Conscripts served with units such as Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, shown (above) near Nijmegen, Netherlands, on Feb. 8, 1945. [Lieutenant Dean M. Michael/DND/LAC/PA-153088]

Conscription was the political issue of the Second World War in Canada. And despite promises by the Mackenzie King government before the war to avoid it, the fall of France and public pressure forced the feds to pass the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) in June 1940, which authorized compulsory service for home defence.

But by 1944, after the D-Day invasion of France and the brutal combat in Normandy and the Scheldt estuary, casualties were high and trained infantrymen were in short supply. By November, the military was convinced that only the home defence conscripts could suffice for the needed reinforcements. King finally agreed to send 16,000 of the men who had become known by much of the public derisively as zombies—the soulless living dead of horror movies—overseas.

The pressure on the conscripts to “convert” to general service volunteers had been intense since at least 1942. And money was a factor in the efforts at persuasion. The home defence men weren’t entitled to a War Service Gratuity if they remained in Canada. If they went overseas, however, they would get an additional 25 cents for each day, $7.50 for each 30 days of service, and one week’s pay for each six months of service outside Canada. The additional remuneration was substantial.

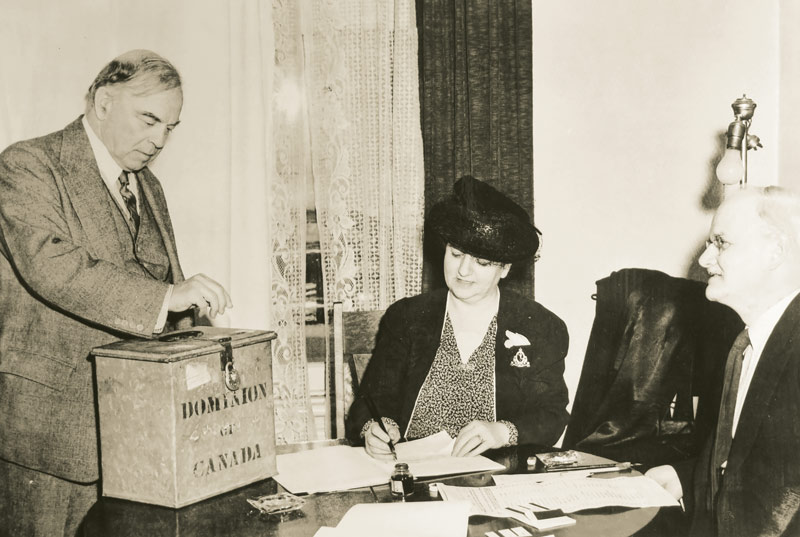

Prime Minister Mackenzie King votes in the plebiscite on conscription on April 27, 1942. [LAC/C-022001]

Interestingly, the NRMA had much to do with enlistment for general service. By way of example, historian Terry Copp studied the 197 men of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve who were killed in action to determine, in part, how they had joined the war effort. Civilian volunteers numbered 130, while another three volunteered for overseas service after they received their conscription notices; 27 volunteered following their home defence service; 22 were zombies sent overseas for service; and there was no information on 15.

Refining the data further, Copp focused on those Maisies killed in action who had enlisted in 1943-1944. There were 23 civilian volunteers; three volunteered on being called up; 16 joined after serving as home defence conscripts; 16 were zombies sent overseas; and there was no information on 14.

In November 1944, home defence conscripts protest the government decision to send them overseas at a training base in Terrace, B.C. [Heritage Park Museum]

Of civilian volunteers then, some, and possibly many, did so when faced with home defence conscription. The same can be said about those who volunteered when they received their call-up notices. Those who converted after home defence service likely did so after being pressed repeatedly to volunteer, to get the benefits offered only to volunteers, or on being ordered overseas by Ottawa or even en route to England. Those who were ordered overseas might well have been hardline anti-conscriptionists throughout their service. What’s certain, however, is that the NRMA played an important role in persuading men to volunteer for military service.

Once the government ordered conscripts overseas, the rate of conversions, which had been stagnant for months, increased rapidly. There were 1,878 in December 1944, 1,692 in January 1945, 2,164 in February and 2,131 in March. The lure of veterans’ benefits was significant.

Men who believed in the cause but had made clear that they were only willing to fight overseas if the government had the courage to order them to do so, also converted after the government’s November 1944 decision.

But, not every zombie accepted the government decision. There were brief mutinies in British Columbia training camps. Some 6,000 soldiers ordered overseas went absent without leave after failing to return from pre-embarkation leave, though substantial numbers returned to their units voluntarily; some men deserted from the trains taking them to their embarkation point, abandoning their rifles and kit; and one zombie tossed his rifle into the water from the gangplank.

In November 1944, home defence conscripts protest the government decision to send them overseas at a training base in Terrace, B.C. [Heritage Park Museum]

All this made news around the world, greatly embarrassing the government, the high command overseas and many soldiers fighting in Italy and Northwest Europe. The latter wrote letters home denouncing the cowardly zombies.

Nonetheless, the NRMA was largely a success. In all, some 154,000 men had been drafted for home defence service, and about 60,000 converted to general service, about 6,000 transferred to other services, and thousands more were discharged for a variety of reasons. By early autumn 1944, there were an estimated 60,000 conscripts still serving, some in formed units, some in training or on courses, some seconded to help bring in the harvest. Trained infantry made up 42,000 of the group.

The widespread opinion in English-speaking Canada was that most of the home defence conscripts were francophones, but this wasn’t correct: 30 per cent spoke only English, 20 per cent spoke only French, 24 per cent were bilingual, and 26 per cent had another first language. They also came from across the country: 25 per cent were from Ontario, 39 per cent from Quebec, 24 per cent from the Prairies, six per cent from B.C, and 6 per cent from the Maritimes.

In other words, the home defence soldiers were generally representative of the Canadian population with only a slightly higher percentage of Quebecers.

Men who didn’t volunteer to fight had many reasons. Some feared being killed or grievously wounded, a rational enough reason in a bloody war. If family members had served during the Great War, many had heard stories of the horror of the trenches and didn’t want to go through their generation’s version of hell. Some were recently married or had young children and didn’t want to be separated from their families. Some were of ethnic origins that didn’t identify with the Anglo-centric views of the military or have any sympathy for the British Empire. Some had religious or cultural reasons for resisting military service. Simply put, not every Canadian wanted to fight.

Conscripts bolstered infantry units such as Le Régiment de la Chaudière, shown here marching along a dike near Nijmegen, Netherlands in February 1945. [Captain Colin C. McDougall/DND/LAC/PA-145767]

But once the decision had been taken to order the zombies overseas, General Harry Crerar, the commander of First Canadian Army, knew that he then had to deal with the possibility that the conscripts might not be welcomed by his men. How could this very dangerous possibility be averted?

Crerar decided that integration was the answer. He sensibly ordered conscripts arriving from Canada be integrated with volunteers in the normal reinforcement stream during their training in England “in order to avoid trouble when [their] draft reached units in the field.” And to avoid distinguishing the NRMA men from volunteers, he insisted on uniformity of dress and had the distinctive serial numbers of conscripts changed to conform with those of volunteers from the same military district in Canada. References to a soldier’s mobilization status were removed from his pay book, too.

At the same time, Canadian Military Headquarters in England worried that conscript non-commissioned officers wouldn’t be acceptable to units in the field and trouble might result if such NCOs tried to give orders to volunteer soldiers. The NCOs were duly reduced in rank.

After their refresher training in England, the now mixed groups of conscripts and volunteer reinforcements began to go to the continent and to infantry units. The battalions weren’t to know which reinforcements were NRMA men, though some figured it out. Lieutenant Donald Pearce of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders wrote on March 20, 1945, that: “There is, of course, a considerable prejudice against” the zombies. “But for some reason they have made excellent soldiers, so far; very scrupulous in the care of their weapons and equipment, certainly, and quite well versed in various military skills.”

The war diarist of The Loyal Edmonton Regiment also appeared to be aware of the presence of conscripted soldiers, writing:

“During the month our [Battalion] has [taken on strength] eight officers and 167 OR’s [and], among the latter, are approx 40 NRMA personnel. These men have in no way been treated differently than any other [reinforcements], in fact the majority of the [Battalion] is not even aware of their presence here, and in the few small actions they have engaged in so far they have generally shown up as well as all new [reinforcements] do.”

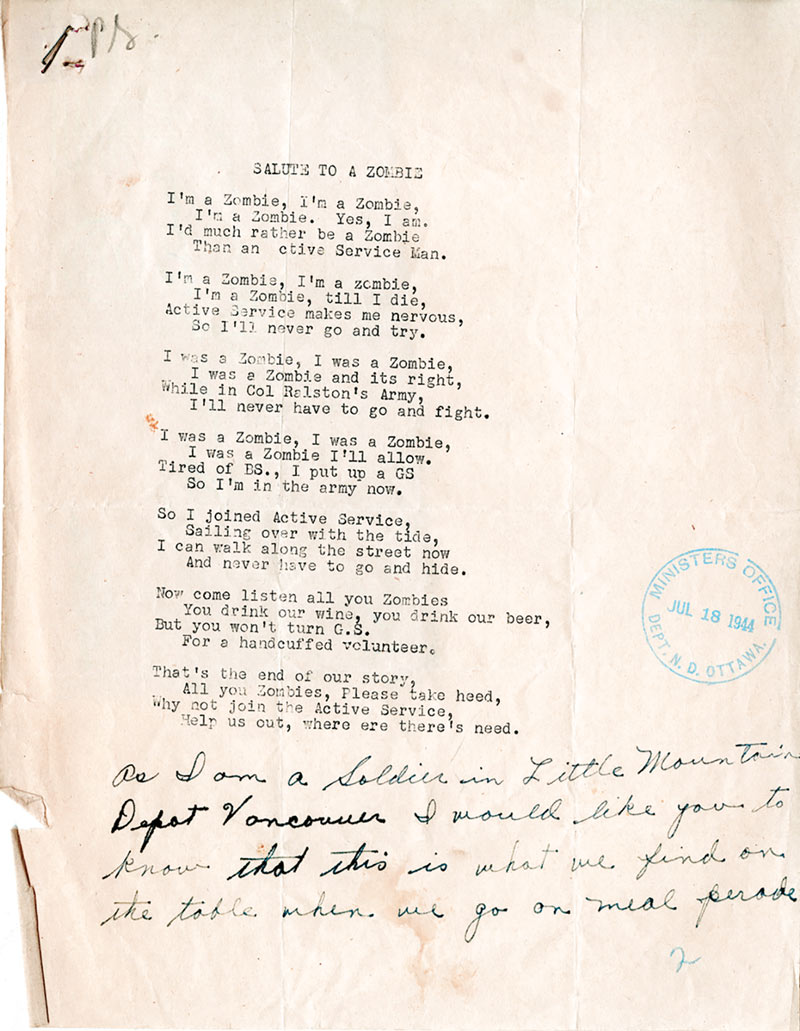

A home defence conscript sent Defence Minister Colonel James L. Ralston the copy of the lyrics to the song “Salute to a Zombie” left for him. [LAC/AC-54-27-63-38]

By this stage of the war, volunteer reinforcements were either young or re-mustered from other trades and given refresher training as infantry. The war diarist of The Algonquin Regiment noted that: “our newcomers are beginning to fit nicely into the family and from the interest they have shown the [battalion] to date they have erased any poor impression they may have given a few days ago and our [officers] and NCOs are now firmly convinced that we have the makings of a fighting team worthy of upholding the name Algonquin.”

The commanding officer of the regiment said as much to reporter Frederick Griffin from the Toronto Star, noting his conscripted soldiers “were just as good any reinforcements we have had.

“Actually,” the CO continued, “nobody knows in the regiment who is a draftee and who is not, and after the boys have been in action, nobody cares.”

A March 15, 1945, story by Ralph Allen in The Globe and Mail had a similar assessment. The conscripts, wrote Allen, “acquitted themselves well on all counts, according to the veterans who fight beside them” in the savage battles on the Rhine-Maas front. “[In] the few cases where home defense soldiers have been introduced to combat at the side of men who knew them to be home defense soldiers, they have been given high marks for courage, training and discipline both by their officers and by their comrades.”

By all accounts, the zombies fought just as well as their volunteer comrades, and the soldiers’ disdain for them during the conscription crisis largely disappeared.

As events developed on the battlefield in the first months of 1945, the shortage of infantrymen that had produced the manpower crisis of late 1944 vanished, too. The men of First Canadian Army fighting in Northwest Europe, hit so hard in Normandy and on the Scheldt estuary, were effectively removed from the gruelling battles for much of November and December 1944, and all of January 1945.

Volunteers, such as these soldiers, continue to arrive in August 1944 as reinforcements, but too few to fill the ranks. [Lieutenant A.A. Schrag/DND/LAC/PA-163407]

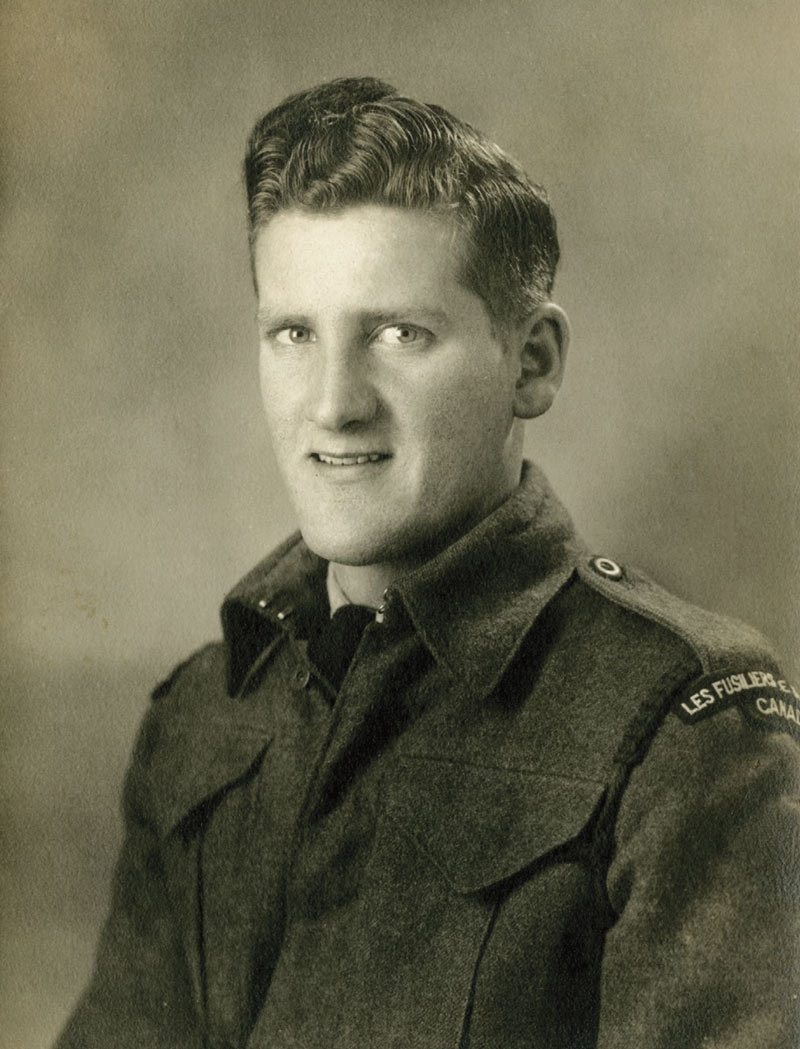

Private René Morin was one of 69 conscripts killed in action overseas. [Mélanie Morin-Pelletier/CWM]

They were almost completely unaffected by the last German offensive in December, the Battle of the Bulge. First Canadian Corps was also moved from Italy to join up with Crerar’s army and was out of action for some six weeks in the first months of 1945. These respites allowed the reinforcement stream to catch up with, and overcome, the losses that had appeared so threatening in the autumn of 1944.

This situation on the ground meant that of the 12,908 conscripts who had proceeded overseas, only 2,463 had been taken on strength by units of First Canadian Army by VE-Day, May 8, 1945. Infantry battalions received 2,282 of these men. Of these troopers, 69 were killed, 232 were wounded and 13 became prisoners of war. Had the fighting continued longer than it did and/or had major battles caused many more casualties, additional conscripts, possibly beyond the 16,000 the prime minister had indicated were required in November 1944, would have been necessary. The late-war manpower crisis, in other words, disappeared even before Germany surrendered.

Private René Morin, an Acadian from Edmundston, N.B., was one of those 69 conscripts killed in action. Drafted in May 1943, Morin joined Le Régiment de Hull in B.C. after his basic training, then in January 1944 transferred to the Sherbrooke Fusiliers in May. After the decision to send conscripts overseas, he proceeded to England in one of the first waves of reinforcements. On April 7, Morin reported to the Royal 22e Régiment, which was fighting in the Netherlands near Apeldoorn. On April 14, a German hand-held anti-tank projectile struck and killed him instantly. Morin was one month shy of his 21st birthday. His time in action lasted just one week.

Advertisement