The troops were excited and anxious to go; on Nov. 17, there was a parade through Halifax in anticipation of the order to leave.

On Dec. 13, the downhearted men were not aboard the Canadian aircraft carrier headed to Egypt, but on a passenger train, headed back to Calgary, victims of brinkmanship diplomacy.

The canal started out as a France-Egypt partnership in the 19th century, but Egypt, beset by financial difficulties, would eventually sell its share to Britain. The canal became, and still is, a critical shipping route connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through Egypt. Egypt became dissatisfied when the financial gain brought by the canal did not outweigh the downsides of having it run through its territory.

In 1956, Egypt’s 99-year contract with the French expired. In the summer of that year, then-Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser flexed his muscles and nationalized the Suez Canal, setting off an international crisis.

The world was on the brink of nuclear war when Canadian diplomat Lester Pearson proposed a solution.

The canal was the primary route for oil from the Middle East; reduced access would almost certainly have led to economic disaster in Europe.

Britain, France and Israel sent in troops to try to regain control.

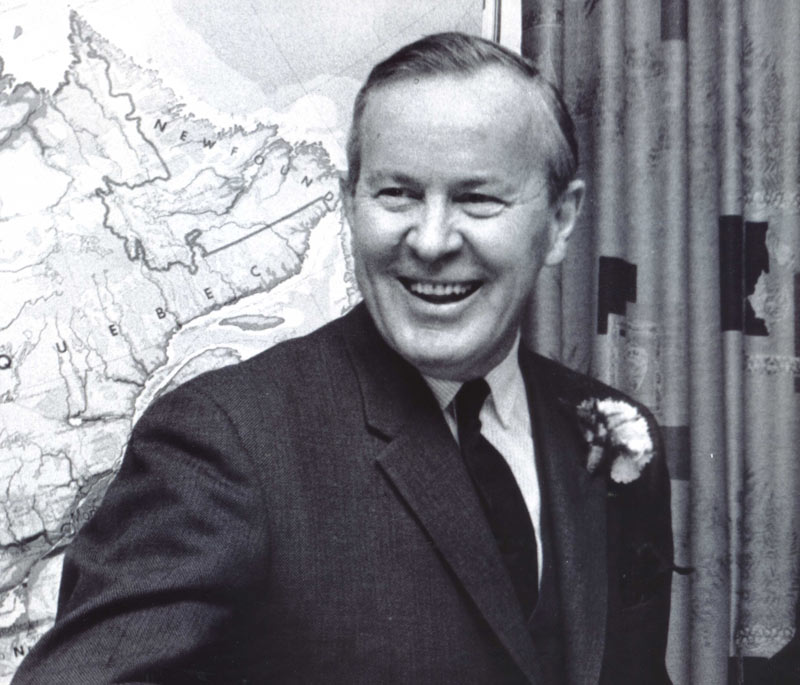

Lester B. Pearson proposed a United Nations peacekeeping force to ease tensions on the Suez Canal. [LAC/C-031796]

But Nasser again flexed his muscles, objecting, among other things, to Canada’s selection of regiment, ostensibly because its uniforms were too similar to that of British forces and its name, Queen’s Own Rifles, conjured a connection to Britain.

Since the Second World War, UN personnel were identifiable by helmets, berets, shoulder patches and armbands in the distinctive blue colour of the UN flag. These identifiers distinguish UN personnel as non-combatants and signify their neutral status. At the time, it was impossible to produce enough blue berets in advance of UN troops arriving in Egypt, but a supply of plastic helmet-liners was found and spray-painted UN blue.

It’s likely the Egyptian leader was less concerned with Canadian military fashion than the fashion in which his people perceived him—as a powerful leader.

A compromise was reached when Canada agreed to contribute only supply, transport and medical units. But it was a Canadian—General E.L.M. Burns—who commanded the first large UN peacekeeping force, about 6,000 troops from 10 countries, for the first three years.

The Canadians initially dispatched about 500 logistics personnel of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps and Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, supported by the Royal Canadian Air Force. They arrived in Egypt on Jan. 12, 1957.

Meanwhile, Canada created four units “reflecting the functional nature of the Canadian commitment,” said a CF Mission/Operation Notes report, including 56th Canadian Signal Squadron, 56 Transport Company, 56 Canadian Infantry Workshop and 56 Canadian Recce Squadron, supported by RCAF aircraft, their Canadian markings “muted or removed altogether, to be replaced by the words ‘United Nations’ on the sides of the fuselage.”Among the Canadians’ first tasks were clearing mines from the buffer zone, conducting reconnaissance, investigating violations of the agreed-upon terms, monitoring the armistice line and “maintaining a UN presence,” said the report.

By March 1957, more than 1,000 Canadians were serving in the buffer zone between the Egyptian army and French and English forces; by 1963, with tensions subdued, the number had shrunk to 780.

In 1967, Egypt flexed its muscles again and demanded UN forces leave its territory. The RCAF finished evacuating the Canadian contingent on June 1. The Six-Day War began four days later; the Suez Canal remained closed for eight years.

“Our military personnel in Egypt suffered the largest loss of life in any single Canadian peacekeeping effort, with more than 50 Canadian soldiers making the ultimate sacrifice,” said a Canadian Armed Forces news release on the 65th anniversary of the mission.

Advertisement