The First Army, under acting command of Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds (third from right), fought the critical Battle of the Scheldt. He is pictured here with Christopher Vokes (from left), Harry Crerar, Bernard Montgomery, Brian Horrocks (both British Army), Daniel Spry and Bruce Mathews, in February 1945. [Wikimedia]

The ceremonial guests, attempting to ignore the foul weather, stared out toward the Scheldt estuary, where 18 inbound ships made their historic approach to the Belgian port.

They were right to celebrate, even if the looming grey clouds above hadn’t gotten the memo, as the Allied vessels represented a proverbial turning of the tide.

Only a few months earlier, on Sept. 4, the British 11th Armoured Division had entered Antwerp with the intent of seizing, at the time, the second-largest port in Europe.

It was a lofty goal, but an achievable one, especially with the assistance of the Belgian resistance band known as the White Brigade, which wrested control of the dock facilities from German authorities. Alas, instead of pushing further, the British then stopped.

In doing so, 11th Armoured Division left the back door open for the retreating German 15th Army, a force numbering around 90,000, to regroup, reorganize and reestablish itself within the region immediately surrounding the Scheldt River.

Without the wider area secure, Antwerp’s port was effectively rendered useless.

The stage had been set for the Battle of the Scheldt.

Without the wider area secure, Antwerp’s port was effectively rendered useless.

Buffalo amphibious vehicles moving Canadian troops across the Scheldt in Zeeland, 1944. [Wikimedia]

Though not alone in their endeavours, the Dominion troops endured some of the most gruelling engagements of the entire campaign. From the leading role in liberating the Breskens pocket to forging a path onto the enemy-fortified Walcheren Island via its deadly causeway, Canadian forces incurred 6,367 casualties, around half of the total 12,873 Allied losses in the Scheldt.

Finally, with much blood having been split on Belgian and Dutch soil over the preceding weeks, the last German holdouts surrendered on Nov. 10, 1944.

A clean-up operation followed as 267 mines, all scattered throughout the Scheldt estuary, were removed. Only on Nov. 28 was there a clear passage to Antwerp.

So, it was then that British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Allied Naval Commander Bertram Ramsay and other esteemed figures eagerly congregated in anticipation of the official opening of the Scheldt, awaiting the triumphant arrival of 18 ships, marking not just the Scheldt’s opening, but the beginning of a return to normalcy and a tangible snapshot of how an Allied victory in Europe looks.

“The [lead] ship…had been built in a Canadian yard and bore the local and historic name of Fort Cataraqui.”

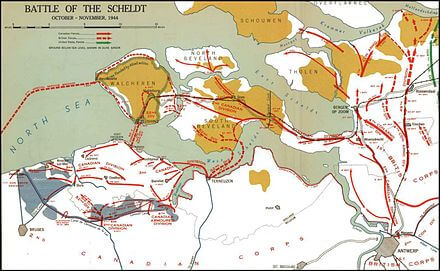

Map of the Battle of the Scheldt. [Wikimedia}

Of all the dignitaries in attendance, not a single Canadian representative had been invited. In a crowd of Britons and Americans, not one member belonged to the army that had played a disproportionate role in making the event possible.

A consolation of sorts was the presence of a Canadian Military Headquarters (CMHQ) historical officer, less an invited guest and more a right-place-at-the-right-time spectator. Major William E.C. Harrison brushed aside the un-Canadian welcome and, in all-Canadian fashion, modestly got on with the job at hand.

“The band struck up with ‘Hearts of Oak,’” the 37-year-old officer recorded. “The ship made fast. The time was 2:30 p.m. The various national anthems were played. All stood in salute. The photographers took their pictures. The correspondents made their notes. The rain poured off the canvas stand in a steady stream.”

And there was even a silver lining in the clouds, so to speak. Finding symbolism in the vessels as they saddled up to the dockside, Harrison noted that the “principal participant in the ceremony was a Canadian. I refer to the [lead] ship. She had been built in a Canadian yard and bore the local and historic name of Fort Cataraqui.”

It was, perhaps, of little solace to the soldiers, sailors and airmen serving under the Red Ensign. Despite the snub, however, not even the Anglo-American delegation would deny that First Canadian Army had made one of the most consequential contributions of the Second World War.

It was just a shame none of them were there to witness it.

—

For more on the Battle of the Scheldt, check out the special edition of Canada’s Ultimate Story: Canada and the Scheldt Campaign.

Advertisement