Stijn Butaye with his magnum opus, a scratch-built, working replica of a British Mk IV tank. [Stephen J. Thorne]

A short time later, the boy recovered a mud-encrusted, near-century-old Lee-Enfield rifle. His mother’s reservations notwithstanding, Butaye was hooked.

Twenty-plus years later, and the farmer’s son—an electrician by trade—has collected about 500 wartime objects from the farm property and surrounding area: bayonets, rifles, pistols, grenades, detonators, helmets, mortars, artillery shells, buttons, badges, uniforms and a cache of stone jugs that bore the daily rum ration for the Tommies in the trenches.

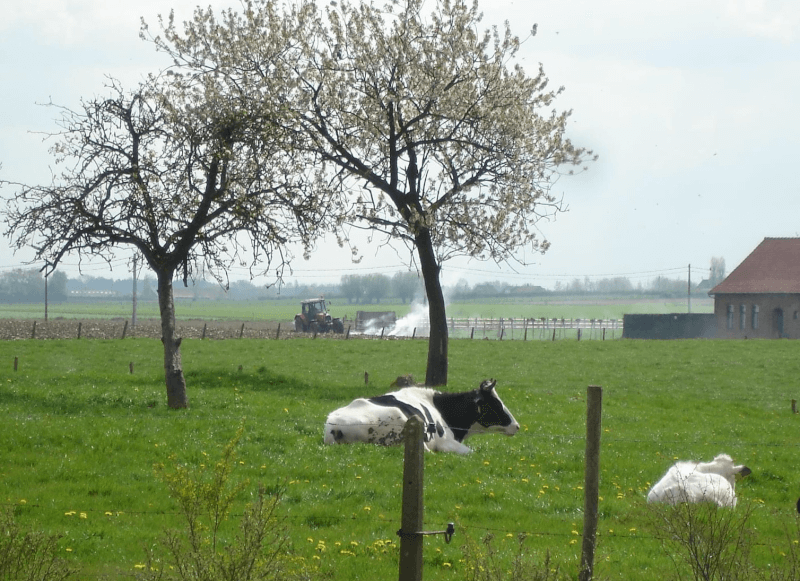

It’s called the iron harvest and each spring and fall, especially, Belgian farmers planting and harvesting across Flanders and elsewhere along the Western Front routinely unearth unexploded ordnance, discarded weapons, even human remains that rise through the mud in the fields where Allied and German troops staged largely stagnant, muddy though bloody, warfare between 1914 and 1918.

Located northeast of Ypres (the French spelling, pronounced EEE-pruh, but known today by the Flemish Ieper, EEE-per), the property—actually two farms at the time—was situated in the middle of the front between Passchendaele, Ypres, Langemark-Poelkapelle and Saint Julien.

Welcome to Pondfarm. [Stephen J. Thorne]

It has belonged to the Butaye family since 1960, when Stijn’s grandfather Frans—who had resented the Germans ever since WW II Wehrmacht troops requisitioned a previous home in 1940—bought the land, re-christened it Pondfarm, and promptly blew up all 38 German bunkers.

All, that is, except one which proved too close to the brick barn and adjacent house and damaged their walls with even a tempered blast. “The barn was cracking; the basement was cracking; my grandmother was complaining it was very loud,” said Butaye. “She was very angry.”

So, the partially damaged bunker stubbornly remained and now forms part of Stijn Butaye’s private museum that also includes trench art and a painstakingly crafted, working replica of a British Mk IV tank.

Stijn Butaye with a Belgian Mauser rifle and bayonet he discovered on the farm. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Tens of millions of artillery shells flew back and forth, leveling Ypres and its famous Cloth Hall.

The land has been farmed since the 1700s—everything from dairy cattle to potatoes, cabbage and sugar beets; corn, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower and wheat. It became a battlefield early in the First World War, when the German advance to Belgium’s North Sea coast and the French ports around Calais was stopped at Ypres—‘Ipern’ to the Germans, dubbed “Wipers” by the Allied troops.

A salient formed around the town, a trade centre since medieval times. Tens of millions of artillery shells flew back and forth, leveling Ypres and its famous Cloth Hall, along with virtually everything for miles around. Villages and settlements became ghost towns.

Even the farms suffered as munitions pummeled the naturally muddy topsoil that ran from less than a metre to three metres deep. Almost a third didn’t explode due to factory flaws (mass production took precedence over quality), wet fuses and soft ground. They have lain in the oxygen-deprived soil ever since.

A British Webley revolver (foreground) with a German Luger and Mauser C96 semi-automatic pistol behind, part of Stijn Butaye’s First World War collection at Pondfarm. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The clay that lies beneath the topsoil is non-porous—perfect for making the bricks that built nearly every homestead in the region; excellent for preserving millions of wartime artifacts; not so helpful when it comes to drainage. That has traditionally been provided by roadside ditches, but the incessant shelling of WW I destroyed the ditches. The mud became so deep that soldiers drowned in it like quicksand.

Canadian General Arthur Currie had his headquarters at Pondfarm briefly in 1915, narrowly escaping a direct hit from a German artillery shell by jumping out a window during the Second Battle of Ypres—one of five battles in the area.

It was during this spring action when the Germans employed chlorine gas for the first time, releasing it from steel cylinders with rubber hoses and letting it drift with the wind toward the Allied lines.

As the main gas cloud hit French colonial troops from Algeria on the Canadians’ left flank, not far from Pondfarm, the chlorine burned their throats and caused their lungs to fill with foam and mucus, effectively drowning them in their own fluids.

A belt of machine-gun bullets remains intact after more than a century. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“One cannot blame them that they broke and fled. In the gathering dark of that awful night they fought with the terror, running blindly in the gas-cloud, and dropping with breasts heaving in agony and the slow poison of suffocation mantling their dark faces. Hundreds of them fell and died; others lay helpless, froth upon their agonized lips and their racked bodies powerfully sick, with tearing nausea at short intervals. They too would die later—a slow and lingering death of agony unspeakable. The whole air was tainted with the acrid smell of chlorine that caught at the back of men’s throats and filled their mouths with its metallic taste.”

The Canadians could only watch before they, too, were targeted as they tried to fill the six-kilometre gap created by the first attack.

The gas “came up and went over the trenches and it stayed, not as high as a person, all the way across,” said Lester Stevens of the 8th Battalion (90th Winnipeg Rifles). “Two fellows, one on my right and one on my left, dropped. And eventually they got them to hospital, but they both died.

“I was a bit of an athlete in those days and a good swimmer, and I could hold my breath. As soon as I saw that gas coming, I tied a handkerchief over my nose and mouth. That saved my life.”

An astute army might have capitalized on the opportunity—that was the intent, after all—but the Germans stopped short and dug in, apparently lacking reinforcements (they were stretched thin, with troops also fighting on the Eastern Front) and fearful of their own little-understood weapon.

A 4.5-inch British gas shell sits by the side of a road near the spot where Canadians first took up positions on the front line outside Ypres. [Stephen J. Thorne]

More than 6,500 Canadians were killed, wounded or captured in the Second Battle of Ypres. Today, the Saint Julien Memorial, commonly known as the Brooding Soldier, memorializes the battle and marks the site of the first gas attack.

A breakthrough had been prevented, but the salient shrunk and Pondfarm and nearby Saint Julien had been lost. Generalfeldmarschall Gottlieb Graf von Häseler, in his late-70s at the time, immediately ordered construction of 38 reinforced concrete bunkers on the site, the largest of them 60 metres long.

Others were up to 45 metres long and included sleeping quarters, a dressing station and gun positions. The farm became a fortress, complete with tunnels, cellars and a narrow-gauge railway system.

Kazerne Häseler—Pondfarm—would remain in German hands through parts of three more major battles in two-plus years, costing more than 1.5 million casualties on all sides. The property changed hands several times during the Battle of Passchendaele (the Third Battle of Ypres), in which Canadians ultimately took the hilltop town east of the farm in 1917.

Pondfarm was finally secured by Belgian forces on Sept. 28, 1918.

Today, the Canadians’ route into Passchendaele is called Canadalaan. A Canada Gate stands at the head of the street adjacent to the memorial at the site of Crest Farm, an elevated German strongpoint that was the centre of the most stubborn resistance encountered by the Canadians entering the town.

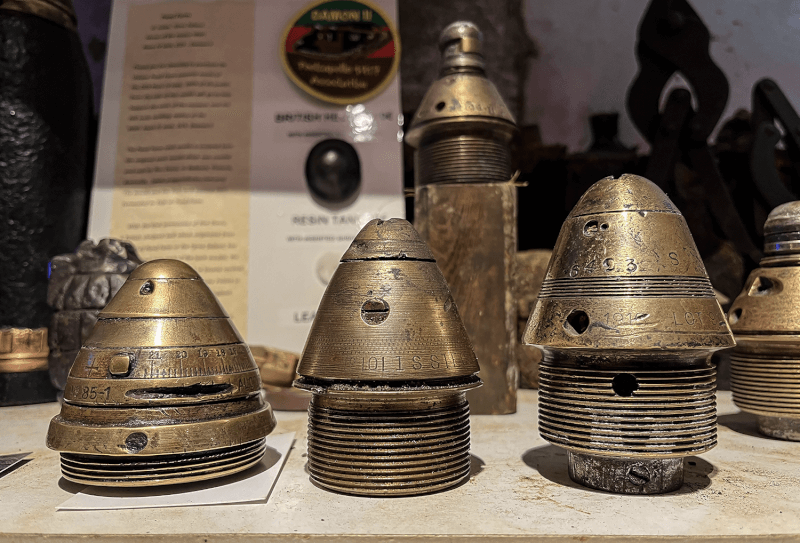

Century-old fuses sit on the shelf in Butaye’s private barn museum. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Shells of all types, including chemical, still regularly emerge from the depths.

“The stronger the winter, the more metal rises up, and the better harvest for me,” said Butaye. “The metal is wet; the water turns to ice and swells up, and that’s how the soil cleans itself.”

Farmers leave the munitions by the roadsides, like used milk bottles, and call the police, who inform DOVO-SEDEE, the Belgian military’s bomb disposal (EOD) unit, which comes to pick them up. Its motto is “percula non timeo” (I fear no danger).

In 2022, the brigade’s three companies were called out 3,506 times, and recovered 20,111 munitions in Belgium, the vast majority of them in Flanders, including 536 in and around Ypres alone. Among them: 1,434 French 75mm shells, 2,348 German 7.7cm shells, and 5,091 British 18-pounders. The unit video that imparts this information is delivered to the accompaniment of death metal music.

I showed DOVO Adjudant (master sergeant) Steven de Meulenaere, a former paratrooper, pictures of munitions I had stumbled upon in just two days of exploring Flanders with historians Steve Douglas, a Canadian based in Ypres, and Erwin Ureel, a Belgian military veteran. Among those he identified: a 4.5-inch British chemical shell; a British 18-pounder; shell fragments and fuses with booster caps; a Belgian mortar and rifle grenades.

DOVO stores the shells, analyzes some, and destroys them all in batches several times a year. The methods of destruction vary with the types of shells—sealed, pressurized chambers for chemical weapons; craters in a field at the EOD facility in Langemark for high explosives.

Most of the munitions are still live, a fact that is brought home periodically when the tiller blades, or harrows, that farmers drag behind their tractors to churn the soil at planting time detonate one.

In 2010, Butaye’s mother snapped a picture as his father accidently drove his tractor over a gas shell, a pale, menacing cloud wafting away in the salvational breeze. He was uninjured.

Stijn’s father encounters a gas shell in the fields of Pondfarm. [Courtesy Stijn Butaye/Pondfarm]

“When they accidently hit the fuse on the top of a shell, it can detonate. They’re always lucky. The [tractors] are made of very strong steel and it absorbs a lot of the explosion.”

Farmers can claim damages from the Belgian government, provided they do it within six months and have DOVO certification that the blast was caused by military ordnance.

The costs of disposing of gas shells manufactured before 1925 is the responsibility of the country in which they were deployed. Demolition of post-1925 chemical weapons, such as those used by the Japanese in the Second World War, is the responsibility of the country that deployed them.

“It’s interesting work,” said de Meulenaere. “I’m doing what I have been trained for. And being in the military in a civilian environment, it’s also nice to have contact with the people. It’s just a nice job; it’s reality. And you’re also working on your national security; you’re participating by making your country safer.”

Part of Stijn Butaye’s collection of original British Supply Reserve Depot stone jugs, which were used to distribute the daily rum ration to the Tommies in the trenches. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The gas attacks around Saint Julien and on the farm itself killed virtually every living thing in their path, even the hated rats. Postwar, the farm property was shifted 100 metres back from its original location.

“After the war, it took the previous farmer a lot of time to clean the fields. When he arrived here, they had to mark their borders with oil [which they lit] and covered their ears from the explosions.”

The new owner filled in the plethora of shell craters covering the property with horse and plough going in circles, a painstaking, time-consuming exercise. Farmers in the area couldn’t plant again until the late-1920s or early-1930s, said Butaye.

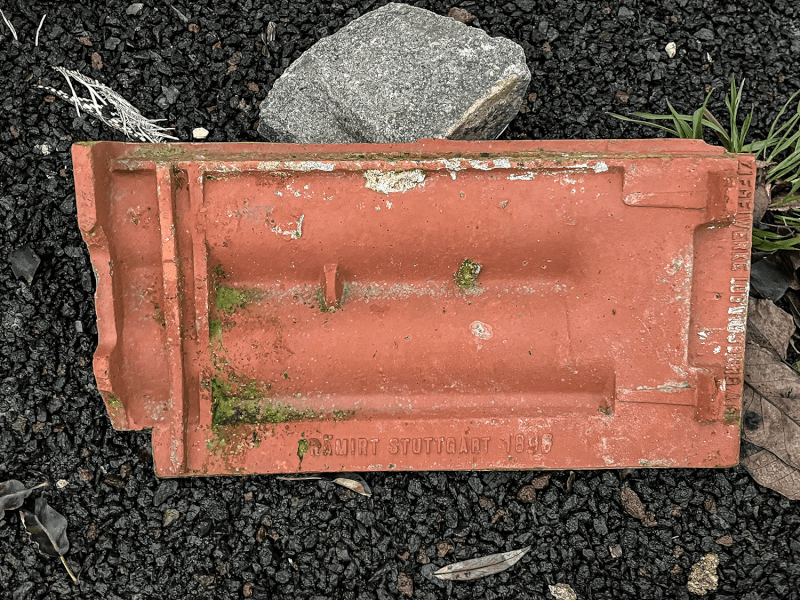

One of the roof tiles from Stuttgart that constituted First World War reparations to Pondfarm, stamped 1898. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Over the years, visitors would come by the farm and tell stories of how a grandfather or great-uncle had died there during the war.

“And that’s how I got interested,” said Butaye. “Then I said ‘I have to do something here; I can’t ignore it. It’s everywhere in the fields.’ And then an old schoolteacher said ‘Stijn, you need to do a project about the First World War.’”

More specifically, he did his project on “Pondfarm and the First World War.” He went on to make his own website.

“If you are driving with the tractor, you see all that stuff. Sometimes, we even found a boot still with the bones inside. Then you find another part of a human soldier and…ya, it’s everywhere. Even the dog finds it. How crazy it is.”

He’s found bayonets, German and Belgian Mauser rifles, machine guns and unspent ammunition belts, along with the duckboards the troops walked on in the trenches—now virtually unfindable after more than a century in the mud.

But it’s the personal items Butaye finds most interesting “because they mean something.”

“A soldier holds it; a soldier uses it. It’s very strong. I have families who come visit and say ‘oh, my grandfather could have used that.’”

Identifying the former owners of items captivated Butaye. Few of the leather dog tags of the day survived decades in the mud, but soldiers would carve their names into spoons or other items. Butaye tries to track down relatives, but it’s difficult.

Butaye’s working Mk IV tank replica sits inside Pondfarm’s brick barn. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Eventually, he and his teacher decided to reconstruct a tank. They acquired blueprints for a British Mk IV, assembled a team of experts, solicited the aid of machinists and began a years-long project to create as close to a replica as possible. The stunning result can be converted from male (with cannons on the sides) to female (with machine guns) and back again.

Butaye operated his pride and joy at a tank rodeo in Britain last summer.

His private Pondfarm collection is approved by the Belgian government, local police and DOVO. A licensed detectorist, all Butaye’s finds are reported to authorities.

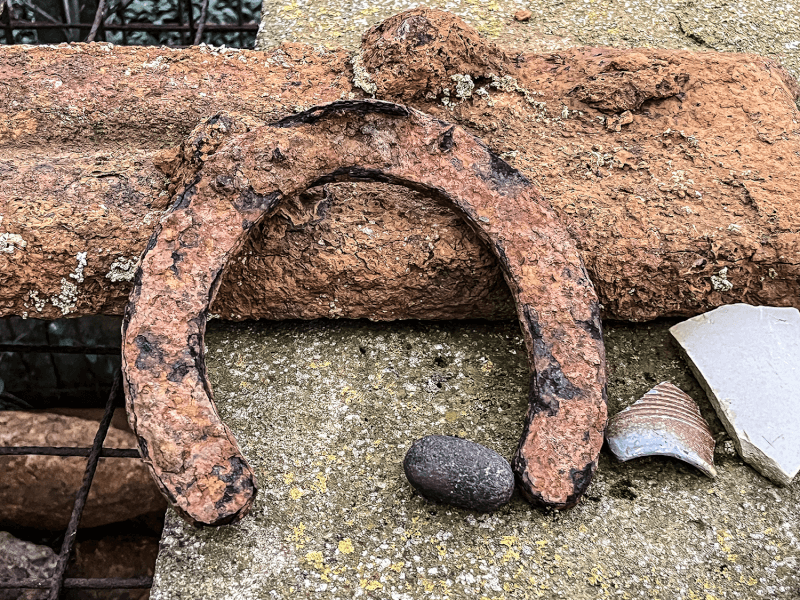

A warhorse threw a shoe on Pondfarm. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“My dream is to open the farm to more visitors, and I want to have visitors from both sides,” he said. “And that means the Germans are welcome, as well, because everyone did what they had to do. The Germans were at the beginning afraid to come over here. Now you see a couple of them already. But they are scared to go to [the nightly memorial ceremony at] the Menin Gate, but I want to change that.”

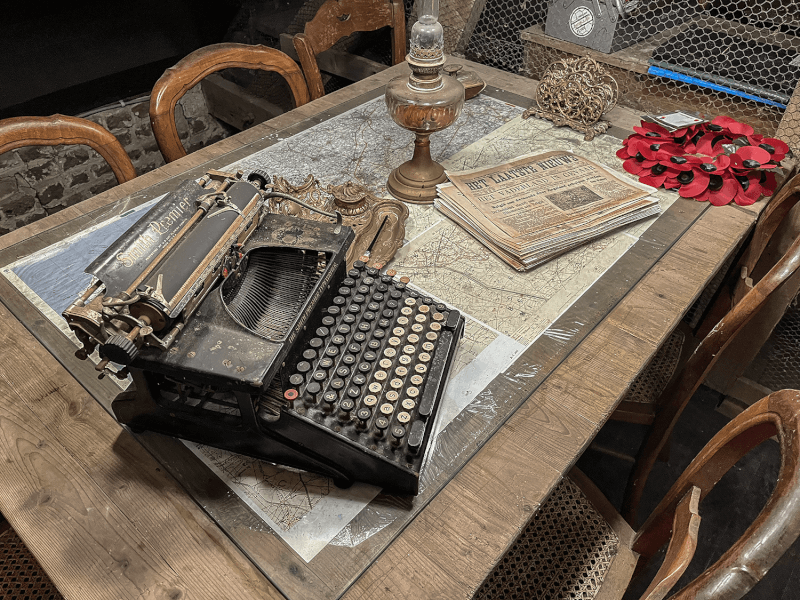

A period typewriter and table along with newspapers in the loft of Butaye’s barn museum. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Declares Butaye’s mission statement: “It is the wish and ambition of the Butaye family that visitors meet and fraternize with mutual love and respect. Someone who visits the Pondfarm takes with them a memory that makes an impression from history, but we also provide perspective and inspiration for the future.”

—

This is the first in a series of columns on Flanders. Next week: The story of German chemist Fritz Haber and the development of chemical warfare.

Advertisement