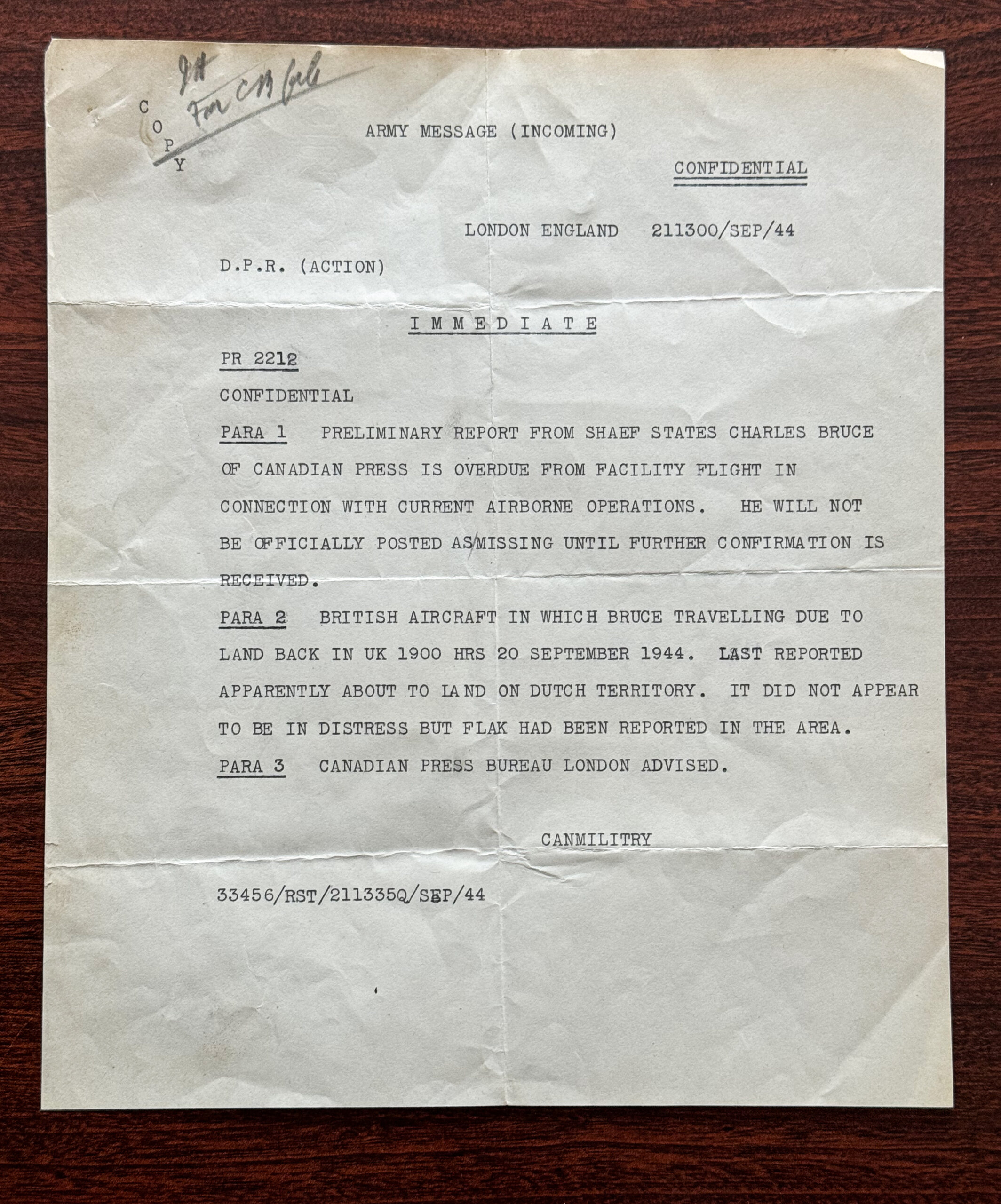

The Sept. 21, 1944, message from SHAEF informing The Canadian Press that Charlie Bruce’s plane was overdue.

[CP]

It bore troubling news from General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force: a plane carrying the superintendent of the wire service’s overseas operations, Charlie Bruce, was 18 hours overdue.

Bruce had been covering a resupply mission over the German-occupied Netherlands during the Allies’ ill-fated attempt to bring the war to an early end—an airborne invasion called Operation Market Garden, later to be memorialized in the star-studded 1977 Hollywood film A Bridge Too Far.

The mission was straightforward. The British bomber, possibly a Stirling, on which Bruce had hitched a ride was to drop canisters of equipment and supplies over Dutch territory, then head home with the rest of its formation.

It was due back in England at 7 p.m. on Sept. 20, but was, the message said, “last reported apparently about to land on Dutch territory. It did not appear to be in distress but flak had been reported in the area.”

The news had to have sent chills through all CP staff. One of Bruce’s predecessors as senior CP correspondent in London, Sam Robertson, was among nine Canadians killed on April 29, 1941, when U-552, skippered by U-boat ace Erich Topp, torpedoed the steamship Nerissa off the Irish coast as the CP writer returned from leave in Canada.

A total of 207 were lost; three stowaways were among the 91 survivors.

(Nerissa’s 57-year-old master, Captain Gilbert Radcliffe Watson, had just survived his fourth sinking in two world wars when he assumed command of the ship in August 1940; he did not survive his fifth.)

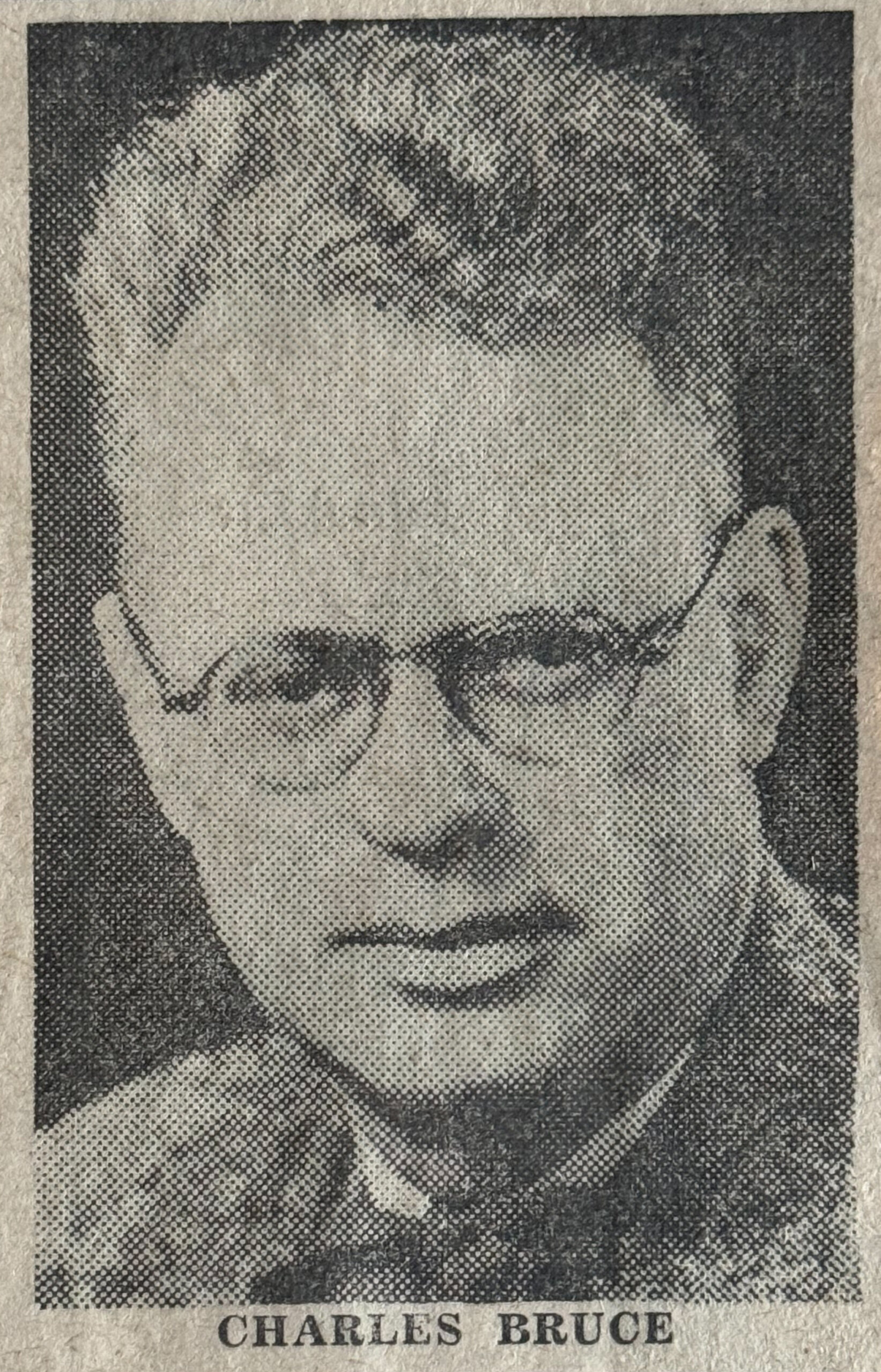

Charlie Bruce was a Canadian Press war correspondent who worked alongside the likes of Ross Munro and Bill Stewart out of the wire service’s London bureau. Both his son Harry and grandson Alec became journalists.

[CP Archive]

CP’s London bureau oversaw a formidable stable of journalists through WW II, including Bill Stewart, Bill Boss and the dean of Canadian war correspondents, the legendary Ross Munro, who covered both the Dieppe Raid and, along with Stewart, the D-Day landings.

Canadian Press war correspondents Ross Munro (left) and William (Bill) Stewart (centre), study a map with the Montreal Gazette’s Lionel Shapiro in La Villeneuve, France, on Aug. 13, 1944.

[Ken Bell/CP/LAC]

Like so many CP staff before and after him, he made the rounds, returning to Halifax as night editor, then moving to Toronto as assistant news editor and, later, news editor and general news editor.

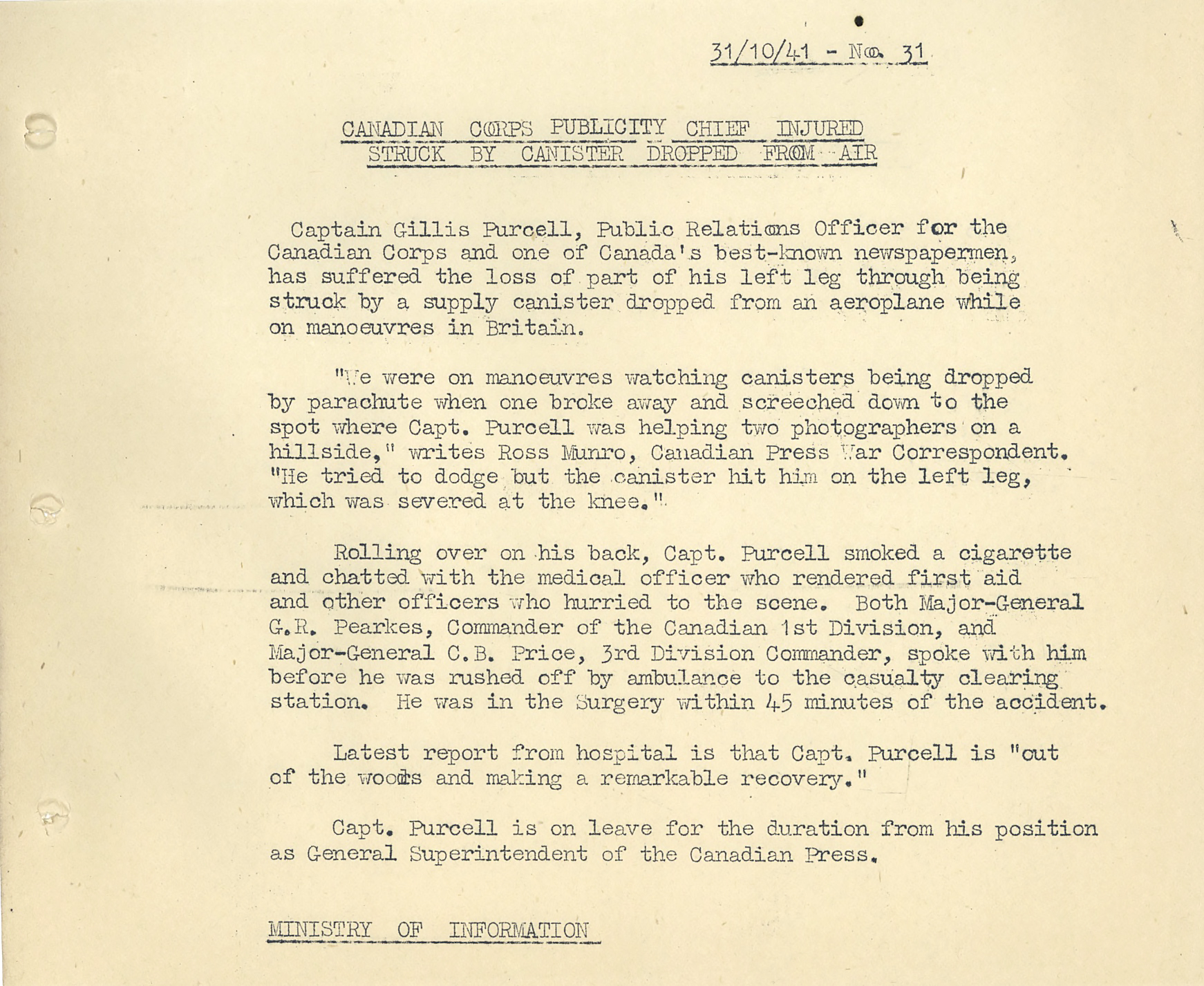

He spent the first year of the war back in the wire service’s New York bureau handling overseas news, then returned to Toronto to serve as acting super while the storied Gillis Purcell, who famously lost his left leg above the knee during manoeuvres in 1941 (CP writers have been required ever since to identify a leg amputation as above or below the knee), was overseas with the army.

A government statement announces the accident that took Gil Purcell’s leg above the knee.

[University of Texas Repository]

His acclaimed poem “Personal Note” explored the idea that goodwill and mutual helpfulness is the proven secret to the survival of all peoples, and that it was these things that the Nazis threatened:

And so we strike at Hitler and the tribes

Infused with the contagion of his ill.

We strike to halt a rot at the root of living.

We strike instinctively,

Strike to survive;

Not as a man, not as a nation, not as a race,

But as mankind.

Married with three children, Bruce arrived in London early in 1944, charged with the responsibility of guiding CP’s European staff in their work during the war’s final stages and directing the transition to what in some respects would be the even more daunting task of covering its aftermath.

His philosophy and way of working were wire service hallmarks and remained the standard at CP for decades.

“He kept impressing on CP men [there were few women in the industry at the time] the absolute necessity of knowing their subject thoroughly,” said a CP report, “and he insisted that the news be adequately interpreted for the layman reader.”

He wrote that a man writing a story about British agriculture, for instance, “should know more about it than he can get from books in the Ministry of Agriculture.”

“He ought to know what an English farm looks like and how it feels to handle a manure-fork.”

Author of the first CP Stylebook—for many organizations, it remains the bible of news and corporate writing—Bruce characterized his new job as his toughest and most absorbing assignment yet: “In war reporting, the action is everything.”

Said a CP account of his disappearance: “It was in search of an essentially ‘action’ story that he made the flight from which he did not come back.”

Bruce didn’t know he had been missing.

The Canadian Press maintained a bureau in London throughout the war, dispatching reporters to cover fighting on most major fronts, including Italy and Normandy.

[Regina Leader-Post]

Then, out of nowhere, he walked into the CP London bureau as if nothing had happened. Doug Amaron, another wartime wire service stalwart, wrote that the previously missing man “discovered the staff searching files for biographical material to answer London newspapers’ requests for his obituary.”

Amaron described Bruce’s “look of astonishment” as colleagues Ross Munro and Alan Nickleson “jumped from their desks, clapped him on the back and shook hands with him.”

Bruce didn’t know he had been missing and apologized for “all the flap.” Then he promptly began writing the story of his two-day adventure. Like the good CP reporter that he was, he got the names and hometowns of every crewman.

His gripping account, raw with deletions and additions pencilled in, begins with pilot Doug Robertson of Vancouver taking the aircraft in low over the drop zone “through a literal hell of flak.”

“From the puffs and flashes lower down, it appeared that sharp fighting was in progress on the ground,” he wrote. “The big plane went down to dropping level and the haze of dark smoke below us, already punctured with flak flashes, was stippled with the multi-colored parachutes of the supply canisters.”

Aircrew in full flying kit walking beneath the nose of Short Stirling Mark I.

[Wikimedia]

“Then the flak slammed into us,” Bruce wrote. “It smacked ‘P for Peter’ with the shock of a giant fist. For a split second the aircraft seemed steady in her course. Then she went into a screaming nosedive.

“Robbie was standing back on his heels trying to pull her out of it as I shot out of the second pilot’s seat, where I had been spotted to get a better view of operations.”

Somehow, Bruce and Roseblade switched positions, with the reporter ending up in the bomb-aimer’s compartment “staring down at Dutch field[s] and houses through an open parachute escape hatch.”

“I didn’t know whether I was expected to jump or not.”

Paratroopers assemble near Mk IV Stirlings of 620 Squadron during Operation Market Garden in September 1944.

[Wikimedia]

“Robbie had tugged her back to an even keel and he and Rosey were cursing, cajoling and muscling the ship along on some kind of [a] temporary course.”

Robertson and Roseblade were now flying with their knees jammed against the controls to keep the aircraft straight and level. Flak had smashed the port tailplane and punched holes all along the fuselage.

“No one will ever know what it did to the plane’s bottom because that is pressed so hard into the earth of that field outside Ghent.”

Prowse was scrambling to determine their location and a way out of enemy territory. The engineer, Flight-Sergeant Ronnie Anderson of Manchester, was attempting what Bruce described as “an aerial version of ‘mend and make do’” on the damaged plane.

In the tail gunner’s turret, British Sergeant George Hopkin spoke calmly on the intercom while the wireless operator, Fight-Sergeant George Thompson of London, England, was “at his table with blood running down his back and hunks of flak in his shoulders and hip.”

The plane’s trim controls had been shot away. An hour or so later, Robertson would bring the crippled aircraft down on newly liberated Belgian soil in gathering dusk.

“It was a lovely belly-landing,” Bruce wrote. “Lying in the crash position as we scraped along I felt no more discomfort than if I was standing on a harrow being dragged along rocky ground.

“We scrambled through the hatch, dropped to the ground, ran a few yards in case the aircraft caught fire, and then got down and kissed the earth.

“There was a good deal of rough reverence in that gesture.”

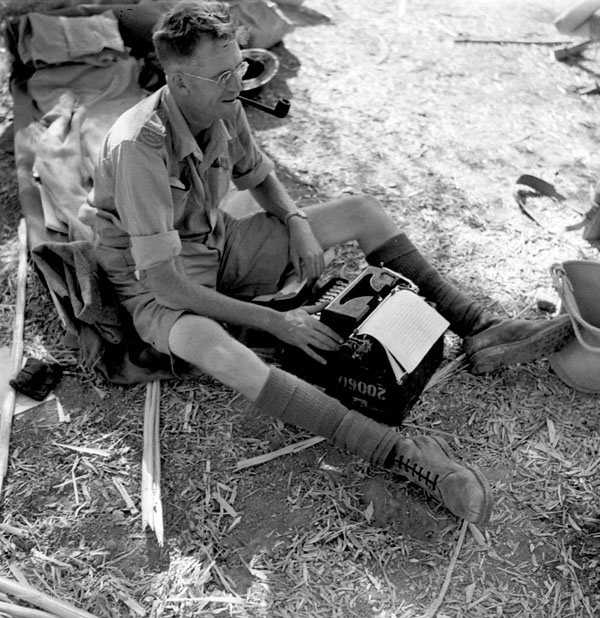

Canadian Press war correspondent Ross Munro works on a story in the battle area between Valguarnera and Leonforte, Italy, in August 1943.

[CP/Wikimedia]

Five minutes before Bruce arrived in the office, Munro was searching his desk drawer for a photograph. “I wish Charlie would walk in now and tell me to get away from his desk,” he said.

Then Bruce did walk in, followed by a reporter from a press trade journal seeking the picture for an obituary. She unexpectedly got a first-person account of his ordeal instead.

Edmund Townshend, a reporter for the London Daily Telegraph who was aboard another aircraft on the same operation as Bruce, baled out after at least one of his plane’s four engines was taken out by flak. He was rescued by a Dutch farm family, hidden, fed and eventually delivered to British tankers by partisan fighters.

Advertisement