Evacuees line up to board a USAF C-17 Globemaster III at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul on Aug. 21. [U.S. Air Force/Senior Airman Taylor Crul]

The graveyard of empires appears to have claimed another victim. But why couldn’t a high-powered coalition that included the United States, United Kingdom and Canada defeat a radically fundamentalist group of murderous zealots?

Many said from the beginning that the post-9/11 invaders of Afghanistan were doomed to follow the Persians, Greeks, Arabs, Turks, Mongols, Britons (three times) and Soviets—none of whom managed a permanent presence or far-reaching impact in the parched and willfully independent land of deserts, mountains and open plains.

A successful campaign of liberation relies as much on winning hearts and minds as it does on strategic military successes.

Winning over Afghans, as the recent collapse of their national army suggests, was far easier said than done.

There are 14 ethnic groups in this landlocked country. Virtually none of them get along. Forty per cent are Pashtuns, who rule the southern half of the country with impunity and formed the Taliban in their ancestral home of Kandahar.

Afghanistan was once a waypoint on the Silk Road. Cities like Balkh, now a village of ancient ruins near Mazar-i-Sharif in the north, once teemed with activity, their caravanserais—combined inns, bazaars and service centres—a focal point of trade and commerce.

But Afghanistan has long since been left behind. The skills Afghans developed servicing the caravans that once passed through it are now adapted to keeping the country’s aging fleet of predominantly yellow Toyotas on the road.

Abandoned shipping containers line streets in Kabul and Kandahar, serving as makeshift shops and workshops where young boys use their nimble hands to fashion automotive parts.

The country is dirt poor and undeveloped. Yet it is rich in untapped minerals—an estimated $1 trillion worth of lithium, gold, iron, copper and gems lie under the surface undisturbed.They are now attracting the attention of China and others anxious to exploit a growing global reliance on rare-earth metals to produce consumer technology, efficient batteries, advanced military hardware and sophisticated computer chipsets. It’s hard to imagine that ever happening under a Taliban regime.

Oil, natural gas, uranium, bauxite, coal, chromium, lead, zinc, talc, sulphur, travertine, gypsum and marble are also untouched.

Afghanistan is a warrior society.

But the country has no railway. There are no ports. Its highway system is marginal, at best. There are three airports of consequence. There are roving bands of glorified bullies looking to profit from other people’s misfortune.

And then there is war.

A Canadian soldier returns fire early on Nov. 17, 2007, during an operation in the Zhari District, about 40 kilometres west of Kandahar, Afghanistan. [Cplc Robert Bottrill/Canadian Forces Combat Camera/Canadian Armed Forces]

Afghanistan is a warrior society. In many ways, it is still stuck in some century long ago. As much as Kabul is considered the centre of power, the rugged and disparate country is still dominated by warlords, each of whom controls their own districts with the muscle of their private militias.

They are skilled fighters. They know the terrain and, famously, they know how to use it.

Not long after Kabul fell on Aug. 15, local militias retook the districts of Pul e-Hesar, Bano, Deh Saleh in the northern province of Baghlan. Taliban forces won them back by Aug. 23. Taliban also gained control over Badakhshan, Takhar and Andarab close to the Panjshir Valley, where forces loyal to Ahmad Massoud, son of the late mujahedeen commander Ahmad Shah Massoud, were holding their own.

But in the greater scheme of things, there is little sense of country or nationality as we know it. Outside of Kabul, a large proportion of the population is uneducated, isolated and unworldly. They can be swayed or they can be shrewd, and many Afghans, particularly in positions of local power, played both sides masterfully throughout the 20 years the NATO coalition tried to win them over.

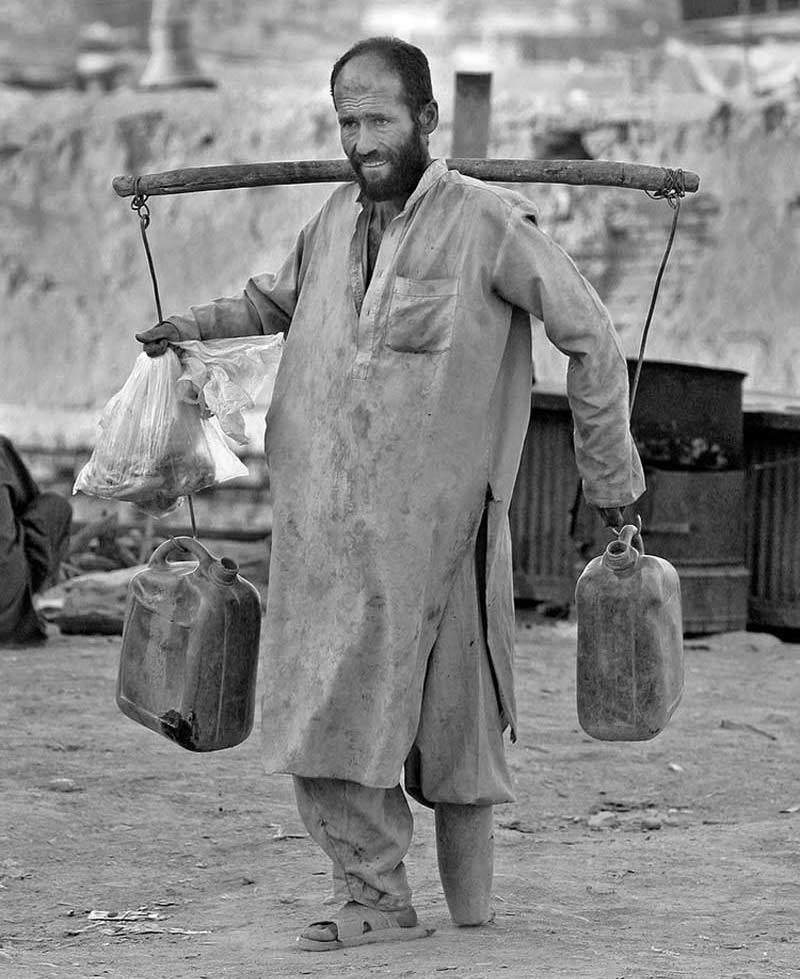

Afghans are in their sixth straight decade of war and everywhere people are simply tired, battered and beaten. Large numbers concern themselves only with securing food and water to live another day.

9/11 notwithstanding, they didn’t start this war; the West did. And the West didn’t go to Afghanistan to nation-build; it went there to kill terrorists and eradicate al-Qaida resources—the facilities where they trained, the poppy crops that financed their operations, the people who let them in, etc.It was never going to work. Loyalties were suspect. Corruption was rampant.

One can only imagine why national police withheld poppy eradication programs until after the annual harvests, going in with long sticks and lopping the heads off plants that had already been milked of their coveted opium, sometimes the day after the last of the potent liquid-turned-paste had been scooped from their billiard ball-sized bulbs.

As far as the coalition was concerned, poppy eradication was a no-win proposition. It’s tough, after all, to win hearts and minds when you’re denying farmers a crop that has at least 26 times the yield of the alternative, wheat.

The government was always corrupt. Rank-and-file soldiers and law enforcement were underpaid or often went without compensation for long periods. They were at or near the bottom of the totem pole, left to skim the dregs after various levels of leadership—some of them little more than thugs who seized on opportunity—helped themselves.The Taliban had the momentum, the weapons, the patience, the wisdom and the resources to finish this.

Police would resort to setting up impromptu checkpoints, usually at night, where they would collect money from drivers and passersby in return for passage. The practice didn’t exactly engender trust or respect in national institutions.

The perceptions were only reinforced when Afghan President Ashraf Ghani fled the country Aug. 15 with four cars and a helicopter full of cash. He reportedly had to leave some money behind because it wouldn’t fit in the aircraft.

The Taliban had the momentum, the weapons, the patience, the wisdom and the resources to finish this. They knew how it would end all along, and so did many of our troops who now mourn the plight of interpreters and other locally employed civilians left to face harsh retribution from an unforgiving enemy.

Armchair quarterbacks point to the collapse of the Afghan National Army with contempt and disdain. They have no idea of the sacrifices and suffering Afghans have endured over the past 42 years, since the costly Soviet invasion of 1979.

Since 9/11 alone, 75,000 Afghan military and police officers have been killed as a direct result of the war, along with an estimated 71,334 civilians, Fortune Magazine reported on Aug. 19. More than 3,500 coalition troops, including at least 158 Canadians, died on Afghan soil in the past two decades.For the Taliban, lives were cheap. It absorbed tens of thousands of deaths while it bided its time planting bombs, inflicting casualties, and building a new, technologically advanced army that is now using biometrics to identify people who worked with the International Security Assistance Force and the international community.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office estimates the Taliban inherited US$85 billion worth of American military hardware, including 22,174 Humvees, 42,000 pick-up trucks and SUVs, 358,530 assault rifles, 126,295 pistols and 64,363 machine guns. There are 8,000 trucks for the taking, 634 M1117 armoured vehicles, 169 armoured personnel carriers, 155 mine-proof vehicles and 162,043 radios.

Taliban fighters patrolling Kabul in a Humvee abandoned by U.S. forces on Aug. 17, 2021. [Wikimedia]

It all came a day late and a dollar short for most.

The evacuation process, long anticipated, seemed an afterthought to the government in Ottawa. It was excruciating weeks after the unfolding scenario became evident that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, already on the campaign trail for the Sept. 20 federal election, gave the military the green light to begin taking out so-called “Canadian Entitled Persons.”

Entitled, all right. As it happened, of the 3,700 people Canada is estimated to have evacuated, fewer than 15 per cent who went out aboard Canadian Globemaster aircraft are said to have been interpreters or locally employed civilians. Vast numbers never received the visas they’d been promised. An agonizingly long and complex approval process handicapped many who were contending with spotty internet access, call services and power.

An RCAF CC-177 Globemaster III with 506 evacuees aboard departs Kabul on Aug. 24. [Canadian Armed Forces]

President Joe Biden set an arbitrary Aug. 31 deadline for pulling remaining U.S. troops out and on Aug. 25 the airport was shut down to Afghans not already inside.

The rest of the NATO force went with them, almost two weeks before the previously established deadline of Sept. 11.

Stranded in Kabul and outlying areas, there is legitimate concern that many fixers, interpreters and others who worked for the Canadians will be killed, and not efficiently. The Taliban have a penchant for inflicting brutal, torturous death on essentially innocent people.

It is profoundly disheartening to many Canadian soldiers, journalists, diplomats and aid workers that the government of Canada turned its back on so many of those who risked their lives to assist its efforts in a land so far away, yet so close.

—

Stephen Thorne spent more than a year in Afghanistan covering coalition operations and Afghans’ struggles after decades of war.

Advertisement