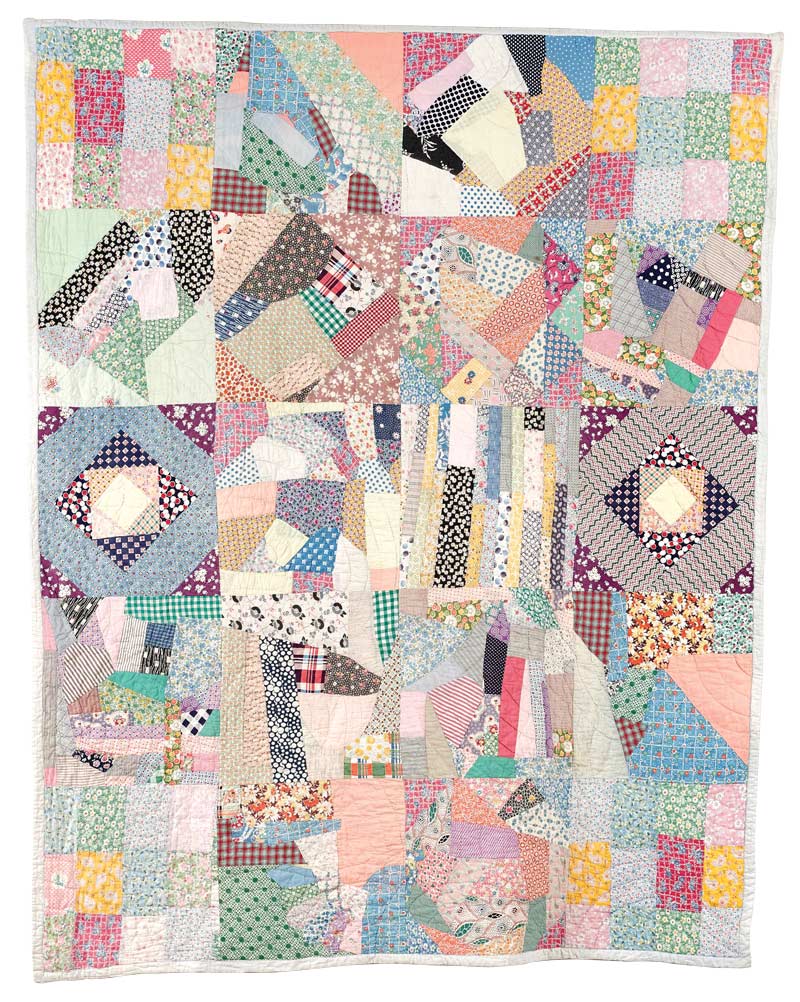

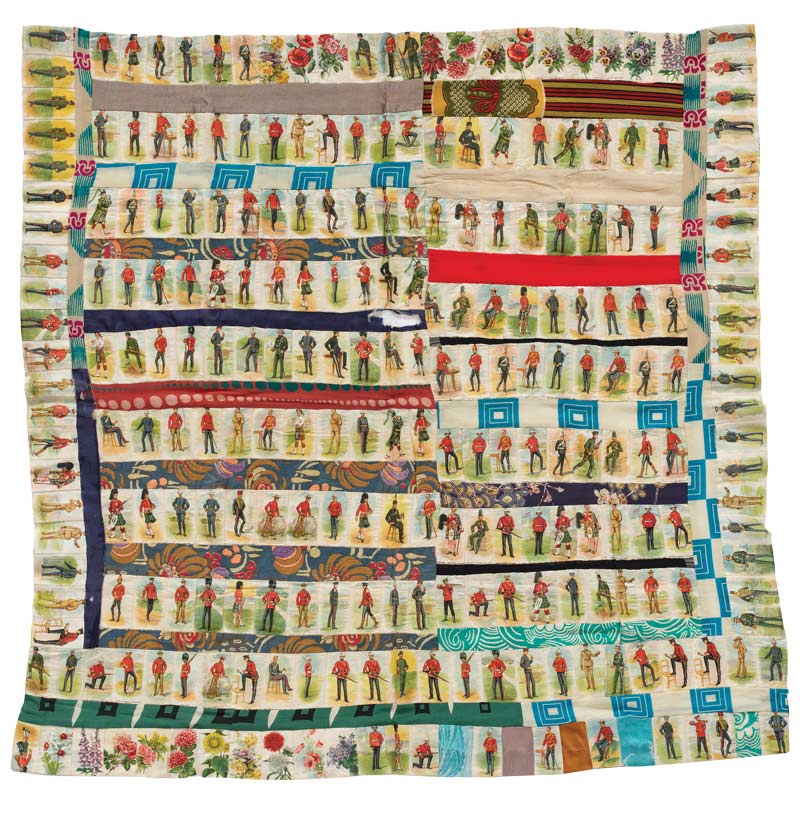

Canadian-made WW II-era quilts, the so-called “Crazy Patchwork Canadian Red Cross Quilt” [The Quilt Collection/Bill Richard]

Through hushed voices, stooped shoulders, bent heads and labouring hands, the women quietly fought. They gathered in Alberta farmhouses, Ontario church halls and Maritime libraries, their weapons of choice that of needle, thread and fabric.

A dozen crafters—some older, others younger—maintained focus as the more experienced stitchers, those with skills born of Depression-era necessity or passed down generationally, offered guidance to amateurs, their apprentices-in-all-but-name.

The patchwork forum was a safe space to improve, yes; where abilities may be honed to form a quilt’s three layers, from top to backing to its middle batting—what those poor bombed-out Britons for whom the bedcovering was made, tended to call wadding.

But the congregation’s role, its purpose, went far beyond a makeshift classroom.

Here, in the company of home front do-gooders, of Red Cross volunteers, Ladies’ Auxiliary members and Women’s Institute supporters, there existed community, itself the product of a common goal: Bringing comfort and care to the war’s weariest.

This is the story of those quilt makers.

Sewn into the fabric of nationhood is Canada’s quilting history, explained expert researcher, author, military veteran and quilt maker Pam Robertson Rivet. “There are some great examples [of quilts] throughout much of the 19th century, but the Confederation Quilt is particularly special. It was made by Fannie Parlee, who used fabric from dresses worn at formal events during the 1864 Charlottetown Conference.”

Canadian-made WW II-era quilts, the so-called “Crazy Patchwork Hallville Canadian Red Cross Quilt [The Quilt Collection]

While quilting trends fluctuated during the succeeding years and decades, it returned in full swing after the outbreak of the First World War. The privations of life in the trenches galvanized Canadian women and girls like never before, their collective efforts bolstered by the still-fledgling Canadian Red Cross—legally established in 1909.

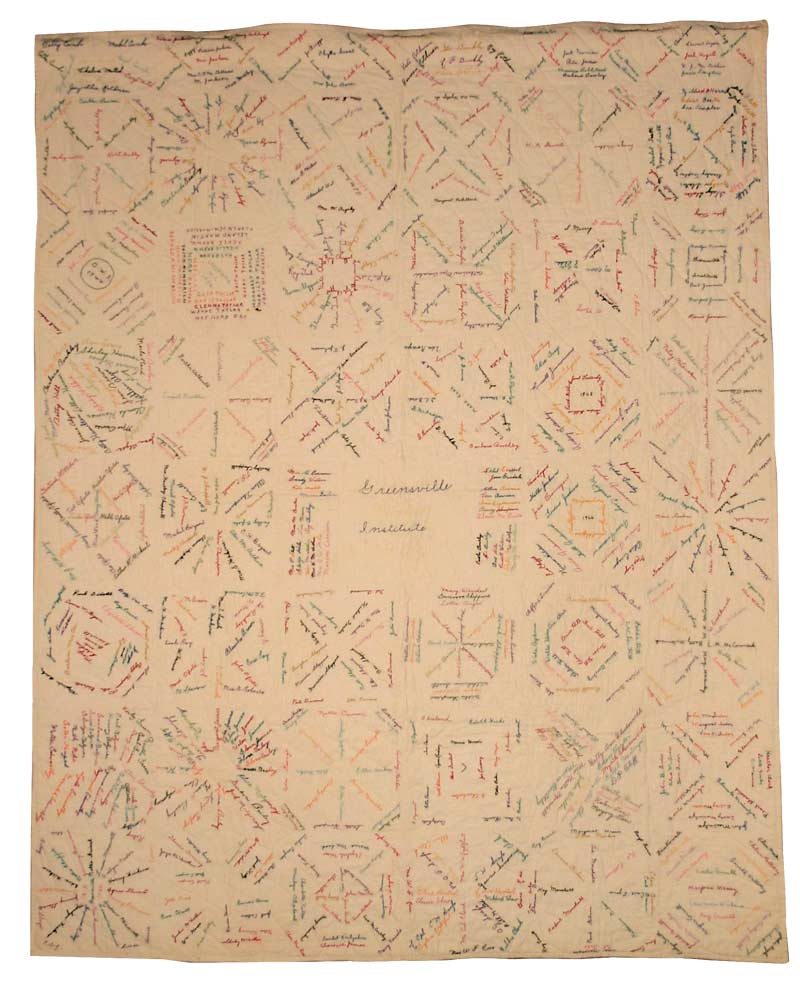

“The First World War was a time for fundraising quilts,” said Rivet. “Of those, the most popular were probably signature quilts, where people would pay a few cents to have their names embroidered into the fabric. Once complete, they were raffled off to raise additional money [for the war effort] in which $1,000 could outfit 126 hospital beds with sheets and blankets or support in organizing a field ambulance.”

Beyond crafting quilts, volunteers produced socks, sweaters, and “miles and miles” of bandages. Equally, patriotism could manifest itself in the canning of preserves and preparing care packages for soldiers, sailors and airmen fighting overseas.

By the 1930s, however, the Great Depression ensured that charity began at home. Crafters continued to form social circles for many important tasks, keeping fabric scraps from Eaton’s catalogues and recycling any and all cloth leftovers. Though impractical for earning money, quilting was a frugal option in household warmth.

It was a make-do-and-mend mentality destined to endure, indeed amplify, into the Second World War, when “women were getting themselves organized before the conflict had even been declared,” said Rivet. “It was evident that they knew what was coming.”

Ontario’s Greensville Women’s Institute created this signature quilt as a fundraiser in 1944. Individuals paid 50 cents each to have their names embroidered on it.[Dundas Museum & Archives/1973.001]

A seismic shift in societal expectations for Canadian women dawned on Sept. 10, 1939, expanding exponentially during the following six years. In the preceding peacetime, nearly 600,000 women—out of a nationwide population of 11 million—held jobs. By 1945, 1.2 million female volunteers had served king and country, be it through the tens of thousands working in war industry, the 4,480 enlisted as nursing sisters, or the broader 50,000 in the armed forces.

Gender norms were turned on their head. Nevertheless, there remained an ever-critical place in the Allied war effort for traditionally female homemakers, from planting victory gardens to salvaging metal for collection drives. Civilian women prepared parcels for troops overseas. They supported displaced people by donating clothing and helping to establish refugee centres. Investing in war bonds, creating non-perishable foodstuffs and volunteering labour all became standard practices, mirroring similar acts of the Great War.

This is the story of those quilt makers.

Also as before, women wielded knitting needles and sewing machines, fashioning upward of 50 million comfort items, including mitts, scarves, balaclavas, socks, slippers, pyjamas and more, as well as wartime essentials, including uniforms and surgical face masks. The Canadian Red Cross again played a leading role in orchestrating efforts, tasked with prioritizing humanitarian aid for those in the direst need of it.

By the fall of 1940, as the German Luftwaffe rained hell on London and other British cities, that aid was primarily directed toward civilian victims of the Blitz. For Canada’s quilt makers, news of destitute families devoid of most possessions became a call to action. Organizations, including the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire and various local women’s groups, mustered their members.

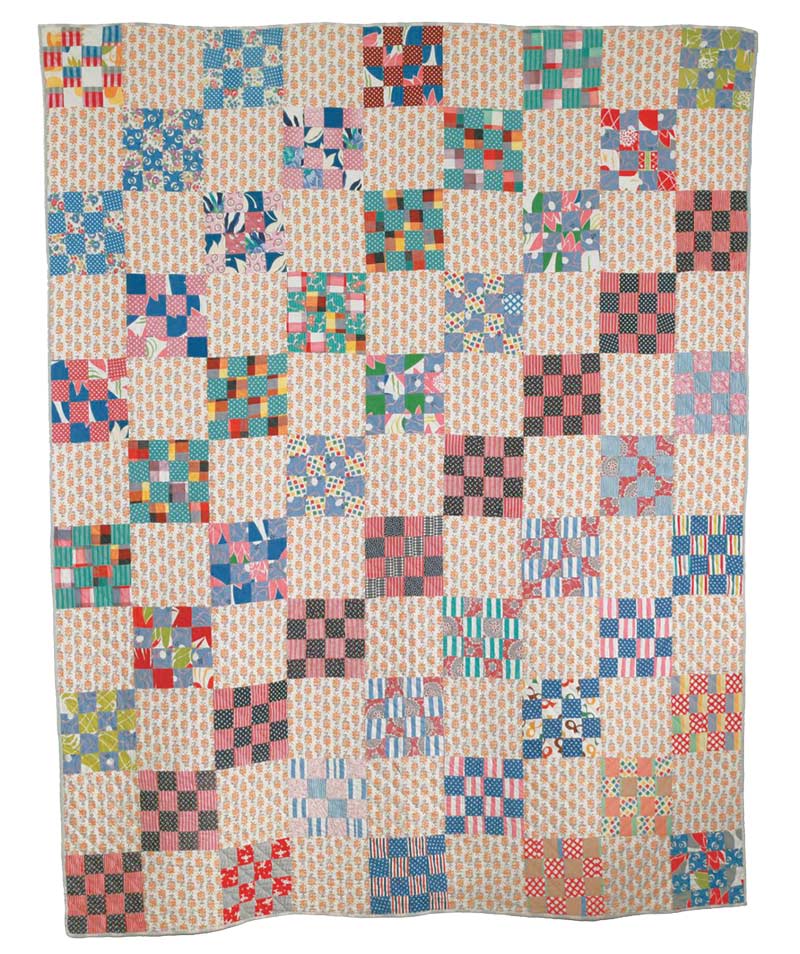

“They were often getting together in homes and community halls,” noted Rivet. “Patchwork was being done, which is essentially combining squares of new or leftover fabric, but there are many other types of quilts made during the period.

“Whole-cloth quilts were one such type, made from one large piece of fabric or sometimes two sewn together. There were a lot of crazy quilts done in a similar style to the Confederation Quilt; people think these were just randomly placed scraps, but they were actually intentionally made with a great deal of thought.”

Despite this, it was quantity, not always quality, required by the Canadian Red Cross, meaning that a sizable proportion of quilts were decidedly utilitarian in appearance. Rationing’s impact on clothing shortages, combined with the Red Cross’s own limited supplies, resulted in most volunteers having to improvise.

Offcuts from garment manufacturers, remnants of worn-out clothes and leftover “orphan blocks” from completed quilts were incorporated into new patterns.

Textile constraints aside, plenty were as visually striking as they were practical.

A certain degree of uniformity came in labels attached to each quilt reading “Gift of the Canadian Red Cross Society,” with personal notes identifying place names, groups or individuals discouraged. “But that wasn’t always the case,” said Rivet.

“Every once in a while, the more rebellious women might embroider the name of their town or organization into the quilt itself. Others even snuck in messages that contained their own names and addresses. There appears to be some resistance in being told what to do in terms of how, exactly, they could support the war effort.”

In a sense, however, the women were just as much helping themselves.

“Their husbands were gone,” Rivet continued. “Their sons, neighbours and loved ones were gone, some never to return. Many women had few other people to talk to, so quilting bees, or sewing days, could offer them a community of belonging.”

Grief-stricken volunteers, bearing the tragic news of loss overseas, could, if they so chose, seek solace in fellow quilt makers. “Occasionally,” Rivet suggested, “sitting in melancholy can be comfort in itself. So, if you’re in a community that shares those feelings, it can sometimes be a better way, at least for certain people, to process it.”

Their collective commitment, meanwhile, was resolute from province to province. Records lack consistency, but widely referenced figures indicate that Nova Scotians contributed roughly 25,000 quilts between 1941 and 1945; Albertans’ total output topped 43,000; and Saskatchewanians supplied 50,000. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the greatest producer was densely populated Ontario, with donations hitting the hundreds of thousands.

Collected by the Red Cross, they would find homes with those experiencing homelessness.

Alice Amy Treeby, a young resident of the English village of Strete, remembered the day she was ordered to leave. It was, she wrote, the second week of November 1943, and “we were given notice to quit our homes and farms within six weeks to make way for military training of American troops” ahead of D-Day preparations.

The entire Treeby family resettled for 11 months before being permitted to return. For their troubles, they received five Canadian Red Cross quilts, one a 16-block patchwork crafted from dress cottons and rayons, backed with pyjama material or striped flannelette, and adorned with what appear to be Spitfire motifs.

The following year in the same west coast English county, Bill Richard was vacationing with his mother, sister and neighbours when they learned their home in the town of Bexley had been destroyed. The Richards, too, received quilts, one consisting of spotted, striped and floral-patterned strips, mostly rayons.

One of the five Canadian Red Cross quilts Briton Alice Amy Treeby’s family received late in WW II. [The Quilt Collection/Alice Amy Treeby]

“The quilt stayed on my bed for years and then on my children’s bed,” he wrote.

Maureen Hill of London recalled her father fixing a ceiling light when a V-2 landed on the house next door. Her parents became the recipients of a double quilt and she a single—both donations from the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire. In the corner of one, “Mrs. J. A. McCowan” of Summerberry, Sask., identified herself as the creator.

Across much of the country, wherever Britons had lost their belongings, Canadian quilts brought warmth from afar. Having journeyed over the Atlantic as part of the Allied convoys, most spreads were distributed by the Women’s Voluntary Service, aided by welfare organizations such as the Salvation Army and the British Red Cross.

Quilts arrived at English orphanages, Belgian field hospitals and Dutch refugee centres. They were wrapped around the shoulders of convalescing Canadians in London and spread over the laps of dust-covered civilians after bombing raids.

Not only did quilts offer warmth, but they also animated spirits with their abundance of colour. One Canadian in Britain described an underground shelter where he saw countless civilians swaddled in patchwork: “I came to call them Canadian flower beds…very bright and homelike they seemed to me.”

Similarly, A. Shannon of Allied Forces HQ in Europe recorded: “Never in all my war service have I known any comforts give more pleasure.”

Even the Queen took note, remarking in an audience with a Canadian chairperson at war’s end: “Please tell the women of Canada how deeply touched I am by all they have done for us.”

An estimated 400,000 quilts passed through the hands of Canadian women and girls, as well as a scattering of men and boys, bound for European civilians and Allied service personnel during the Second World War. Calculations by textile expert Joanna Dermenjian allude to approximately 50 hours of committed crafting per quilt—or a minimum of 20 million work hours for the entire feat.

Canada’s handmade spreads remained treasured possessions for an untold number of households, many of which were passed down through the generations like the very skills that made them possible. Over the decades, however, moth-eaten quilts began to fray, their patches never repaired. Others were misplaced and forgotten.

“Never in all my war service have I known any comforts give more pleasure.”

So, too, were their respective histories and creators, noted Rivet: “It’s no secret that volunteer organizations aren’t typically the place to be if people want recognition. That was sometimes, if not always, the case for the quilt makers in World War II.”

In 2005, the Canadian Red Cross Quilt Research Group, itself an offshoot of the British Quilt Study Group, was founded to help raise the profile of the Canadian volunteers and, above all else, to repatriate their surviving bedspreads to Canada.

Though no definitive figure exists, it has been suggested that between 200 and 300 quilts remain on both sides of the Atlantic. Of these, dozens have since returned to Canadian soil despite challenges in finding a museum to host the entire collection. The group has instead approached local institutions to maintain individual quilts.

Nestled in darkened closet corners, stowed beneath unused beds, tucked away in dusty attic spaces and perhaps hidden in plain sight—displayed in a second-hand shop window, showcased as an heirloom of unknown origins, or balanced on a loved one’s favourite armchair—are undoubtedly, unquestionably, more, their aging yet sturdy fabric a testament to resilience, their stories a thread to pull.

Patchwork spirit

The woven tales of three quilt makers and their poignant exploits

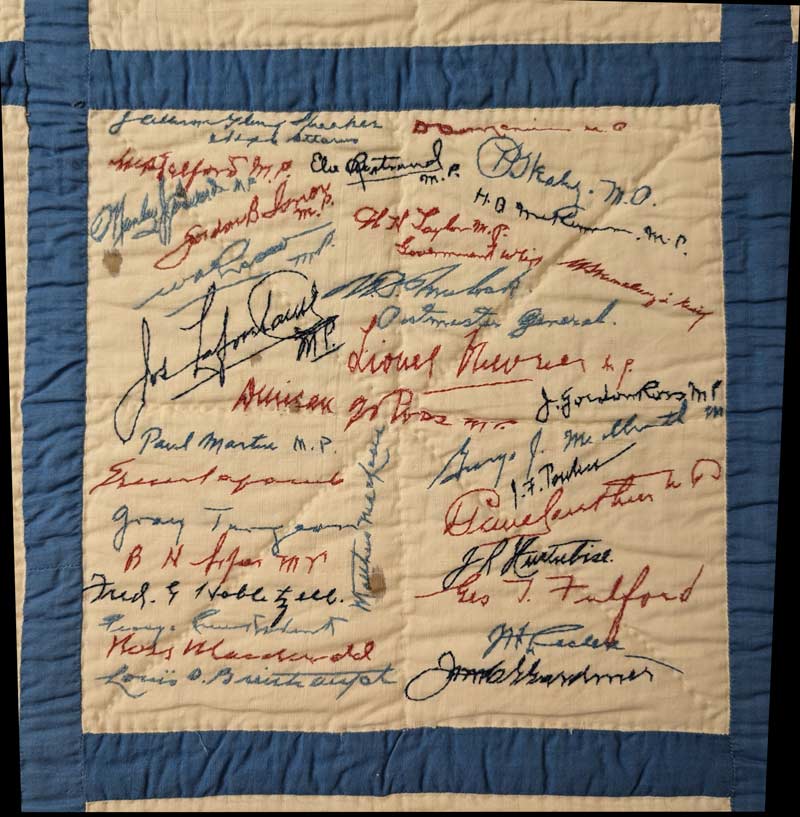

Margaret Eaton Bishop, wife of Canadian airman and Great War Victoria Cross recipient Billy Bishop, found a different way to galvanize quilt makers. Though a venture replicated elsewhere, she capitalized on her husband’s transatlantic travel plans by having him collect signatures to later embroider into a fundraising quilt.

Their joint efforts at home and abroad—part of a larger initiative by air force officers’ wives in Ottawa—produced 1,000 autographs, including at least 100 of renowned figures such as Walt Disney, Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Mackenzie King and Winston Churchill. Consisting of 67 white squares and framed by a light-blue border, the spread—crafted by nuns of the Shepherds of Good Hope in Ottawa—was fittingly dubbed the “Famous Names” quilt.

It next embarked on a nationwide tour where Canadians purchased raffle tickets at 25 cents—or five for a dollar—to have a chance of winning the bedcovering. The scheme raised $12,000 (more than $274,000 in 2025), with the quilt presented to a Mrs. K. Molt-Wengel of Pointe du Bois, Man., in 1943, who hosted home showings to raise further war funds. It resides today at the C2 Centre for Craft in Winnipeg.

Kinu Murakami of Vancouver, meanwhile, was a dressmaker of Japanese origin whose experiences couldn’t have been starker. Having immigrated to Canada in 1907, she, her entire family and some 21,000 other Japanese-Canadians were forcibly relocated from the West Coast to inland internment camps, deprived of most property and belongings, and framed as enemy aliens during WW II.

Murakami was first exiled to Kaslo, B.C., but was subsequently transferred to the provincial incarceration centre in New Denver. Though little is known about her experiences, it’s likely that she began quilting around the time of her internment.

The bulk of Murakami’s block design comprises 247 so-called silks from cigarette packets, a corporate marketing strategy that attempted to promote smoking among women. Technically made from cotton and silk blend patches, 225 of these inserts depict Canadian regimental uniforms, unintentionally imbuing the quilt top with irony that perhaps wasn’t lost on its maker. The remainder of the spread includes fragments of Japanese kimonos, a testament to resilience during one of Canada’s darkest chapters. Murakami’s quilt is in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

[Manitoba Crafts Museum and Library]

[Royal Ontario Museum]

Ethel Rogers Mulvany of Manitoulin Island, Ont., showed resilience of her own when the British colony of Singapore fell to Japanese forces on Feb. 15, 1942. An Australian Red Cross ambulance driver in the Crown territory, she and her British husband Denis, a doctor, were among thousands of Allied civilians taken prisoner.

Their Japanese captors separated the men from women and children with almost no means to communicate. Mulvany, however, devised a plan in which she and other female internees at Changi Prison could inform male loved ones that they were alive.

The women received permission from Japanese authorities to create quilts for the men in hospital. Spearheaded by Mulvany, prisoners embroidered their signatures and personalized imagery onto patches of white cloth and empty rice sacks. Each patchwork contained 66 squares, within which were subtle messages to recipients.

Australian internee Ossie Hancock stitched a “V,” presumably for victory, beside two rabbits, a possible reference to her two daughters for her incarcerated husband. British nurse Mary Buckley, meanwhile, portrayed Welsh symbols, writing “Cymru am byth” (Wales forever). Trudie van Roode, a Dutch teacher, chose to encapsulate the mood of innumerable prisoners by displaying a table laid with a banquet next to the words, “It was only a dream.” Mulvany, aided by comrade Margaret Burns, worked two maple leaves into her square, embroidering “Canada” as a final note.

Two Changi quilts are part of the Australian War Memorial collection in Canberra. A third resides at the British Red Cross Museum and Archives in London.

Bishop and Mulvany survived the war. Murakami died in New Denver in 1947.

Advertisement