

• housing accommodation and care facilities for veterans

• funds for veterans’ transition programs that are directly related to the training, education and support of veterans and their families

• comforts for veterans or their surviving spouses who are hospitalized or in long-term

care facilities

• veterans’ visits, transportation or day trips

• modifications to existing facilities to assist veterans with disabilities

• bursaries for children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of veterans

• support of cadet units

• veterans’ drop-in centres

• community medical appliances, medical training and research which will assists in the care of veterans

• supporting the work of command service officers assisting veterans

• relief of disasters declared by the federal or provincial governments

• administration and promotion of remembrance activities

Advertisement