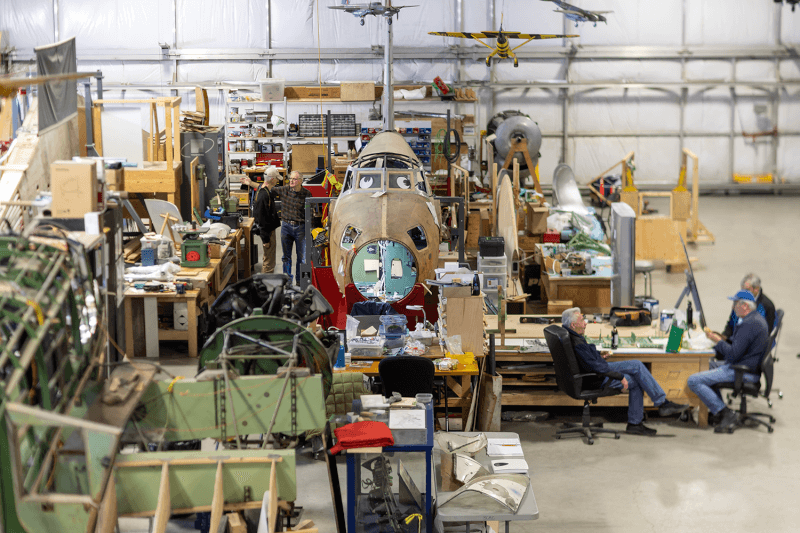

The 1940s-era Mosquito restoration project has just passed its halfway point in the Bomber Command Museum of Canada hangar at Nanton, Alta. Volunteers hope to finish the job in another decade. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Theirs is a meticulous labour of love, conducted by volunteers whose collective experience amounts to hundreds of years of pouring through voluminous manuals, amassing specialized tools and scrounging elusive parts.

They are master craftsmen and problem solvers, innovators and artisans, all working toward a common goal—resurrecting one of the most intriguing warbirds of the Second World War, an all-wood, twin-engine de Havilland Mosquito.

Largely stripped of parts by the time the Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society got their hands on it, the plane’s caretakers have searched the far corners of the Earth to find the scarce materials and vanishing expertise to rebuild the unique aircraft.

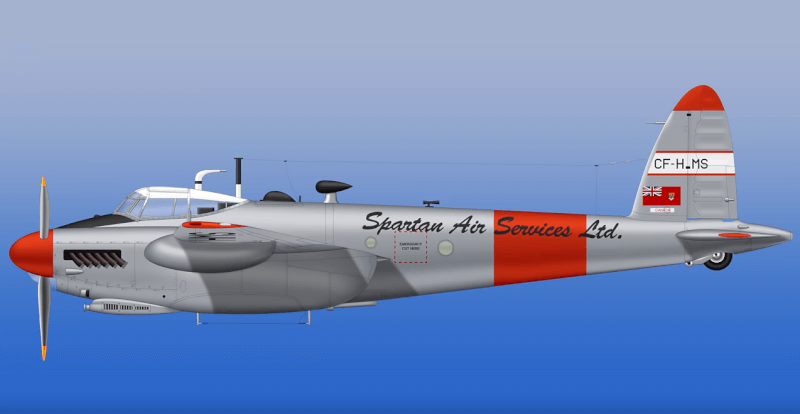

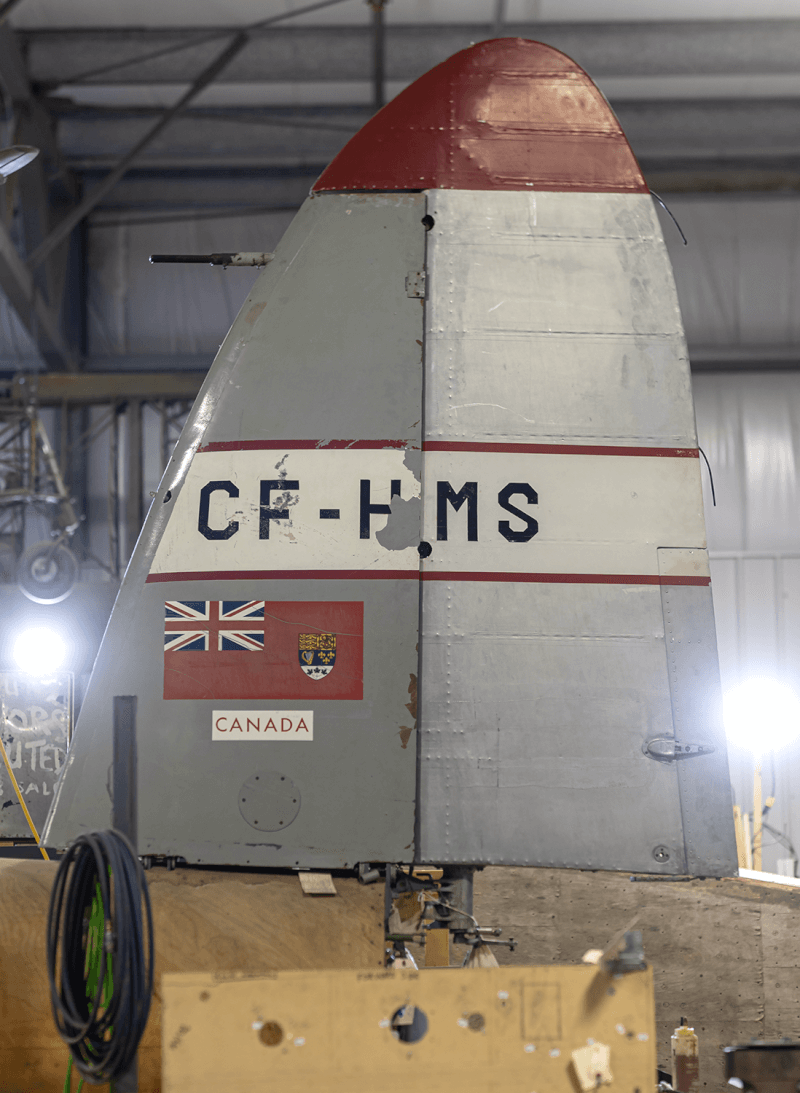

They’ve been at it 11 years and it will take 10 more to get Tail No. RS700 (CF-HMS) to the non-airworthy taxi status where its owner, the City of Calgary, wants it.

Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society volunteer Andy Woerle works away under the watchful eyes of aircraft No. RS700, now in mid-restoration. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“Aircraft maintenance guys form the bulk of our restoration group and this is their retirement project,” said Richard de Boer, founding president of the Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society. “They’re thrilled to be able to work on this airplane.

“It’s kind of a crowning achievement for some. It’s a feather in their cap. The opportunity to work on a Mosquito and to apply their lifelong-acquired skills is rare—and valued.”

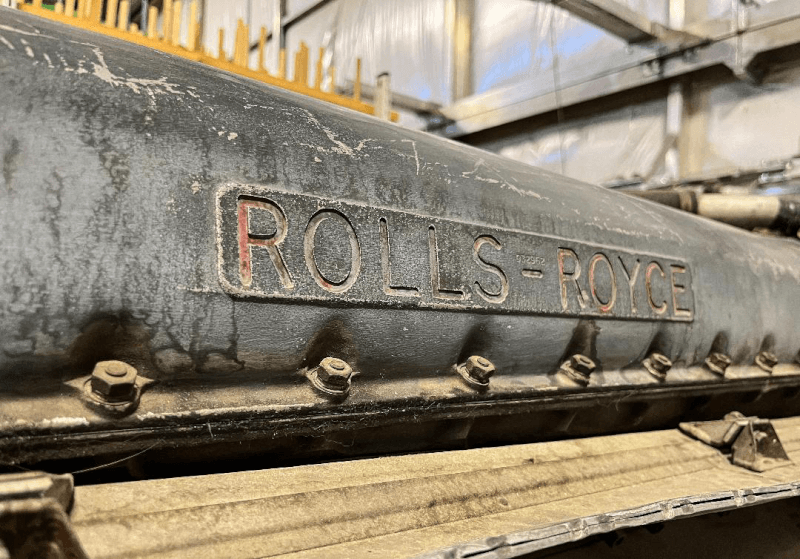

The plane’s Rolls-Royce Merlin engines will roar to life again one day. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“So, we never turn anybody away,” he said. “If you have no skills, we’ll teach you.”

The oldest volunteer was in his 90s. One of the youngest started as a 13-year-old, convincing his father to chauffeur him 90 minutes out to Nanton from Calgary every Saturday—until this year, when he entered the engineering program at Western University in London, Ont.

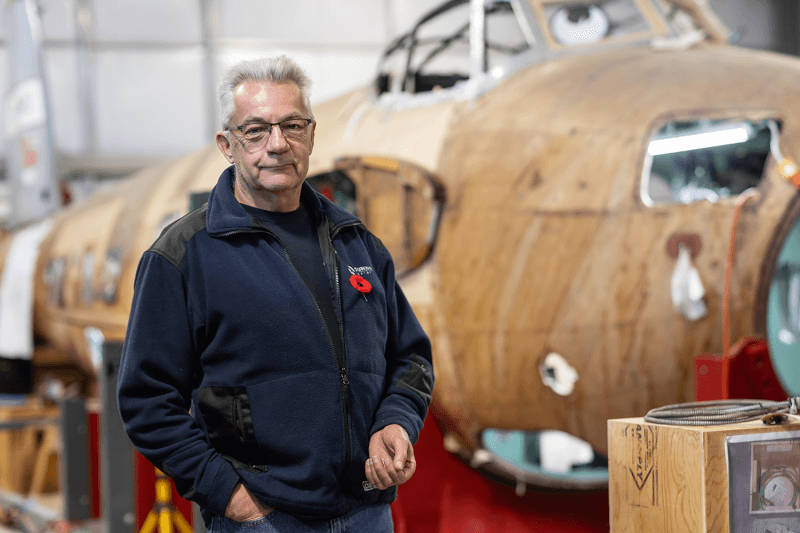

Richard de Boer, founding president of the Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society, with his partially restored charge. The 11-year-old project is expected to take another decade to finish. [Stephen J. Thorne]

It sat in the elements for several years before 403 (Reserve) Squadron took it.

RS700 is one of only 31 Mosquitos still in existence. Just four are airworthy; only two are actually flying, one of which is based at KF Aerospace in Kelowna, B.C.

Technically speaking, the Calgary plane was never exactly a warbird.

Both it and its sister aircraft in Kelowna were once owned by Spartan Air Services, which won a federal government contract in the mid-1950s to capture the first 3D aerial mapping of the entire country. Company aircraft conducted multiple sweeps over some two million square miles (more than five million square kilometres) of territory using bulky Wild Heerbrugg RC-8 large-format cameras from Switzerland.

Some two million of the project’s 230mm-square negatives are stored in Ottawa.

Produced by Airspeed Ltd. at Hampshire, England, in 1946, RS700 was among the last Mosquitos built under wartime contracts. It spent four years in storage before it was converted to a prototype of what would become the PR.35 high-altitude, pressurized photo-reconnaissance aircraft.

What would become known as the “Calgary Mosquito” served three years in the Royal Air Force, survived two fires and was awaiting disposal when Spartan picked it up along with 14 others, five of which it scavenged for parts.

Dressed in the company’s silver with red trim, RS700 photographed large swaths of the country from 1956-1960, one of just four Spartan Mosquitos to survive the ordeal. It also conducted aerial surveys in Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

One of the Swiss-built Wild Heerbrugg RC-8 large-format cameras that 3D-mapped Canada in the 1950s sits on a table next to the Mosquito in Nanton, Alta. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Arriving in Calgary aboard a CN train, the aircraft ended up in an oil field pipe storage yard belonging to Shell Canada, where it sat in the elements for several years before 403 (Reserve) Squadron took it in 1968.

It wasn’t until the early-1970s that the plane finally found a home inside a hangar, where volunteers removed what was left of its tattered fabric. Two years later, assets of the failed air museum were sold to the city, including the Mosquito and five other aircraft. Stewardship was transferred to the Calgary Aerospace Museum.

In 1989, the plane was taken out of storage and shipped by road to Cold Lake, Alta., where members of 410 Squadron, RCAF, planned to restore it to the type’s original military configuration. The plan faltered a year later when the project leader was transferred to Georgia, and the Mosquito was returned to Calgary virtually untouched.

RS700 languished for two more decades until the city council awarded its restoration to de Boer’s newly formed society. The work was subsequently moved to the Bomber Command Museum, which has marginally more space than the city’s aerospace museum. They’re restoring it to Spartan’s configuration.

Profile of the Calgary Mosquito in its Spartan livery.[Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society]

It was their secret stealth missions that gave the Mosquito a panache that few aircraft have achieved in more than a century of flight.

The Mossie, as the wartime Mosquito was affectionately known, forged its reputation at low-level in the skies over Nazi Germany and occupied Europe.

While larger, more heavily armed bombers such as the Lancaster and B-17 lumbered along with their massive payloads, the all-wood, lightly armed Mossie could fly lower, higher, faster and further, albeit with a fraction of the hitting power.

The birch plywood, spruce and Ecuadorean balsa from which the Mosquitos were made were readily available. Component fabrication was contracted out to furniture factories, cabinetmakers, luxury-auto coach builders and piano makers. No rivets needed, their surface was smooth and battle damage easily repaired.

The Mossie was adapted to multiple roles, including daytime tactical bomber, high-altitude night bomber, a pathfinder for the heavies, day or night fighter, fighter-bomber, intruder, maritime strike aircraft and fast photo-reconnaissance aircraft.

But it was their secret stealth missions that gave the Mosquito a panache that few aircraft have achieved in more than a century of flight.

They thrived on pinpoint, low-altitude, hit-and-run raids that did more to boost Allied morale and discourage the enemy than impose significant damage on Nazi infrastructure. No dam busting or Dresden firestorms for these guys.

In 1942, Mosquitos targeted the Gestapo headquarters in Oslo. They launched similar attacks on the dreaded Nazi police force in Aarhus, Jutland, Copenhagen and elsewhere. Mosquitos also destroyed various SS facilities.

And they did it with pizzazz.

In Jutland, the raiders went in so low that a crewman saw a Danish farmer in a field salute as they zoomed past. In Copenhagen, they flew down boulevards and banked into side streets.

Once their exploits became known, the British press—and public—ate them up with glee.

On Feb. 18, 1944, several Mosquitos from 21 Squadron, RAF, participated in Operation Jericho, a low-level attack on the German prison in Amiens, France. The raiders busted down walls, destroyed guard towers and freed 258 prisoners, a third of them French Resistance fighters (182 were recaptured). (See footage of the raid.)

de Boer holds up a pair of the 230mm-square negatives used by Spartan to map the country in the 1950s. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“The Germans could run, but they couldn’t hide,” Wilkinson explained. “Nobody was safe from the Wooden Wonder.”

Collateral losses could be high, however. More than 100 prisoners died in the Amiens attack, and the Nazis performed 260 reprisal executions in the aftermath.

At a Catholic school in Copenhagen, 27 nuns and 87 children were killed by wayward bombs during a March 21, 1945, raid depicted in the 2021 Danish film “The Shadow in My Eye” (Skyggen i mit øje), on Netflix as “The Bombardment.”

But, as Stephan Wilkinson wrote for Aviation History Magazine in 2015, the effect of such well-timed and -targeted attacks on the German psyche was “extreme.”

“The Germans could run, but they couldn’t hide,” Wilkinson explained. “Nobody was safe from the Wooden Wonder.”

Not even the Luftwaffe chief, Hermann Göring himself.

On Jan. 30, 1943, three Mosquitos famously mounted a daylight raid on the main Berlin broadcasting station, precisely timed to arrive just as Göring—who had overseen creation of the hated Gestapo—began an 11 a.m. radio address commemorating the Nazis’ 10th anniversary.

The broadcast was rescheduled, but not before sounds of the attack aired live over German radio. At 4 p.m. that afternoon, more Mosquitos interrupted a radio address by the Nazi propaganda minister, Josef Goebbels.

They were largely nuisance raids, and they infuriated Göring, whose frustration with his own Luftwaffe mounted as its dominance over European skies slipped.

“It makes me furious when I see the Mosquito,” he once said. “I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminum better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again.

“What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses, and we have the nincompoops. After the war is over, I’m going to buy a British radio set—then at least I’ll own something that has always worked!”

Mosquito RS700 (CF-HMS) will be restored in the livery of Spartan Air Services, the company that 3D photo-mapped the entire country in the 1950s. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The restoration team is committed to historical accuracy.

Back in Nanton, the volunteers are working what, in the end, will look like magic.

But, really, there’s no magic to it. It’s just difficult, painstaking work—stripping rotten, weather-worn plywood sheets from the salvageable wooden strips, called stringers, that form the skeletons of the wings. The project’s difficulty is exacerbated by the fact the plane’s 1940s-era urea-formaldehyde glue remains bound and determined not to surrender a single square centimetre of the plywood shell without a fight.

“Stripping” the plywood off the wings would be too easy for this crew. Because the glue is so tough, they actually have to router 474 square feet (44 square metres) of plywood off, turning it all to sawdust as they go.

A view of one of the Mosquito wings with its wooden stringers, brass screws and some of the original plywood still attached. [Stephen J. Thorne]

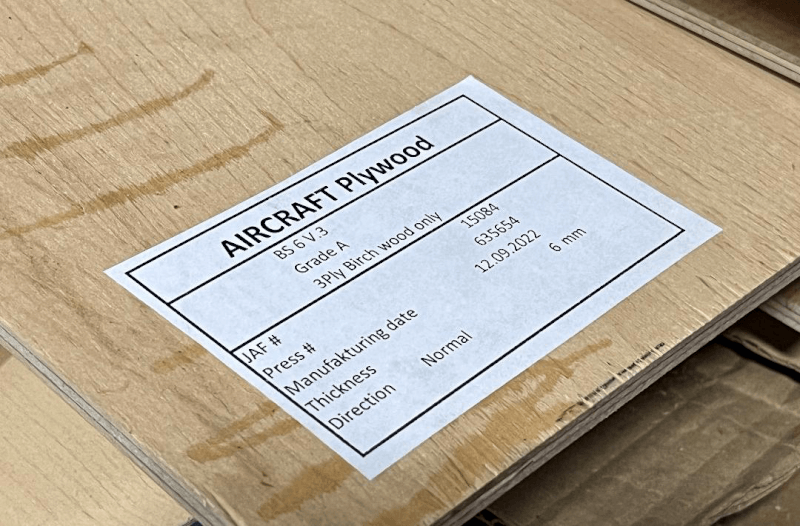

Just the tops of the wings require 13 sheets of Baltic birch plywood, three-ply in five different specifications—1.5mm-6mm thick, each composed of three veneers, or layers, ranging from 0.5mm-2mm apiece.

A fresh sheet of the plane’s hard-to-get plywood awaits installation. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“But if you go back from there, it runs lengthwise along the waterline of the airplane. And then there are sheets on the wing where the grain goes crossways on the sheet. So every sheet of plywood that we’ve purchased for this airplane is custom-made and custom-ordered for its thickness and grain direction.”

Volunteer Dick Snyder searches for an elusive piece of the 1940s-era Mosquito at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada hangar in Nanton, Alta. [Stephen J. Thorne]

In addition to that stubborn adhesive, the wood is attached to the skeleton by 40,000 hard-to-replace inch-and-a-quarter, No. 5 slotted-head brass screws, 25,000 of them on top of the wings alone. Each is spaced to precise specs.

“Today, there is only one mill in the world that will make British Standard 6 V.3 plywood and, ironically, that mill is in Austria,” birthplace of the Führer himself.

de Boer, whose varied aviation career has included curating museums in Calgary and Hamilton, proudly points to a spanking new sheet of plywood stamped BS 6 V.3 and declares that it’s “made to the exact same specifications as what de Havilland used on their airplanes in 1940.”

“We are particularly proud of the fact that we are going as authentic as we possibly can,” he says.

Yet the already-complex process is compounded by several more factors. The plywood, air-freighted from Austria, was $850 a 10×15-foot (3×4.5-metre) sheet when the team bought its first batch for the fuselage and tail surfaces a decade ago. The price has since nearly tripled.

“It gets a little expensive,” said de Boer. “And we could have cheated. We could have gone to the local aircraft supply store and bought aircraft-grade, but it’s not British Standard 6 V.3.”

And when they tried to order plywood for the wings last year, the Austrian mill told them they couldn’t supply it anymore because the source material comes from northern Russia, and Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has brought Western-allied trade with Russia to a halt.

So de Boer went on a year-long, worldwide quest to find another mill that could do the job, appealing to firms elsewhere in Austria and into Canada, Finland, Estonia and the United States before he tracked down one in New Zealand that builds brand-new Mosquito airframes and had an expert able to mill him what he needed.

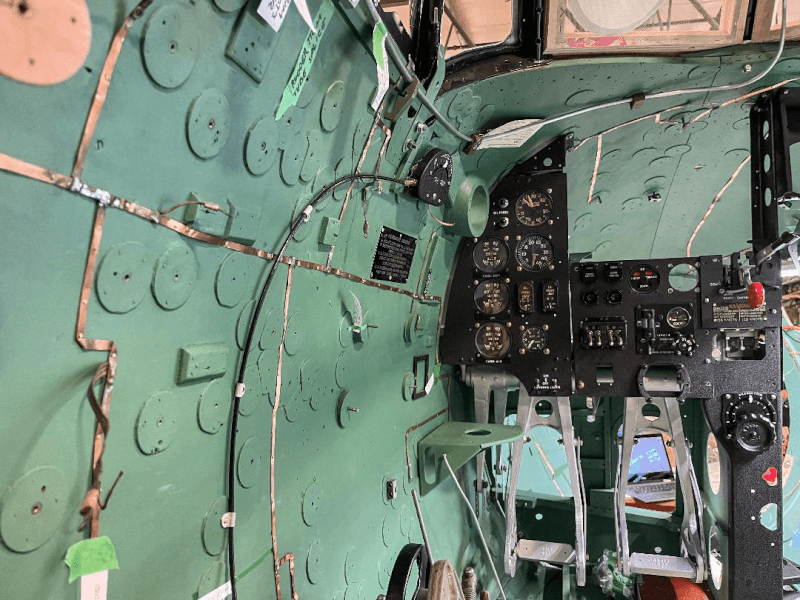

The cockpit is no ordinary cockpit, either. Because the plane is wood, there is no traditional means of grounding the electrical system. All the wiring is therefore sealed with copper tape.

But the volunteers press on, happy in their work.

The cockpit of the wooden Mosquito uses copper tape to ground its electrical wiring. [Stephen. J Thorne]

Advertisement