Illustration by Kerry Hodgson

Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmondson took it as long as she could.

Born in December 1841 in the small farming community of Magaguadavic, about 60 kilometres southwest of Fredericton, Emma was the youngest of four girls and an epileptic boy. When she arrived, her father Isaac resented the fact she was not a healthy male who could help on the farm.

Despite excelling at everything she could to prove she was as good as a boy—riding, shooting, swimming—it still was not enough for her dad. With limited opportunities, Emma had undoubtedly reconciled herself to the lot of a typical mid-19th century woman: early marriage, followed by a lifetime of household labour.

When she first read of Fanny’s adventures, she felt as if an angel had touched her with a live coal.

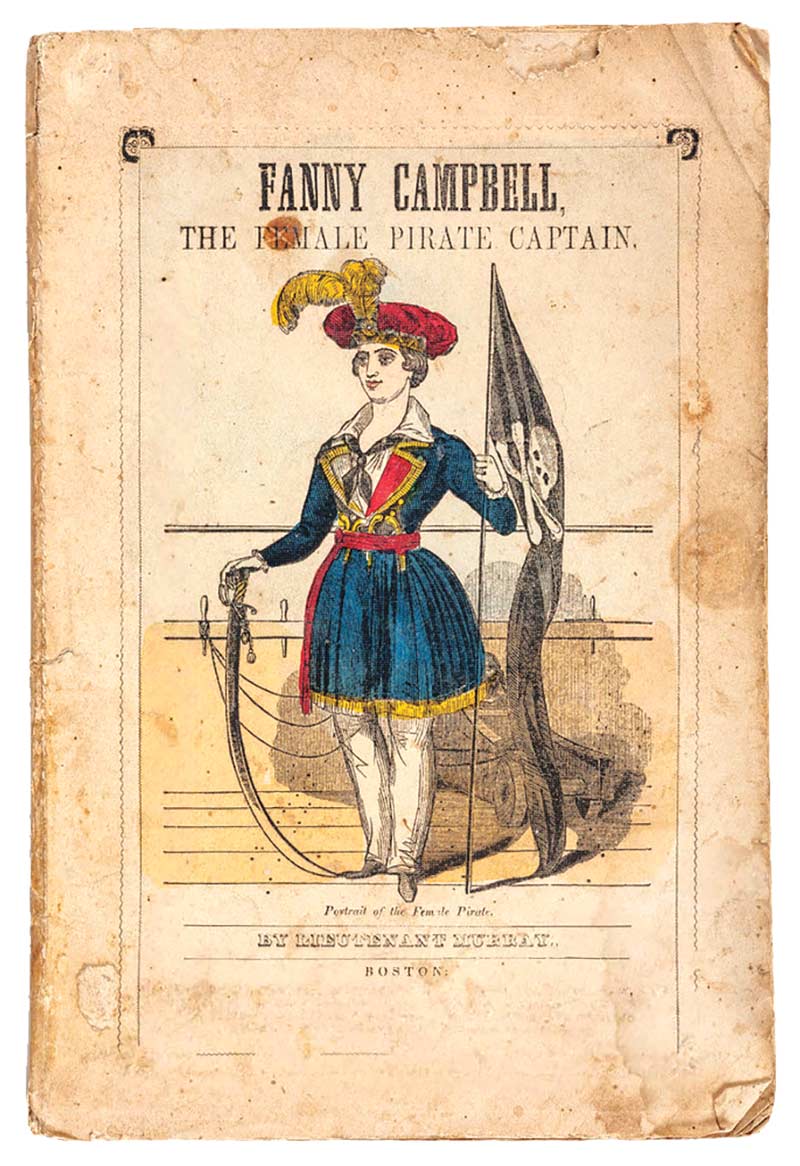

Then a book she received from a passing peddler when she was nine years old changed everything. It was the 1844 novel Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain. In it, Fanny disguises herself as a man to rescue her lover. She does so by the simple expedient of cutting off her brown curls and donning men’s clothing.

The realization that such a possibility was also open to her hit Emma like a freight train. After surreptitiously reading the book (when she should have been planting potatoes), her one goal was to achieve the independence Fanny had. As she later wrote, when she first read of Fanny’s adventures, she felt as if an angel had touched her with a live coal.

When she was 15, Emma’s father arranged her marriage to an older man. The prospect upset her so much that, assisted by a family friend, she ran away. She changed her last name to Edmonds and eventually ended up as the co-owner of a millinery shop in Moncton, N.B.

When her father discovered her whereabouts, Emma quickly packed up and moved to Saint John, N.B. Once in the port city, she disappeared and emerged as a new person. Emma cut her hair short, tanned her face with stain and wore men’s suits. And she changed her name again.

As Franklin (Frank) Thompson, Emma got a job as a travelling salesman peddling Bibles door to door. Her employer later stated that in 30 years, none of his men sold more Bibles than Frank. In 1860, Emma moved to Flint, Mich., where she continued to sell Bibles.

In May 1861, a month after Confederate forces started the American Civil War by firing on Fort Sumter, Franklin Thompson enlisted in the Union Army, swept up in a spirit of patriotism toward her new country. She joined Company ‘F’, 2nd Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Medical examinations were cursory in those days, consisting only of a few questions and rarely requiring the prospective recruit to remove any clothing. Due to her small stature (five feet, six inches) Frank became a “male” field nurse. Thousands of other recruits were smooth-faced boys wearing ill-fitting uniforms, so Emma had no difficulty fitting in.

She was also helped by the male modesty standards of the time. In the field, soldiers slept fully clothed and bathed in their underwear. Whenever they could, they bypassed smelly open pit latrines for a private spot in any nearby woods. Emma did likewise.

After training, Emma’s unit was sent to Virginia to join Major-General George McClellan’s campaign. She was assigned to a hospital unit. Before McClellan could attack, however, he needed a spy to go behind Confederate lines and replace a Union agent who was executed by the rebels. Emma volunteered.

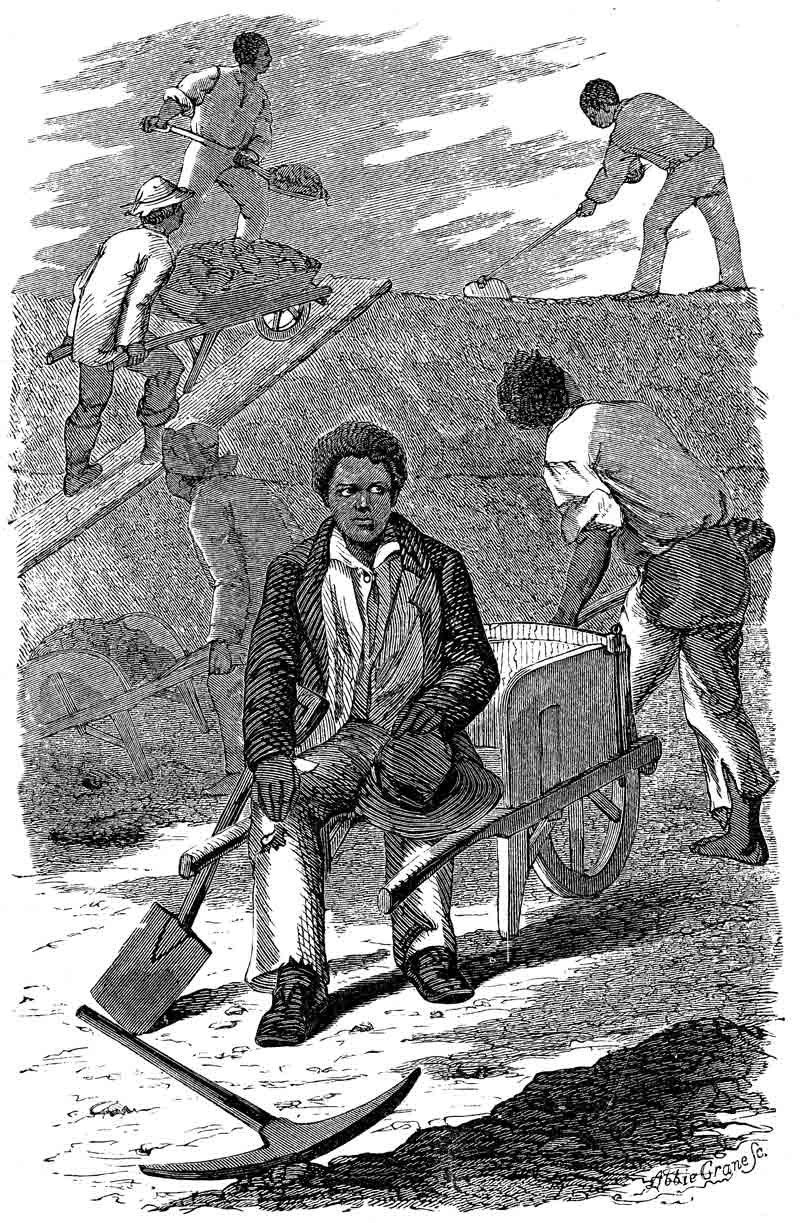

To avoid suspicion, Emma disguised herself as a Black man. She darkened her skin with silver nitrate and wore a curly black wig. When she arrived behind the rebel front, she was put to work with other Blacks digging defences for the expected Union assault. After the first day, Emma’s hands were so badly blistered that she was able to change jobs and get work in a kitchen.

Emma kept her eyes and ears open and learned much valuable information about the Confederates. After her second day, she was given picket duty, which allowed her to escape and return to the Union side. Emma brought back crucial details about Confederate morale, numbers, weapons and plans. Then she returned to her duties as a male nurse.

As a youngster, Emma read the 1844 novel Fanny Campbell, The Female Pirate Captain, which influenced her greatly. [Fanny Campbell, The Female Pirate Captain;]

Two months later, Emma was again ordered to infiltrate the rebel lines. This time, she posed as a fat Irish peddler woman. She once more brought back valuable intelligence to the Union Army.

By this time, the 2nd Michigan was transferred to the Shenandoah Valley to take part in a campaign under Major-General Philip Sheridan. Emma’s reputation preceded her, and she made many more clandestine journeys into the Confederate lines, including disguised as a Black washerwoman. In that part, she was cleaning an officer’s coat one day when a packet of official papers fell out of a pocket. Quickly scooping them up, Emma returned to Union lines, where the papers proved to contain useful information.

Emma was again transferred with her unit, this time to Major-General Ambrose Burnside’s forces in Kentucky. Her spying continued, including masquerading as a Southern civilian sympathizer. She fulfilled her mission to assist in discovering a Confederate spy network in Louisville.

Emma and her unit were next sent on what would be her final transfer. Assigned to Major-General Ulysses S. Grant for the Vicksburg Campaign, Emma continued her nursing job in a hospital, but became ill with malaria in April 1863. She was faced with a dilemma—how could she get treatment without having her gender discovered?

Emma was forced to desert. She checked herself into a private malaria hospital in Pittsburgh—as a woman—and quickly recovered. Emma planned to return to the army, but then she saw a list of deserters posted in the window of a newspaper office, which included Private Franklin Thompson. She could not adopt that identity again.

Emma went to Washington, where she finished out the war as a civilian female nurse for the Christian Sanitary Commission.

After the war, Emma wrote a popular, and rather lurid, account of her escapades titled Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, which she later admitted “was not strictly authentic.” The 1865 book sold 175,000 copies and was a best-seller.

Emma became the most famous of the approximately 650 women who enlisted as men during the Civil War, some 250 for the Confederacy and 400 for the Union. Of all these women, only Emma is definitely known to have published a memoir of her experience, becoming the most famous female soldier of the conflict.

Once the book was finished, Emma became homesick. She returned to New Brunswick for a short time before moving back to the U.S. There she married fellow New Brunswicker Linus Seelye in 1867, settling initially in Cleveland and raising three sons, one of whom enlisted in the army “just like Mama did.”

But Emma was not completely happy, as she was still officially branded a deserter in the records. She had served faithfully in the army for two years, not only as a nurse and spy, but also as a colonel’s orderly, postmaster and dispatch carrier, and had seen action at some of the greatest battles of the war. Supported by her friends and fellow soldiers, she petitioned the War Department for a full review of her case.

In 1883, she received an honorable discharge, then in 1884, a special Act of Congress granted Sarah E.E. Seelye, alias Frank Thompson, a veteran’s pension of $12 a month.

Emma lived in several other locations before she settled in La Porte, Texas, where she spent her last few months rewriting her autobiography. She died before it was completed, on Sept. 5, 1898, at 56. In honour of her wartime service, she was reburied in the military section of the Washington Cemetery in Houston in 1901.

Several years after her death, her bravery, daring and resourcefulness were recognized by several institutions. She was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in 1992, the U.S. Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame in 1998, and the Harvey Regional Heritage & Historical Association Wall of Recognition in 2017.

Historical markers were also erected in her honour by the Historical Society of Michigan near the Genesee County Circuit Court building in Flint, Mich., in 1992 and by re-enactors from Company ‘I’, 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment near her Magaguadavic, N.B., home in 2023. The little girl from a New Brunswick farm, who yearned for the freedom that came with being a male in the 19th century, had come a long way.

An illustration from Emma’s 1865 account of her soldiering, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army.[University of Michigan Library Digital Collections]

Advertisement