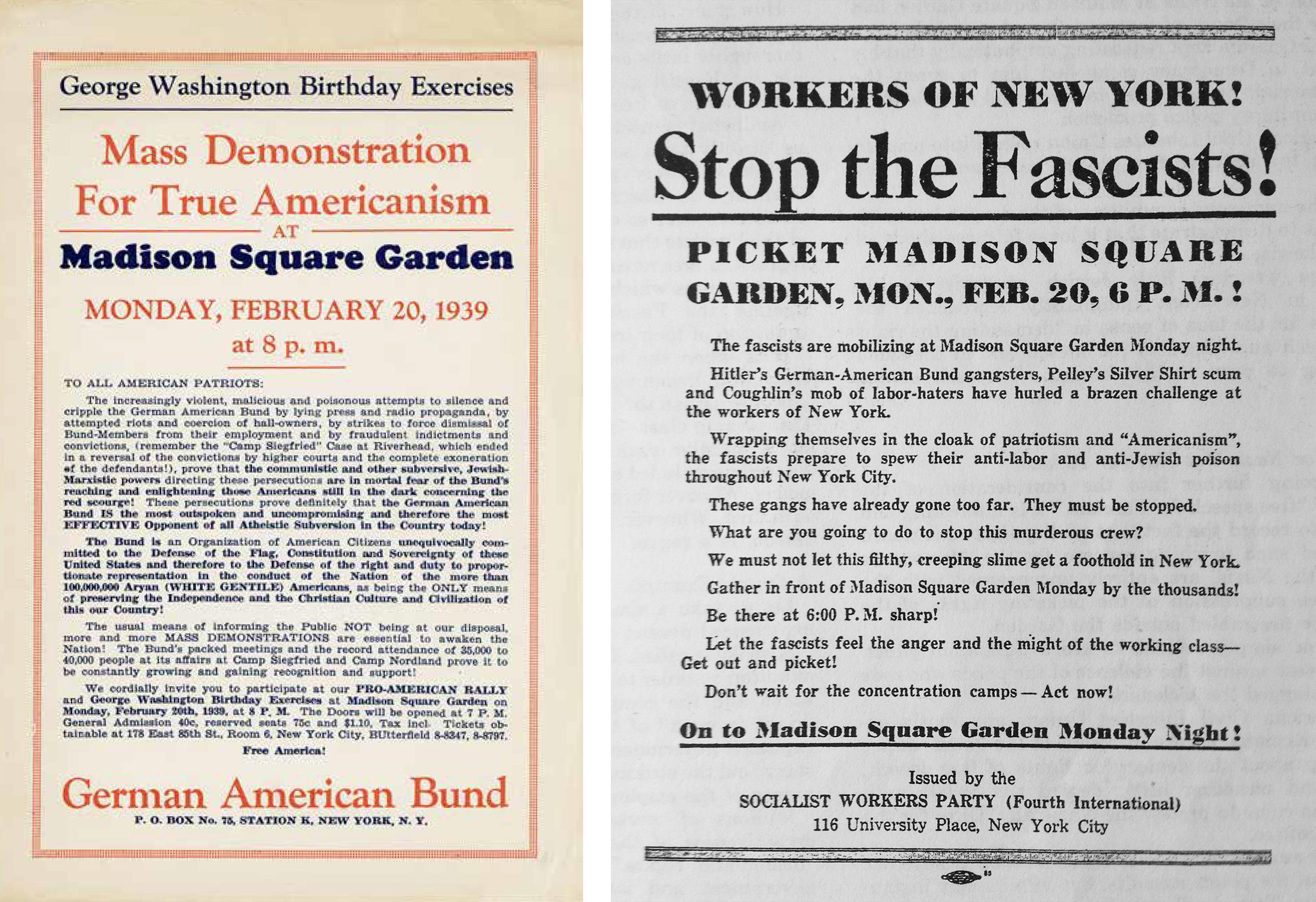

Nazi stormtroopers fill the aisles as the crowd sings “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the opening of the German American Bund rally on Feb. 20, 1939, at Madison Square Garden.

[Larry Froeber/NY Daily News Archive]

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. – George Santayana, Spanish-American philosopher

It’s like something out of George Orwell’s 1984, or Amazon Prime’s TV series “The Man in the High Castle,” which depicts a dystopian America under the rule of war-winning Nazis.

Only, this really happened: a Nazi rally at what was arguably the sports and entertainment capital of the world, New York’s Madison Square Garden, complete with swastikas, brownshirts and jackboots.

It was Feb. 20, 1939. In Germany, Adolf Hitler and his far-right National Socialist German Workers’ Party had been waging an escalating terror campaign against critics, artists, writers, Jews and other non-Aryans for most of the decade.

Empowered by rampant hardship and dissatisfaction about the country’s plight under the Allied-imposed terms of its WW I surrender, Hitler had risen to power on a litany of hate, blame and exploitation outlined in his best-selling manifesto, Mein Kampf.

His intentions had never been clearer. He had restored German pride, albeit misplaced, and military might. He had annexed Austria and was about to overrun Poland. He would single-handedly engineer a second world war that would prove far more devastating than the first, the one they called “the war to end all wars.”

“Nothing is impossible unless one will commands,” he told a September 1935 rally at Nuremberg, “a will which has to be obeyed by others beginning at the top and ending at the very bottom.

“This is an expression of an authoritarian state—not of a weak, babbling democracy—of an authoritarian state where everyone is proud to obey.”

What lay ahead—gas chambers, ovens, a ravaged continent, an atomic bomb—was beyond the comprehension of most at the time. But the writing was on the wall, in the form of an ancient symbol of divinity, spirituality and good luck, appropriated from many cultures and religions and tilted on its corner: the swastika.

Its name, svastika, is Sanskrit meaning “conducive to well-being,” but in Nazi hands it would become one of history’s most-recognized and reviled symbols, forever associated in the western world with conquest, oppression, racism and genocide.

The German American Bund parade on East 86th Street, New York City, on Oct. 30, 1937.

In the land of equality, liberty, freedom and democracy—the United States of America in 1939—the Nazi swastika was integral to the flag of the German American Bund [federation], an avowed Nazi organization.

Founded in 1936, it was led by Fritz Julius Kuhn, a German immigrant, WW I Bavarian infantry veteran, and Nazi sympathizer.

Its membership limited to American citizens of German descent, the organization succeeded the Friends of New Germany, a rabidly antisemitic group that folded after Hitler’s deputy führer, Rudolf Hess, recalled its leaders to Germany and ordered its German members to leave the organization.

The Bund chose its name to silence critics who called it unpatriotic. Its main purpose was to promote a favorable view of Nazi Germany. It did this by circulating pro-Nazi, antisemitic propaganda, blending Nazi imagery with patriotic American ideals. It became the most influential of the pro-Nazi groups operating in the U.S.

Kuhn was initially a capable leader, uniting the organization and expanding its membership, which topped out at around 25,000. But he would ultimately be exposed as an incompetent swindler and a liar, and deported.

Headquartered in New York with training camps in several states, the organization declared America’s first president, George Washington, “the first Fascist” and a “realist” because he had expressed views that democracy wouldn’t work.

On March 1, 1938, with the Bund’s rhetoric and practices causing increasing embarrassment and Berlin anxious to appease American politicians, the Nazi government decreed that no German nationals could belong to the group and no Nazi emblems were to be used by it.

Aware of the risks posed by the impending rally at the iconic Madison Square Garden, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia allowed the event to proceed on the assumption that the highly publicized spectacle would only serve to further discredit the Bund in the public eye.

Still, he dispatched the largest contingent of local police to guard a single event in the city’s history.

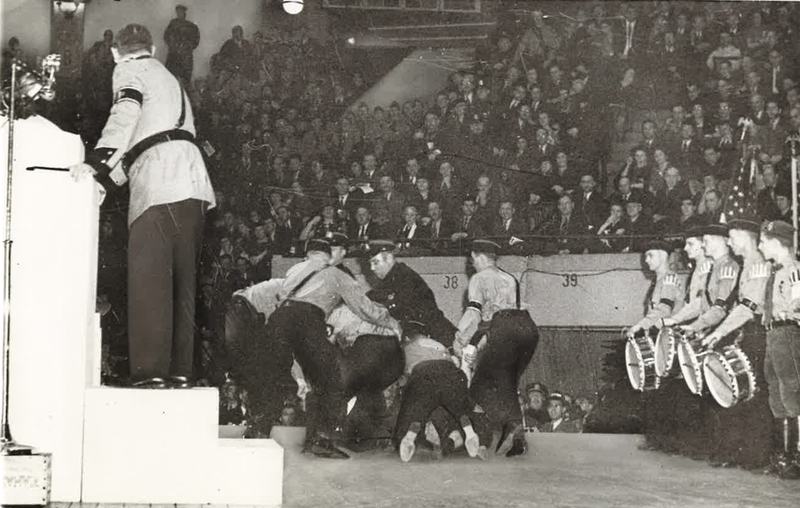

Isadore Greenbaum is subdued and beaten by Nazi stormtroopers at Madison Square Garden.

[The New York Times]

The organization declared America’s first president, George Washington, “the first Fascist” and a “realist.”

The Monday night rally represented the pinnacle of Bund notoriety. Some 20,000 supporters attended; 100,000 opponents demonstrated outside, bearing signs urging America to “Smash Anti-Semitism” and “Drive the Nazis Out of New York.”

At 8 p.m., a loudspeaker in a second-floor window of a rooming house at 49th Street and 8th Avenue began blaring a recorded denunciation of Nazis and urging attendees to “Be American, stay at home.”

Inside, the event was choreographed fascist-style, with uniformed Bundists bearing American and Nazi flags, throwing the Nazi salute, marching to martial music and swaying to German folk songs.

The Bund’s national secretary, James Wheeler-Hill, opened with the statement that “if George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler.”

Midwest leader George Froboese pushed themes of “Jewish world domination,” and blamed the “oriental cunning of the Jew Karl Marx-Mordecais for the class warfare felt across the country.” West Coast leader Hermann Schwinn chose to denounce the Jewish control of Hollywood and news industries.

“Everything inimical to those Nations which have freed themselves of alien domination is ‘news’ to be played up and twisted to fan the flames of hate in the hearts of Americans,” said Schwinn, “whereas the menace of anti-national, God-hating Jewish-Bolshevism is deliberately minimized.”

The last to speak, Kuhn was introduced as the man members loved “for the enemies he has made.”

With a giant picture of George Washington flanked by swastikas draped behind him, Kuhn railed on about Democrats and Jews. He claimed German Americans were being “persecuted in every field of endeavour” while declaring that “no one has a greater veneration than I for the fathers of the republic and the good structure they founded.”

He criticized and belittled U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, repeatedly referring to the country’s eventual four-term president as “Frank D. Rosenfeld.” Roosevelt’s New Deal program to pull America out of the Great Depression was denounced as the “Jew Deal.”

(Siena College’s poll of 157 presidential historians, conducted a year into the term of new presidents since 1982, has consistently placed Roosevelt at or near the top of its best presidents list; its 2022 poll had him at No. 1, just ahead of Abraham Lincoln).

Hundreds of German Americans give the Nazi salute to young men marching in Nazi uniforms at Camp Siegfried on Long Island, N.Y.

Kuhn’s speech was cut short when a man broke through the lines of Bund security, ran onto the stage, and charged the speaker. The interloper was quickly swarmed by the Bund’s paramilitary in what Russel Maloney of The New Yorker described as an “uncanny replication of Nazi thuggery [as] a pack of uniformed men blast[ed] away with fists and boots on a lone Jewish victim.”

Twenty-six-year-old plumbing assistant Isadore Greenbaum was pulled away by police, saving him from serious injury. Kuhn concluded his address with a call to establish an America ruled by white gentiles, free from a Jewish Hollywood and news.

“The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of white gentile stock, and an American citizen imbued with patriotic zeal. Therefore: Join!”

The crowd chanted “Free America! Free America! Free America!” as their leader exited the stage. Proceedings concluded about 11:15 p.m. It was the biggest Nazi rally in U.S. history.

As departing attendees buttoned up overcoats covering their unforms, a punch-up erupted outside between protesters and Bund stormtroopers. Four people were arrested.

The Bund subsequently came under federal investigation. Its financial records were seized in a raid on its New York City headquarters, authorities discovered that US$14,000 (about $307,000 in 2023) raised by the Bund during the rally were unaccounted for.

Investigators found that Kuhn had spent the money on personal expenses, including a mistress. The organization didn’t seek to have Kuhn prosecuted, operating on the principle (Führerprinzip) that the leader had absolute power.

Nevertheless, New York City’s district attorney prosecuted him in an attempt to cripple the pro-Nazi group. On Dec. 5, 1939, Kuhn was sentenced to two-and-half to five years in prison for tax evasion and embezzlement.

Kuhn’s successor as Bund leader was Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze, a spy for German military intelligence who fled to Mexico in November 1941, shortly before the Dec. 7 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Mexican authorities forced Kunze to return to the U.S., where he was sentenced to 15 years for espionage. He was replaced by George Froboese, who was at the head of the organization when Germany declared war on the United States, four days after what Roosevelt had dubbed “a date which will live in infamy.”

Froboese killed himself a year later, after receiving a federal grand jury subpoena. The German American Bund faded from existence.

Years later, Isadore Greenbaum, a former chief petty officer in the U.S. Navy, described how he snuck into the rally with the intent to simply listen.

“I went down to the Garden without any intention of interrupting,” he told an interviewer, “but being that they talked so much against my religion and there was so much persecution I lost my head and I felt it was my duty to talk.

“Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing Hitler’s behind—while thousands cheered? Well, I did it.”

Greenbaum was charged with causing a disturbance and sentenced to 10 days in jail. He paid a $25 fine and was released.

Advertisement