A mud-caked Private Donald Johnston Mackinnon, 25, of the 73rd Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada) returns from fighting on the Somme front, probably in September 1916.

[George Metcalf Archival Collection/CWM/19920085-028]

More than 30 nations declared war between 1914 and 1918. Their uniforms were a sartorial feast for the eyes—splashes of red, blue, white and gold. There were capes and greatcoats; kilts and kepis; busbies, bearskins and patent leather boots.

“This stupid blind attachment to the most visible of colours will have cruel consequences,” declared French politician and general Adolphe Messimy, who commanded a brigade at the Somme, and later a division.

Colonial units, especially, came to the continent dressed to impress—cascading robes, baggy pantaloons known as seroual or shalwār, brilliantly coloured accoutrements, and variants of the inordinately tall red fez present-day North Americans tend to associate with parading Shriners. They were traditionally worn by wealthy Arab traders as a sign of status, its red dyes vivid and expensive.

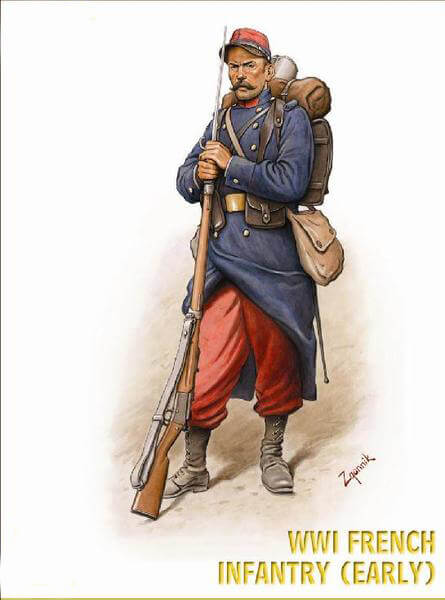

A French pantalon rouge in his early-WW I uniform. The colour scheme didn’t last. [Hat Toy Soldiers]

Belgian reservists defended their homeland in 1914 wearing top hats. While the British entered the war decked in drab khaki adapted from lessons learned in colonial India, the French sported long blue coats and rich red pants, for which the troops had been known as the pantalon rouge since the 1870s.

Belgian carabiniers wear top hats during the Battle of the Frontiers in August or September 1914.

[IWM/Q70232.Wkimedia]

The Germans wore a more appropriate dull grey uniform, topped by the spiked German pickelhaube helmet made of leather and designed to deflect sabre blows to the head, not shrapnel or bullets. The Austro-Hungarians retained their peaked cloth caps and had summer and winter versions of their uniforms with differing material weight and collar styles.

The British were still wearing soft caps, animal fur and ostrich feathers when the war broke out, while some European armies clung to the ornate tall hats that they had worn in the days of musket balls and cavalry sabres.

A colonial tirailleur from French Equatorial Africa, possibly Senegal, is ready to fight in 1914. Tirailleurs were light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns.

[Bain News Service/U.S. Library of Congress]

“Looking at the uniforms, one can see that they were designed more to look smart than to protect or camouflage. Bear in mind that, apart from the fighting in the colonies, Balkans and the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, most European powers had not experienced a large-scale conventional war since the Franco-German war of 1870.”

The German pickelhaube helmet was made of leather and designed to deflect sabre blows to the head, not shrapnel or bullets. It was replaced the year after the war began.

[Stijn Butaye Collection/Pondfarm/Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The woolen material of the British fatigues wasn’t ideal, and it had one major flaw.

Commanders stubbornly, often disastrously, clung to 19th century strategy and tactics, ordering mass attacks across open terrain in the face of gas, artillery, machine guns and, later, tanks. Yet armies adapted quickly to more practical wear.

The 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) wore regimental tartan kilts and the highly visible red-checkered Glengarry cap during the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915. After paying a high price in helping stop the German race to the sea in west Belgium, it was khaki Balmoral bonnets—a floppy beret with a pompom on top—and plain khaki apron over the kilt for the rest of the war.

The French abandoned the red pants and long coat for a dull blue-grey (they called it horizon blue) uniform in 1915 on the assumption that a man in blue silhouetted against the sky would be harder to spot. The dye was also cheap and already in stock. After the war, the battered French army would turn to “American khaki.”

Algerian soldiers arrive at a French railroad station during the early days of the First World War. Algerian troops bore the brunt of the first poisonous gas attack on April 22, 1915.

[Uncredited]

In 1915, the Germans simplified their 1910 feldgrau kit, removing details on the cuffs and other elements, making them easier to mass produce. They dispensed with the expensive practice of maintaining an array of regional uniforms for special occasions, a remnant of earlier times when German states each had their own uniform, creating a confusing array of colours, styles and badges.

“British khaki was perhaps ahead of its time,” said Augustyn. “It was not as conspicuous as the French uniforms, although the Germans were also not that visible in their grey feldgrau uniforms.”

-

A French postcard from 1915 depicts colonial troops preparing to fight during the Battle of the Marne.

[Butler Library/Buffalo State College]Good socks were at a premium, and often made by volunteer women back home. A typical pair might only last a few days during long-distant marches.

The woolen material of the British fatigues wasn’t ideal, and it had one major flaw that cursed wearers for the rest of the war: it absorbed water like a sponge—a particular disadvantage during what turned out to be a war-long deluge of rain and cold in northern France and the west Belgium town of Ypres.

The town, now known by the Flemish Ieper (EE-per), had ironically been a renowned textile trading centre since medieval times. It was here where the two sides fought largely stagnant battles for most of the war, reducing Ypres to rubble.

The British Brodie helmet was introduced in 1915. This one doesn’t appear to have saved its wearer.

[ Steve Douglas Collection/Stephen J. Thone/Legion Magazine]The present-day U.S. army helmet provided no better blast protection than its First World War predecessors.

Multiple reports from the period estimate that more than half of early-war deaths were the result of shrapnel or artillery shell fragments, often to the head. Steel helmets were a natural alternative.

France abandoned the woolen kepi and equipped its soldiers with steel helmets in 1915. They were named for their creator, General August-Louis Adrian. Inventor John L. Brodie followed later that year with the British Brodie helmet, designed to protect against shrapnel while maintaining mass-production-friendly simplicity.

The Belgians adopted the French design, adding their country’s rampant lion insignia. New uniforms were modeled on the British khaki.

The Germans tested the Allied helmets extensively, then distributed their own Stahlhelm (steel helmet) in early 1916. Its style, which saw Germany through two world wars, informed the design of the Advanced Combat Helmets used by many Western forces today.

A 2020 study published in the online journal PLOS One found that the present-day U.S. army helmet provided no better blast protection than its First World War predecessors and, indeed, the vintage French Adrian helmet actually outperformed the modern American design.

The four biomedical engineers from Duke University in Durham, N.C., mounted the original British, French and German helmets of the First World War, along with the present-day American helmet, on sensor-equipped dummy heads and aligned them with a cylindrical shock tube to simulate an overhead blast.

The team then generated primary blast waves of different magnitudes based on estimations from historical shell blasts. Peak reflected overpressure at the open end of the blast tube was compared to measurements at several head locations.

They also did bare-headed tests.

“All helmets provided significant pressure attenuation compared to the no-helmet case,” said their paper. “The modern variant did not provide more pressure attenuation than the historical helmets, and some historical helmets performed better at certain measurement locations.

“The study demonstrates that both historical and current helmets have some primary blast protective capabilities, and that simple design features may improve these capabilities for future helmet systems.”

The Duke researchers could find no record of helmet shockwave testing in the scientific literature. Their study focused on an overhead blast scenario more common to trench warfare, which was considered dated before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in which the nature of the fighting has been compared to 1914-1918.

A 2020 study deemed the French Adrian helmet the most effective against concussive blasts of any helmet ever made. But it didn’t appear to help this French trooper.

[Steve Douglas Collection/Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]The pattern ’08 webbing could not, however, be produced in the quantity required.

Many historians consider the British Expeditionary Force that went to war in 1914 the best-equipped army in Europe.

The full set of 1908 webbing could weigh more than 32 kilograms. But the equipment was well designed, and the weight evenly distributed, according to historian William Fowler, author of the 2011 book Battle Story: Ypres.

The pattern ’08 webbing could not, however, be produced in the quantity required. The volunteers of Kitchener’s Army had to make do with leather equipment for load-carrying.

In 1915, recalled Victor Packer of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, a battalion coming out of the line at Ypres could march up to 20 kilometres to a rest camp.

“You still had in those days, a full pack, 250 rounds of ammunition, water bottle, haversack, rifle, bayonet, and often you carried a bit of something extra as well,” he told historian Max Arthur for the book Forgotten Voices of the Great War.

“We were daft enough to carry souvenirs in those days like nose caps of shells and things or an Uhlan’s helmet, whatever we could get like that we prized, but not long afterwards we threw them over a hedge or somewhere.”

Advertisement