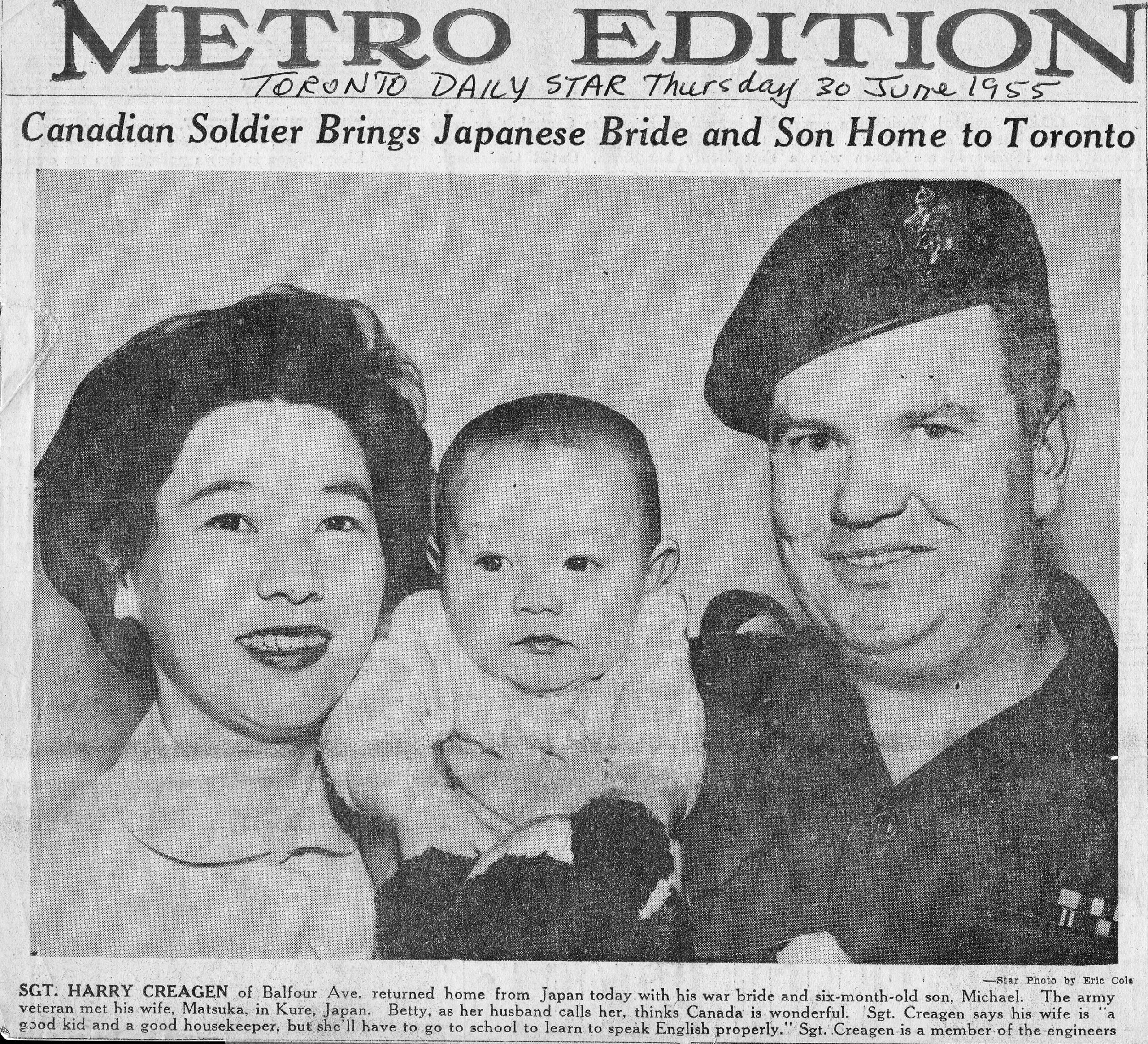

Sergeant Harry Creagen with his bride Matsuko and son Michael on the front of the Toronto Daily Star after arriving at Union Station in Toronto in June 1955. The couple were married for 43 years before the veteran of two wars died in 1997. [Courtesy Michael Creagen]

This story begins with Harry Edward Creagen, a native Irishman who fought with the 35th Battalion, 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles, during the First World War.

He was captured by German forces during the Battle of Sanctuary Wood near Ypres, Belgium, in June 1916. Private Creagen, now a prisoner of war, escaped three times, only to be recaptured each time. After his third getaway, his captors forced him to stand in a rainstorm for 24 hours. It compromised his health for the rest of his days, and Harry Edward Creagen died a young man in 1930.

His son, Harry Elliott Creagen, fared much better by his obstinacy: Against the army’s wishes, the combat engineer married a Japanese woman, Matsuko Mihara (he called her Betty), had two sons and, despite paying for his defiance with a promotion freeze, forged a rewarding life as a sergeant, husband and father.

As a teenager, the oldest of those sons, Japan-born Michael Elliott Creagen, embraced the examples his forebears set for him and resisted authority, starting with his own father’s.

Acting on the advice of that same father, Michael Creagen ventured out into the world and repelled every racist taunt, confronted every inappropriate question about his heritage, and stubbornly—successfully—pursued a career in the highly competitive and monetarily challenging world of freelance photojournalism.

But, throughout his life, it has been the resolute, peaceful obstinacy of his diminutive Japanese mother—all five feet of her—that has been the force and the light that guided him.

She was, as her 2010 obituary described her, “a quiet rebel who defied some Japanese conventions but embraced others in her fiercely independent life.”

A career soldier who fought in Europe and Korea, Harry Creagen respected his enemies. He refused to plunder the bodies of war dead and tried to stop soldiers who did. He retrieved this solitary camouflage German helmet from a field in Holland. It was only after he scampered back to his unit that someone told him he’d just navigated an unmarked minefield. [Michael Creagen]

With peace finally at hand, her mother arranged for Matsuko to marry into a wealthy Japanese family. The union would have ensured prosperity for her family. Matsuko, however, didn’t love the man—she didn’t even like him—and refused to go along with it.

By 1953, the Korean War was at an impasse and Matsuko was working in the British Commonwealth Armed Forces Canteen on the base at Kure, where Sgt. Harry Creagen, a much-travelled Bren gunner raised in Toronto, was stationed for two years after fighting his second war in less than a decade.

The object of her affections came down to a competition between Creagen and an Australian rival. Creagen won out, she said, because she felt safe with him, and he bathed regularly.

The impending marriage faced two obstacles: the army and Matsuko’s widowed mother.

Post-war marriages between Allied forces and local women in both Germany and Japan were frowned upon by Canadian military brass—and legislators.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, some 21,000 Japanese-Canadians had been uprooted from their homes and sent to internment camps for the duration of the Second World War. Most lost everything, and were not released until 1946. The last restrictions on Japanese Canadians weren’t lifted until 1948, when they were granted the right to vote.

But the resentments of that time lingered for years after. A June 1952 cabinet document said the defence minister of the day, First World War veteran Brooke Claxton, was concerned over marriages between Canadians troops and former enemies.

“For a number of reasons it was desirable to discourage such marriages,” said the summary of the day’s cabinet discussions.

“A draft order covering all three services had been prepared which would provide that marriage allowances and transportation for dependants would not be accorded to men in the forces marrying abroad unless the consent of the commanding officer had been given and five months had elapsed from the time of application.”

American and British restrictions were even more stringent, it noted.

Australian Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell had announced in 1948 that no Japanese war brides would be allowed to settle in Australia. “It would be the grossest act of public indecency to permit any Japanese of either sex to pollute Australia” while relatives of dead Australian soldiers were alive, he said.

The edict didn’t last. About 650 Japanese war brides migrated to Australia after the ban was lifted in 1952.

Sgt. Creagen’s commanding officer was unimpressed by Australia’s magnanimity. His reply to Creagen’s request for permission to marry was a flat No. Creagen was summoned to the colonel’s office, where he stood firm in his conviction to marry Matsuko despite threats that his army career would be over if he did.

“One of the things about my family is you don’t tell them they can’t do something they want to do,” said his son in a recent interview. “They’ll just tell you to go fuck yourself.”

An army padre—a Catholic priest—was dispatched to talk some sense into the Protestant Irish-Canadian. The padre knew better.

“What we’re going to do here is we’re going to smoke a cigarette,” he told Creagen, “and when we finish the cigarette, I’m going to go outside and tell them I couldn’t change your mind about this. We’re going to talk about everything but that.”

And that’s what they did.

The soldier and his love had two weddings—a Japanese ceremony in January 1954, and by a military padre 10 months later.

The whole thing didn’t go over too well with Matsuko’s mother, to say the least. Sgt. Creagen was like a ghost in the Mihara family home—unrecognized, unacknowledged, ignored.

“There were still a lot of hard feelings after World War II,” said their elder son, who was born the following December. “So when my mom said she was going to marry a white man, basically she was marrying the enemy. That was just awful.

“When my mom brought my dad over to the house, my grandma would not talk to him, wouldn’t even acknowledge him. I think that’s what all these Japanese women went through who married Canadian soldiers, or married Americans, or whatever.”

Theirs was not the first, nor the last, Canadian-Japanese union to grow out of the post-Korean War postings in Kure. A March 1954 report by the Canadian Military Mission Far East said that as of Jan. 1 of that year marriages between Canadian troops and Japanese women numbered 46. The report said a dozen Japanese brides had been “repatriated” to Canada, while another 22 were in process.

The document noted “several cases of exceptional difficulty,” citing disease, criminal backgrounds and “unusual social problems” among the issues confronting them.

One bride was set to follow her new husband after he had returned to Canada, but when military authorities sought to arrange her passage, they learned she had made off to a remote village with her Japanese lover, “a known gangster and a member of a notorious ring of thugs and hoodlums.” It was believed she was being force-fed heroin, and the report, stamped SECRET, said a rescue operation was planned.

During the pre-approval phase of the marriage process, another couple was found to both have tuberculosis, while a third couple was caught up in an apparent bribery scandal that left the bride high and dry in Japan while her beau was waiting for her back home in Canada.

“This task is becoming increasingly onerous and exacting,” said the mission report. “Dealings with local Japanese authorities are time-consuming and difficult because of the language barrier. The immigration and health clearances required by the Canadian government authorities take many months to complete…”

Yet, while most Japanese brides were sent to Canada aboard ships, the military managed to arrange air transport for one couple so that they would arrive in time to spend the Christmas holiday with the groom’s family.

The coldness with which Matsuko’s mother treated her Canadian son-in-law didn’t thaw until he showed up bearing the newborn Michael—her first grandson—in his arms. According to the story he told his son years later, from then on she would greet Sgt. Creagen with a “how are you” and make off with Baby Michael, pronto.

The three headed for Canada in 1955, making landfall in Vancouver, then crossing the country by train before arriving at Toronto’s Union Station to a celebrity welcome on Thursday, June 30. Their trip took 16 days and ended with stories and pictures in the Toronto Telegram and the Toronto Daily Star.

With typical 1950s’ sensibility, the 32-year-old army sergeant, probably nervous and admittedly “stunned” by the reception, told the enquiring reporters present that his bride was “a good kid and a good housekeeper, but she’ll have to go to school to learn to speak English properly.”

In fact, the shy Matsuko spoke impressive English, according to the Telegram, though she felt she spoke a little fast and was difficult to understand by most anyone but her husband.

Matsuko loved what she had seen of Canada, especially the Rocky Mountains, but she soon learned that there would be challenges that would confront her virtually the rest of her life.

In white-bread Toronto of the day, where mixed-race marriages were almost unheard of and Japanese-Canadians nearly so, Matsuko Creagen was a novelty, and not necessarily a welcome one.

“People would point and stare at my mom whenever she went out,” Michael told Legion Magazine. “They would talk down to her. My dad just didn’t put up with it. He would confront people.”

Her obituary, written by Michael in 2010, said Matsuko “handled it stoically, and she never let it defeat her spirit.” In spite of the obstacles, she found happiness and contentment as a mom and homemaker. She had two sons, Michael, and two years later, Harry Edward.

Taught to cook western-style by an army sergeant who had lived on rations and barracks food, her early culinary attempts were less than stellar—she couldn’t understand why the first chicken she cooked was swimming in grease until she realized it was a duck.

But soon enough, the woman who would come to be known by her four grandkids as Bachan (grandmother), took charge of the kitchen and the household. Her bread rolls, carrot muffins and chocolate chip cookies, known as “Bachan cookies” to the Creagen clan, were famous—her currency among bus drivers, doctors, bankers, neighbours and growing numbers of friends.

“She revelled in her role as mother and homemaker; it was a Japanese tradition she didn’t buck,” Michael said. “It was Mom’s job. We moved every four years and she looked after all the domestic stuff. She built a home everywhere we went.

“She was the boss of the household. What she said was the law.”

She never spoke to either of her sons about racism and never showed either of them any sign of weakness.

Before departing on a visit to her native Japan in 1969, Matsuko Creagen asked her eldest son if there was anything he’d like her to bring him back. He wanted a WW II-era Japanese flag. Unbeknownst to young Michael at the time, his great uncle Toshiro Kiuraki (known as Uncle Joe) was a Japanese navy pilot slated to fly a kamikaze (suicide) mission when the atomic bombs abruptly ended the war. He sent Michael this flag, which had been presented to him by a navy paymaster in anticipation of his last mission. The inscription in old Japanese reads: “Dear Toshiro Kiuraki, Good luck forever on the battlefield. Signed, Katsuhiko Hattori, Paymaster at the Imperial Japanese Navy.” [Michael Creagen]

The couple bought a new home in Collins Bay, outside Kingston, Ont. Harry got a job on Civvy Street running the gymnasium at McArthur Hall at Queen’s University in Kingston. They weren’t rich but, as Michael puts it, “it never felt like we lacked for anything.”

The future photojournalist grew up with passive and overt racism all around him. He was proud of his mixed heritage and once, as a teenager, he asked his father why he didn’t give him at least one Japanese name.

“He said ‘I wanted you guys to fit in, you and your brother.’” With typical irreverence, Michael pulled his eyes into slits and replied: “Ya, I really fit in.”

He would get strange looks from people evidently trying to figure out his heritage. As a four- or five-year-old, another kid called him a “dirty Jap.” Creagen came home crying. His father was having none of it. He sat him down and they had a chat or, more aptly, a lecture.

“You’d better get used to this because you’re going to go through your whole life in this society dealing with this stuff,” he told his son. “Don’t cry. Stand up for yourself. If you show people they can get to you, you’ll be picked on.”

So Michael slugged the next kid who tormented him. The kid never bothered him again. Later in life, he would use his words—blunt and debilitatingly direct. It was the best lesson his father ever taught him. “I’ve been dealing with that stuff my whole life. I never cried about it again.”

At 20, as a summer job interview drew to a close, one of the three federal bureaucrats who had conducted the proceedings asked him: “What are you?”

Michael was dumfounded. “What do you mean?” he asked, knowing full well what the interviewer was asking.

“What are you? Indian? Eskimo? Where do you come from?”

“Is this going to influence whether I get the job?” Creagen replied as the other two interviewers sank into their chairs. It was 1976.

“No, no,” said the now-retreating bureaucrat. “I’m just curious.”

Michael Creagen got the job.

He appreciated the fact grade-school teachers would encourage him to do projects on his Japanese heritage. Once in Grade 4, he came to school in a kimono for a school heritage day.

His dad had a passion for First World War aircraft, developed a reputation as a consummate researcher and sometime writer, and was a founding member of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, Membership No. 004.

The burly Irishman died in 1997 after a long bout with Alzheimer’s. He left behind a library of 1,200 books on First World War aviation and related militaria, along with volumes of research that went to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa.

“Both my parents defied authority,” Michael said. “They went against the grain. They taught by example. When I was 12, I realized my dad was an authority, and I was going to defy him.”

Michael taught his two daughters the same thing—and got the same back.

And so it went.

Advertisement