German soldiers march in Belgium in 1940.[Ra Roe/Wikipedia]

Maurice Van Landschoot was only 14 when the Germans arrived. The young Belgian’s world was turned upside down when his country capitulated just 18 days after the Nazis invaded the Low Countries and France in May 1940.

For the Van Landschoot family, a long-established Belgian clan with roots in the region dating back to the Crusades, living under German occupation offered little prospects for hope. Their prosperous farm, near Adegem, was just a few kilometres from the newly established Flugplatz Maldegem, a Luftwaffe airfield.

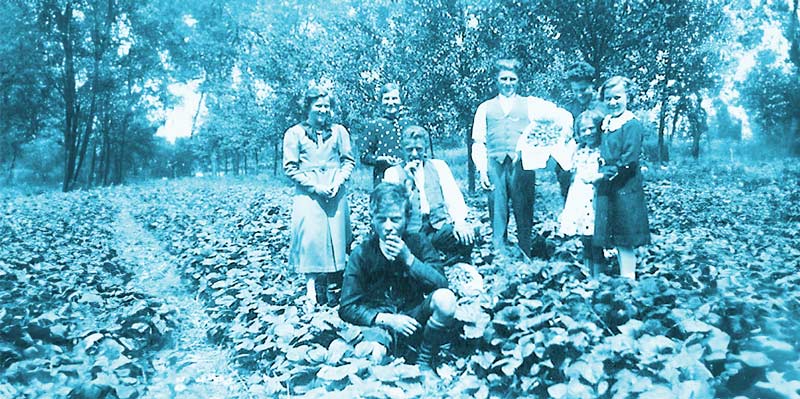

The Van Landschoot family picks strawberries to sell to the invaders and works grain fields on their farm.[Courtesy Van Landschoot family]

It didn’t take long for the occupiers to help themselves to whatever they wanted in this abundant agricultural area, including the Van Landschoot’s horses and cows. The airbase, however, needed a regular supply of fresh food and, so, the Van Landschoot’s were permitted to keep two of their horses to work the land.

It was Maurice’s job to deliver produce, bread and other foodstuffs to the Germans. Soon, the red-headed kid became a familiar face around the base and some of Luftwaffe personnel even considered the young Belgian a friend.

The Van Landschoot family picks strawberries to sell to the invaders and works grain fields on their farm.[Courtesy Van Landschoot family]

Little did they know how much Maurice despised them. He hated how they treated his parents and stole their food and livestock. Over time, the teen found ways to resist. During the next four years, Maurice embarked on a covert and increasingly dangerous life that included acts of sabotage.

During his routine deliveries to the airfield, Maurice began tampering with the planes. He would partially disconnect their fuel lines so that once airborne, the engine’s vibration would cause them to detach completely, thereby bringing the aircraft down.

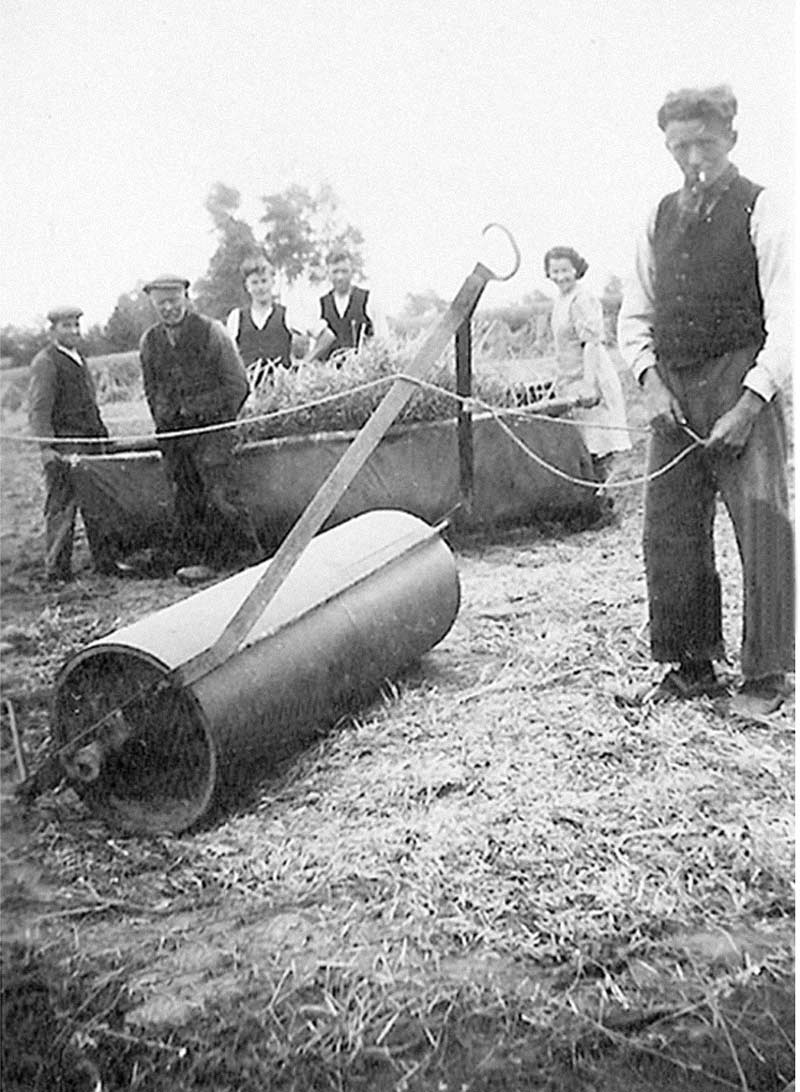

Maurice Van Landschoot (right, opposite bottom) and other local boys harvest land near the WW II Luftwaffe airfield.[Courtesy Van Landschoot family]

Maurice’s resistance didn’t just take the form of sabotage. He also shared intel with the Allies using a radio transmitter that he kept hidden under the floorboards of the family barn. Maurice’s secret identity code was “151,” which he tapped out on the transmitter before sending information to London. If he needed to move the unit, he concealed it in a small case his younger sister would carry. The Germans never suspected anything as the little girl walked among them. The soldiers just thought she was carrying books to school.

Maurice also shared intel with the Allies using a radio transmitter that he kept hidden under the floorboards of the family barn.

Maurice also hid people from the dreaded Gestapo. It was a dangerous existence. By the spring of 1944, the Germans were growing suspicious of the now 18-year-old’s activities. It seemed only a matter of time before they would uncover the truth. And, when they did, it would be a matter of life or death.

Maurice’s chances of survival improved greatly, however, after the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944. By mid-September, Canadian and Polish troops had liberated the Adegem area. For the Van Landschoot’s and their neighbours in east Flanders, the occupation was over.

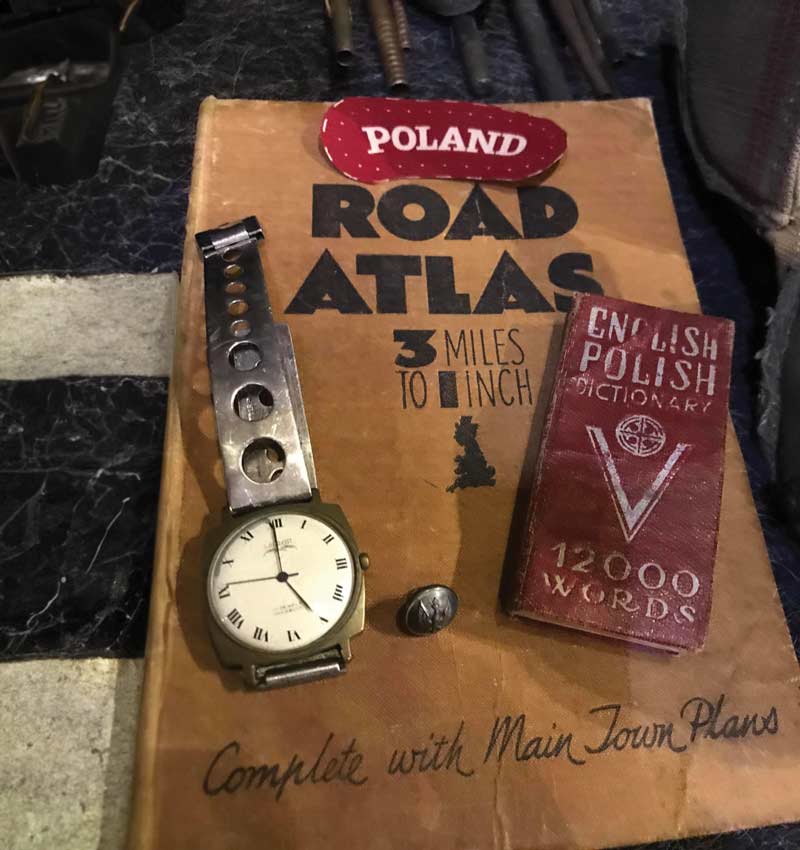

The transmitter Maurice used to share intel with the Allies. [Courtesy Van Landschoot family]

But not everyone in the community welcomed the liberators. Some had collaborated with the Nazis and even prospered under them. Maurice, fearing retribution from some revenge-seeking Nazi sympathizer, remained silent about his wartime activities; even his own family wouldn’t know about his clandestine role for more than 40 years.

In 1987, a dying Maurice finally revealed his long-held secret to his son Gilbert. Before he passed, Maurice made Gilbert promise to do something to honour and remember the Canadians and Poles who had liberated their part of Belgium and to whom he surely owed his life. Said the father to his boy: “If once somebody has helped you out, you’ve got to do something in return.”

His younger sister helped conceal it in various locations. [Courtesy Van Landschoot family]

On the anniversary of the area’s liberation the year after his dad’s death, Gilbert brought flowers to the nearby Adegem Canadian War Cemetery. Gilbert felt, however, he needed to do much more to fulfil his vow to his father. With the 50th anniversary of the liberation approaching in 1994, the time seemed ideal to honour those who saved his father and set his beloved homeland free.

Not everyone shared in Gilbert’s enthusiasm for a commemoration. Local politicians dithered and the community debated how, and even if, the liberation should be recognized. Some weren’t keen to recall the war; those who had collaborated with the Nazis, and their descendants, didn’t want to revive those memories. Gilbert attended public meetings and soon realized there was no consensus and, that likely, nothing would be done.

Undeterred, Gilbert had his own plan: he envisioned a museum dedicated to the Canadians and Poles so that younger generations would know what was done for them. He bypassed the politicians and the bureaucrats and appealed directly to the citizens of east Flanders. Did they not remember the many relationships that developed between Belgian women and their Canadian “loverboys” or the soldiers who subsequently became known as “water rats” for fighting across the soggy Scheldt landscape?

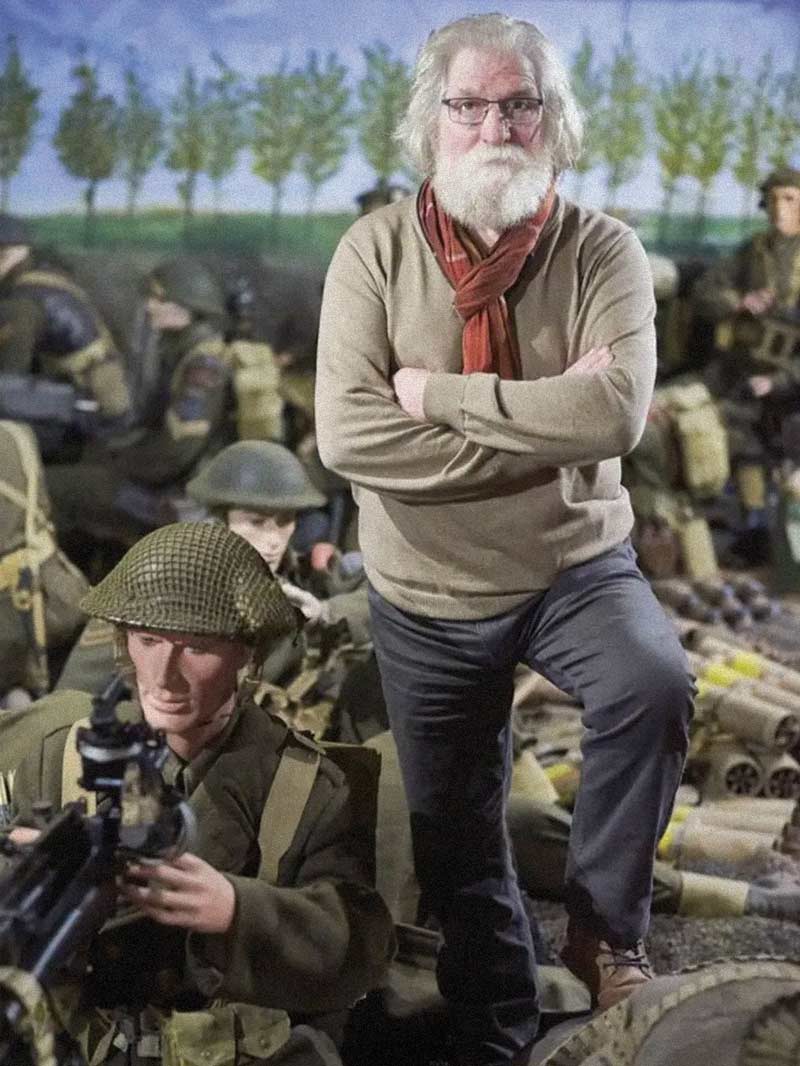

Gilbert Van Landschoot stands amid a display in the Canada Poland War II Museum he built to honour his father Maurice. [Courtesy Van Landschoot family]

The response from locals was overwhelming. Many had artifacts from the war—uniforms, equipment, weapons—in their attics, basements and garages. Items of every description, from Canadian issue toothbrushes to Bren gun carriers, soon materialized. Gilbert, along with a handful of helpers, started work on the building in late May 1995 on the grounds of his parents’ farm.

They worked day and night and completed the Canada Poland War II Museum, from groundbreaking to grand opening with full displays, in just 34 days. The king and queen of Belgium were the first visitors.

They, like all guests, encountered a breathtaking array of Christian symbolism, beauty and history that binds the family’s Crusader origins to the wartime fighters from Canada and Poland.

The facility’s foyer is dominated by four massive stained-glass windows that feature Canadian, Polish and Belgian heraldic and regimental crests. Just past them is a large great room, where a huge column in the middle supports two cross beams, their intersection forming a cross. The ceiling’s four quadrants represent the four seasons, and its main beam runs the room’s length and is touted as the largest oak beam in the world.

The museum boasts one of the best collections of military memorabilia anywhere.

Further subdividing the ceiling are 52 cross beams, one for each week in a year. These sections are split further by 366 smaller beams, equal to the number of days in 1944, the leap year the area was liberated. Supporting all this are 12 freestone pillars representing the 12 apostles, as well as the 12 months of the year. Three larger round pillars symbolize the Holy Trinity.

The great room’s bar, meanwhile, features ironwork from the former communion table of a long destroyed medieval church, while the pillars behind the counter are from its loft. The room also serves as a studio where locals gather and where Gilbert’s daughter, Alexandra, operates a dance school. The dance floor was a deliberate homage to the lover boys who wooed the local girls.

Then there’s the museum proper, boasting one of the best collections of military memorabilia anywhere. More than 370 authentically dressed mannequins feature in the facility’s diorama displays. Gilbert’s attention to detail, right down to the hobnails and spent shell casings, is apparent throughout. Visitors walk through a timeline of the area’s wartime history, from the heroic but ill-fated Belgian defense in 1940, through the dark years of Nazi occupation, to the arrival of the Canadians and Poles in 1944.

Some of the artifacts are so rare that major museums around the world have offered staggering sums to purchase them. “But,” says Gilbert, “they are not sale.” He prides himself on the fact that not one euro of government money has ever funded his collection.

Gilbert’s institution was the result of his determination to fulfil a death-bed promise to his father. It preserves the memory of those who came from far away to fight for Belgium. “New generations come to learn that many soldiers died for the peace and freedom for their future,” said Alexandra.

The museum, now nearing 30 years of operation, is surely a tribute to Gilbert, too. He has honoured his vow to do something in return.

The Van Landschoot’s collection of Second World War artifacts includes many items so rare that major museums around the world offer staggering sums to purchase them. It also boasts a series of detailed battlefield dioramas. [Canada Poland War II Museum]

The Van Landschoot’s collection of Second World War artifacts includes many items so rare that major museums around the world offer staggering sums to purchase them. It also boasts a series of detailed battlefield dioramas. [Canada Poland War II Museum]

The Van Landschoot’s collection of Second World War artifacts includes many items so rare that major museums around the world offer staggering sums to purchase them. It also boasts a series of detailed battlefield dioramas. [ Aaron Kylie/LM]

Advertisement