My great-uncle William was killed in the attack on Regina Trench

Lieutenant William Edward Everett Doane of Halifax led a company in an attack on Regina Trench on Oct. 1, 1916. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Harvey Doane, my great-uncle, was a noted engineer, a celebrated yachtsman, a captivating storyteller and a veteran of the Great War. In short, he was a family icon whose name still floats and dances among us more than three decades after he died.

An elegant, old-world gentleman in a pencil moustache and yacht-club blazer, he and his wife, my Aunt Mildred, whom he called “Skinny,” used to come with Mildred’s sister, Aunt Dot, for Sunday dinners at my parents’ home in Halifax.

Wielding a loaded cigarette holder in one hand and a scotch in the other, my great-uncle would regale us.

These sessions with the senior generation of the family were generally not much fun for a young boy who was expected to dress up, sit still and keep quiet while the adults gossiped and reminisced. But Uncle Harvey was different story.

Wielding a loaded cigarette holder in one hand and a scotch in the other, my great-uncle would regale us with pre-dinner tales of his time in Egypt and Palestine with the forces of Field Marshal Edmund Allenby—he of Lawrence of Arabia fame.

Uncle Harvey never mentioned his wartime service in France; it was only recently that I discovered he was even there—and the reason why he never seemed to mention the fact.

Unknown to me, Uncle Harvey had a brother, William, who was killed at Regina Trench near Courcelette during the Battle of the Somme. He is affectionately referred to as Billie by family today, none of whom ever knew him beyond the contents of a dog-eared old album of newspaper clippings and photographs assembled by his father and eventually bequeathed to my cousin, Mary Doane.

The turn-of-the-century Doanes were a military family, of sorts. Harvey and Billie’s father, Francis William Whitney Doane, known as “FWW,” was the Halifax city engineer. Born in Barrington, N.S., he had joined the 63rd Regiment, Halifax Rifles, as a lieutenant in 1900. He went on to become captain, then quartermaster, before he was appointed honorary major in 1913.

All across the country in little towns, sprawling counties and big cities alike, militias like the 63rd had long played a fundamental role in Canada’s defence. The 63rd’s operational history from its formation in 1860 included the Fenian Raids, the North West Rebellion and the South African (Boer) War.

When not training or fighting, militias often found themselves breaking up riots, cleaning up after natural disasters and, in Halifax in 1917, helping in relief and recovery efforts after history’s biggest man-made explosion to that time devastated the city.

Troops from the Royal Field Artillery fill a water tank, filtered through a chlorinator aboard a truck. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

There were also significant social and cultural elements to militia life, with its regular get-togethers, periodic parades and refined mess dinners, says author and historian Tim Cook of the Canadian War Museum.

“The militia in a city or town tended to have the most prominent young men of society,” said Cook. “Why? Because it’s a great place to get together and network. It’s like the Rideau Club, but you are in uniform and you’re firing and engaging in manly and masculine work.

“It may look a lot like peacocking around, marching and wearing uniforms, but these people were largely integrated into the elite of society—certainly the officers. You’d be hard-pressed to find another organization that had more prominent young people in it.

“It’s very different today in the reserves, because we value military service today much differently.”

After more than 14 years of militia life, 41-year-old FWW joined the active service roster with the 219th Highland Battalion (Nova Scotia), Canadian Expeditionary Force, on Aug. 11, 1914. It was a week after Britain declared war on Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany.

His sons had followed him into the 63rd, and a year after FWW joined the 219th, Billie, the youngest by 18 months, enlisted for overseas service at Valcartier, Que.

He had a reputation as an outstanding shooter.

He had just graduated with an arts degree from Dalhousie, an athlete and “a brilliant student,” said newspaper accounts. He had his eyes set on a career in law. The fate of 22-year-old Billie, it seems, would dictate the course of his older brother Harvey’s military career.

Billie embarked for Britain aboard His Majesty’s Transport Saxonia on Oct. 18, 1915. He’d just been promoted captain with the 40th (Nova Scotia) Battalion and arrived in Plymouth, England, after an 11-day voyage.

The Cunard Line’s Royal Mail Ship Saxonia was pressed into wartime service. As HMT Saxonia, it delivered Canadian soldiers—including William Doane—to England, then served as accommodation for German prisoners of war. [The Detroit Publishing Company/Wikimedia]

He had a reputation as an outstanding shooter and by June 1916 had qualified as a 1st Class instructor in “musketry and Lewis machine gunnery.”

One of the muddiest, bloodiest trials of the war, the Battle of the Somme, was about to begin and Billie Doane wanted to be a part of it. Three days after the offensive began in disastrous fashion on July 1, 1916, with a still-unmatched 57,000 British and Empire casualties in a single day, he requested a demotion back to lieutenant in order to find a place in the fighting force. A promotion to major was pending, but if an officer wanted to see action sooner, a step back in rank was the quickest way forward to the trenches.

Billie got his demotion, but it was mid-September before he was transferred to the 25th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles) in France. On Sept. 29, he joined his unit at the front.

Two eventful days later, he lay dying in a muddy crater on the Somme battlefield near Courcelette. His last words: “I didn’t want to be hit so soon.”

On Sept. 22, the Canadians had taken the village of Courcelette, toward the northern end of the Somme battlefront. It was the first battle to use tanks and was marked by the use of the creeping barrage as an integral tactic in Allied warfare.

The measured victory (skirmishes continued for weeks after) had taken seven days and cost almost 30,000 Allied casualties. And still it continued.

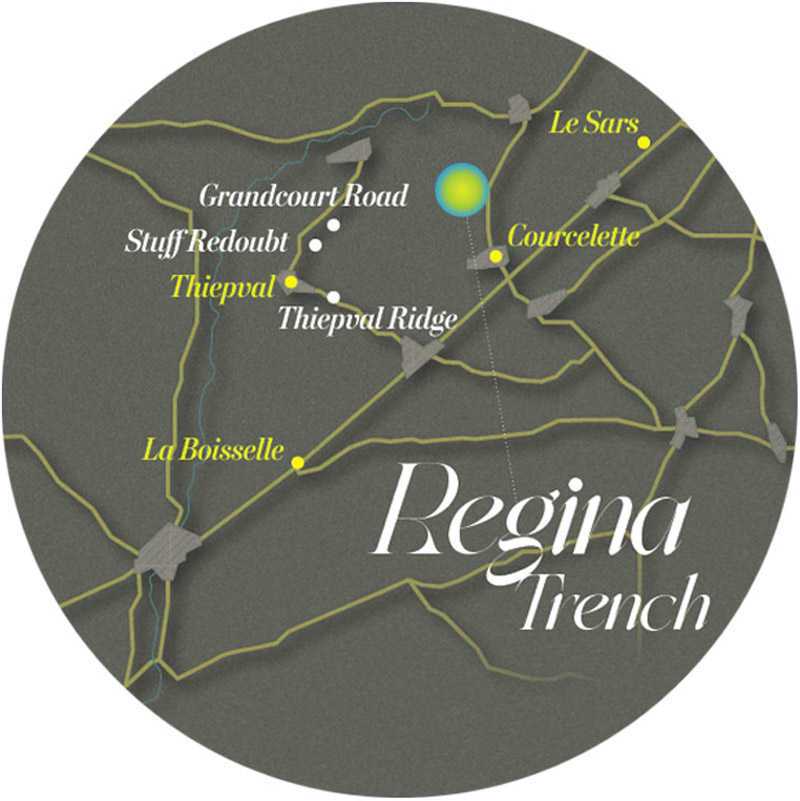

Lying north of Courcelette was Regina Trench (Staufen Riegel), a German position on the north-facing slope of Thiepval Ridge running from northwest of the village of Le Sars, southwestward to Stuff Redoubt (Staufen Feste), close to the German fortifications at Thiepval. It was the longest German trench of its type on the Western Front, and it proved a stubborn objective for the Canadians.

The preliminaries in the Battle of the Ancre Heights—Thiepval Ridge and Regina Trench—were already underway by the time Billie arrived in theatre.

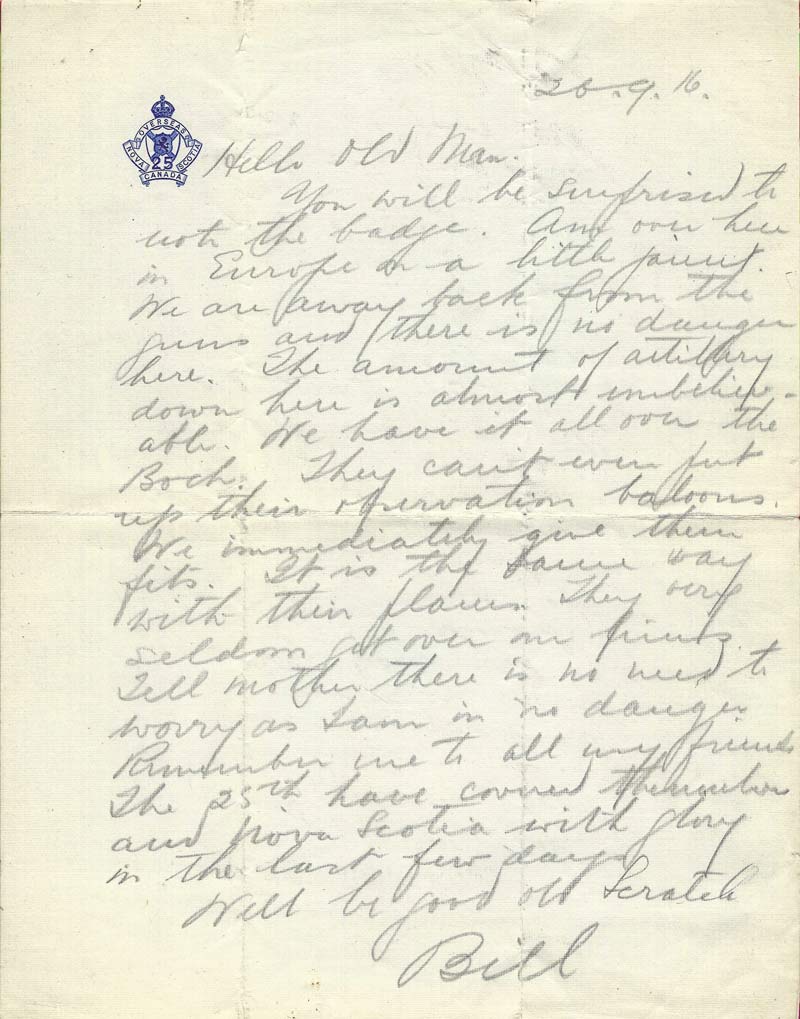

“Hello Old Man,” Billie wrote his father on 25th Battalion letterhead from the Somme. “You will be surprised to note the badge. Am over here in Europe on a little jaunt. We are away back from the guns and there is no danger here.

“The amount of artillery down here is almost unbelievable. We have it all over the Boch. They can’t even put up their observation balloons. We immediately give them fits….

“Tell mother there is no need to worry…. Remember me to all my friends. The 25th have covered themselves and all of Nova Scotia with glory in the last few days. Well, be good Old Scratch. Bill”

It was his last letter home, arriving after the Oct. 8 telegram informing his parents of his death.

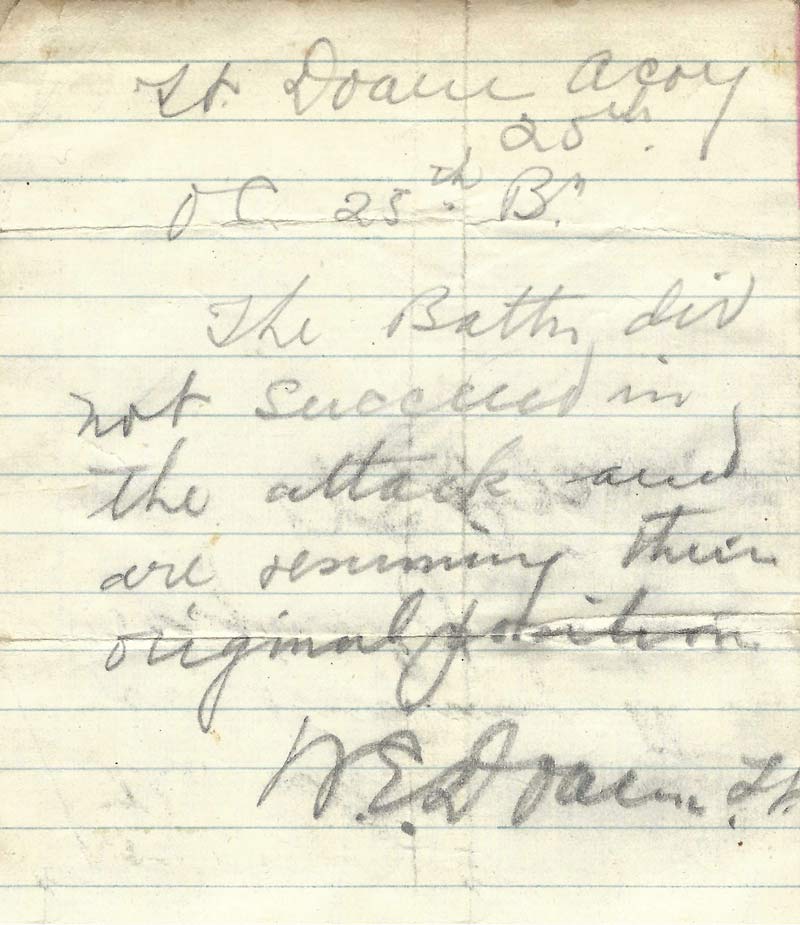

Billie’s last correspondence: a letter home on the letterhead of his adopted regiment, and his last battlefield message. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive] [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Billie Doane commanded a depleted ‘A’ Company in its attack on Regina Trench two days after arriving at the front.

The trench had been among the original Thiepval objectives, and it was supposed to have been captured by end of day on Sept. 26. But, as a Vimy Foundation history put it, “like most of the battles fought on the Somme, the attack had devolved to a multi-week slog, as the British army tried in vain to take increasingly smaller chunks of territory.”

An inscription beneath a family album photo of two soldiers inspecting a shell crater reads “Near Pozieres a ‘crump’ has landed on the Albert-Bapaume Road.” [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Just over the ridge and surrounded by kilometres of barbed wire, the meandering trench was a daunting objective. There was no way to approach it but in full view of the enemy, and there were no flanking options available. The approaches dictated a tight formation, easing the work of German gunners.

As on the first day of the Somme exactly three months earlier, Allied artillery largely failed to do its job on the Germans’ barbed-wire entanglements, and most remained intact. But British generals of the day were a stubborn lot.

Divisional commanders protested the orders to attack. The commander of the Canadian Corps, Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, took the extraordinary step of backing them up. But the British hierarchy—namely General Hubert Gough, a favourite acolyte of Field Marshal Douglas Haig—refused to reconsider.

Haig, who commanded the British Expeditionary Force, had it in his head that Thiepval could facilitate the breakout he had hoped the Somme would produce. Seeing to it was Gough’s biggest assignment to date.

By Sept. 30, fierce hand-to-hand fighting had cost the British-led forces 12,500 casualties on the ridge. Some 13 square kilometres had been gained in an advance of one to two kilometres. Zollern Trench and Hessian Trench had been taken. Regina Trench, defended by the elite German Marine Brigade, along with parts of Stuff and Schwaben redoubts, remained in German hands.

The commander of the 25th Battalion, Colonel Edward Hilliam, a native Englishman, had been told to capture Kenora and Regina trenches “at all costs.” The 25th had already seen plenty of action, and paid for it, going in.

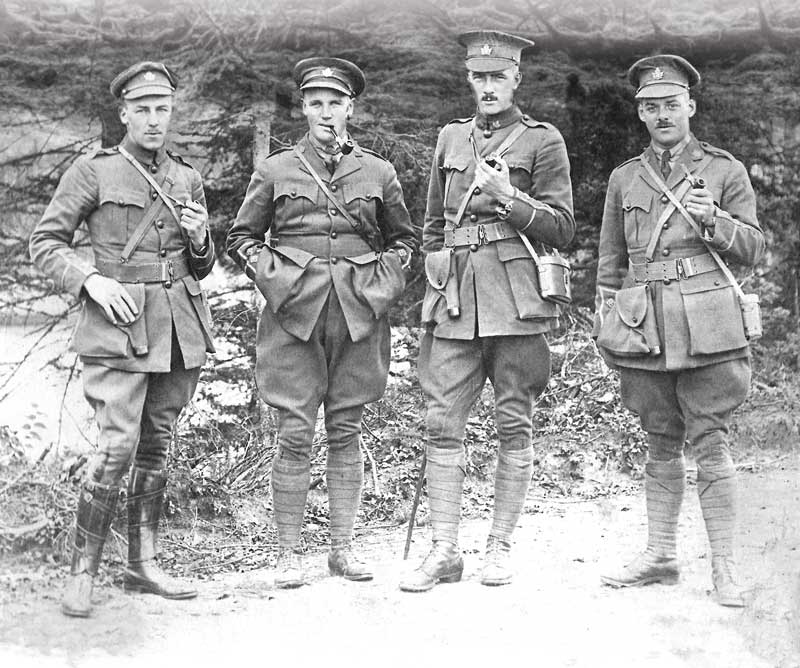

Billie Doane (at left) with Geordie Campbell, Douglas (possibly Edgar) and Scott Anderson at Valcartier, Que., before they deployed for Britain in 1915. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Nine days after the attack, Major Augustine Nutter wrote a letter to Billie’s mother on behalf of himself and Lieutenant John Harley, who was with Billie when he died and assumed command of what was left of ‘A’ Company.

Both men were recovering from wounds at the IODE Hospital for officers in London’s Hyde Park—Nutter with a bullet to his left shoulder on Sept. 19; Harley by shrapnel in the right arm at Regina Trench. He couldn’t write.

“At one time the 25th had to get out of their trenches owing to heavy shelling, but good old Bill went back three times for wounded men, and got them in,” wrote Nutter, a Montreal native. “Bill also volunteered to go out with a scouting party and reconnoitre ‘Kenora’ trench—a sporty thing to do.”

By Oct. 1, the battalion had been reduced to just 200 men with 12 machine guns, some borrowed. At most, Billie Doane’s company comprised 50-60 troops, half or less of its normal strength.

The attack on Regina Trench was launched at 3:15 p.m. in mist and light rain.

“Boom,” wrote Francis Zwicker, a private in ‘C’ Company, 25th Battalion, from Lunenburg, N.S. “A great gun from the vicinity of La Boisselle announced zero hour.

“Simultaneously every battery in [the] rear took up the signal and an avalanche of shells rent the air, crashing into enemy lines, obliterating them in fire and smoke.”

The 8th Brigade attacked across Grandcourt Road to the south with the 4th and 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles. 4CMR was to seal off Regina Trench on the extreme left to defend against German counterattacks from the west.

The 22nd Battalion (French Canadian) faced the longest trek, nearly a kilometre. It was to attack in three waves of 80 men.

Flanked by the 22nd on their right and the 24th on their left, Billie was to lead his company up the middle with the rest of the 25th, part of a kilometre-wide attack that would cross Kenora Trench and press on into Regina.

“The thin khaki line comprising ‘A’ Company and two platoons of ‘C’ sprang from their trenches,” wrote Zwicker, who watched as they ran past the small advance trench in which his platoon had spent four weary days, 100 metres in front of the main line.

A purple Very light rose from the German lines, signalling “enemy advancing, artillery assistance required.”

A barrage ensued and the Canadians were raked with heavy machine-gun fire, “speeding little messengers of death into our ranks,” as Zwicker described it in The [Halifax] Sunday Leader. “The Grim Reaper had already been busy.”

Troops inspect a captured German Mauser T-Gewehr anti-tank rifle. Some 15,800 of the 13-millimetre guns were produced, the only weapon of its kind in the war. The inscription in the family photo album says it “could pierce any spot on a tank—but only 1 out of every 10 were fired—Hinie hadn’t the nerve at the last.” Heinie, short for Heinrich, is a derogatory term for German soldiers that originated in the war. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

A sergeant-major paused and ordered Zwicker’s platoon forward.

“On we rushed through the smoke of battle; the noise of bursting shells, the rattle of rifles and machine guns seemed one continuous explosion, which made the ground sway and tremble under our feet, and the air about us vibrate.”

The 22nd made it a half-kilometre before artillery and small-arms fire slowed it to a crawl and its troops realized that the defensive wire had not been touched.

One company was virtually eliminated between the enemy trenches. Part of another reached Regina Trench but was overwhelmed and destroyed.

Only 30 members of the 25th reached the wire at Regina, Billie among them. At some point, he pencilled a last message: “The Battalion did not succeed in the attack and are resuming their original position, W.E. Doane, Lt.”

Harley said Billie was just 15 metres from the German line when he was cut down. The Liverpool, N.S., native was with his comrade when he was hit. Harley dragged his wounded company commander into a shell hole and bandaged him, but Billie died a short time after, “without much pain.”

“He knew he was hit badly,” Harley reported, “and all he said was, ‘I didn’t want to be hit so soon.’”

Harley removed the dead man’s watch and, via Nutter, promised Billie’s mother he would hand it to her soon. Harley returned to Halifax for treatment, where it is believed he made good on his promise. Plagued by nerve damage to his right arm, he never returned to the front. But he lived another 50 years.

The left forward company of 5CMR made their objective and established a blocking position at the west end of Regina Trench, but it was driven out early the next morning by multiple counterattacks. Another assault company was impeded by wire and machine-gun fire and reported only 15 survivors.

They took cover in craters and ditches and waited for nightfall before scurrying back to Kenora Trench, where the follow-up company had secured a stretch to within about 100 metres of the junction with the main position.

In his after-action report, Hilliam said 30 of his men who reached the wire dug in and remained in shell holes until dark. “Lieut. Gray who was in charge, tried to collect them together. Finding only six left, he decided to fall back on KENORA.”

Three soldiers, including a Corporal Newton of ‘B’ Company, were stranded forward and took refuge in a shell hole to the right of the German trench. They stayed there until 3 p.m. on Oct. 3, when Newton led his two men out, losing one in the process.

The 25th suffered 112 casualties in the advance, including 46 dead or missing. It pulled out of the Somme on the night of Oct. 1-2, heading west and north to Lens before relocating four months later to the Vimy region, where it would participate in the seminal victory at Vimy Ridge the following spring.

A week after Billie died, FWW and Alice Doane received the dreaded telegram: “Regret to inform you that your son William has been killed in action, nobly doing his duty for his country.”

Unaware of his brother’s fate, Harvey had married Mildred on Oct. 6. The couple were on their honeymoon when the bad news came. Billie’s death was all over the local papers, and letters and tributes continued to come in.

“It was Bill’s first tour in the trenches and I watched him closely,” wrote Lieut. Roderick C. MacDonald. “He was cool and collected as an old hand, fearless and energetic and at once won the admiration of the men.

“I hope that if it is my lot to die in France, I can die as nobly as Bill did.”

“Many a man has spoken to me of the way he led them in that charge and how well he was leading and encouraging them when he was hit. I know your sorrow will be mingled with pride that he did his part in the great work allotted to him.

“I myself will always think of him as an old friend and a brave soldier and only hope that if it is my lot to die in France, I can die as nobly as Bill did.”

He didn’t have to. MacDonald was promoted to captain and survived the war, albeit with a case of tuberculosis.

The fighting for Regina Trench continued through October and into November. On Oct. 21, the 4th Canadian Division captured the western portion of the trench with little opposition while, farther west, two divisions of II Corps took Stuff Trench in 30 minutes. The gains gave the Allies control of Thiepval Ridge.

The Canadians repulsed three counterattacks the next day. Over the two days, they took more than 1,000 German prisoners. The 4th finally captured the east end of the trench during the night of Nov. 10-11.

Canadian losses during some 42 days of fighting for Regina Trench totalled 14,207. There would be no breakout at the Somme.

The battle north of Courcelette was raging when a bereaved FWW headed for England on Oct. 13 aboard SS Olympic, sister ship to the ill-fated RMS Titanic.

He was appointed quartermaster of the 17th Reserve Battalion and spent nine days in France in November 1917 on “conducting duties,” during which he visited his son’s battlefield grave.

Billie’s battlefield grave, the earth still freshly turned. The inscription reads: “Lnt W.E.E. Doane 40th Canadian Inf. Killed in action 1.10.16. Next of kin F.W.W. Doane, Halifax Canada.” [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive]

Uncle Harvey joined the active roster on Oct. 16, 1916, and went to England with the Canadian Reserve Artillery the following March. As a major, he was assigned to the 420th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery, part of Britain’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

He was later seconded for duty with the War Office and finished his overseas service with the 420th in France. He returned to Canada aboard SS Scotian, arriving home on March 3, 1919, full of stories.

Advertisement