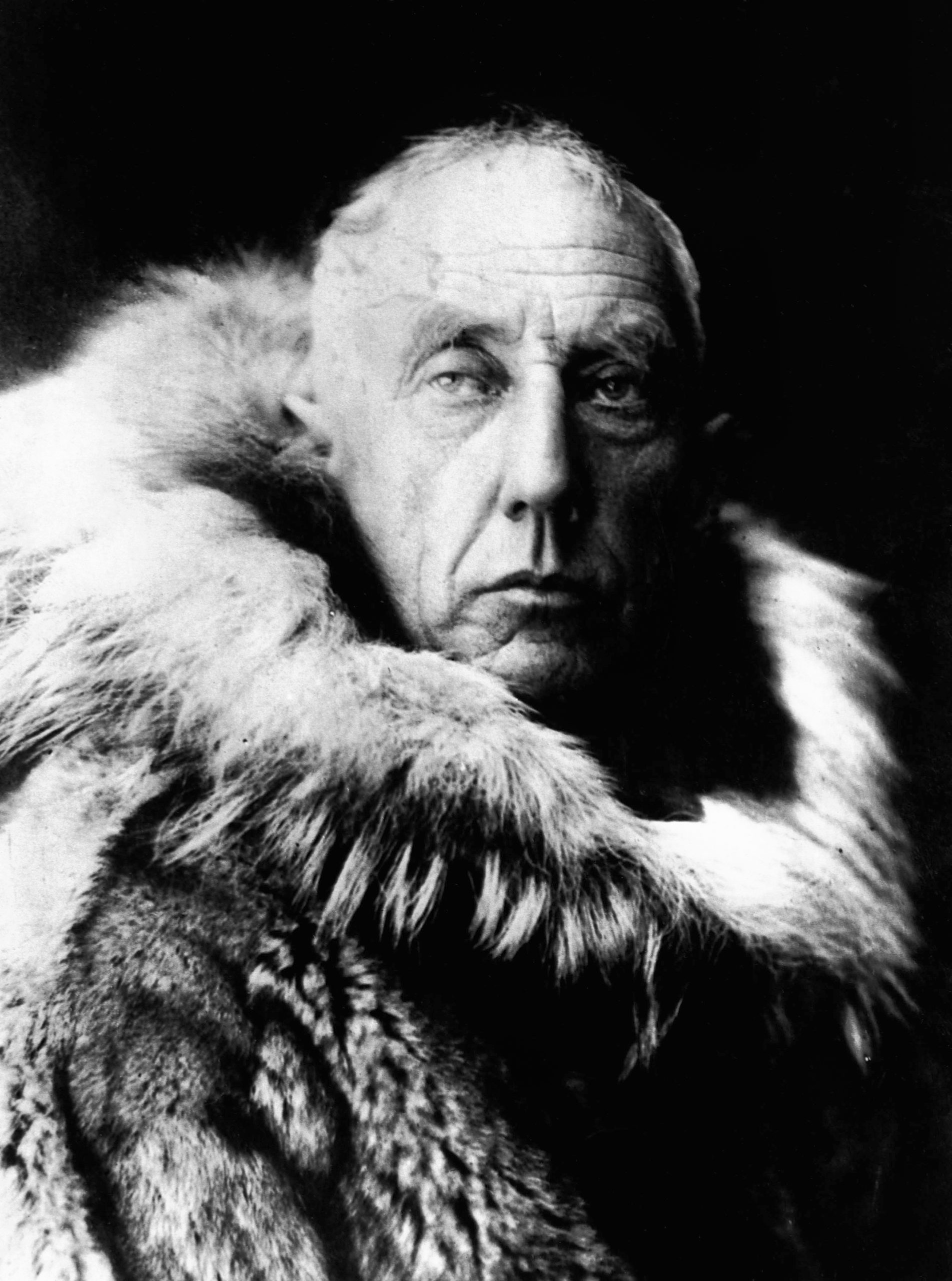

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and a crew of six navigated the Northwest Passage, reaching the Bering Strait in 1906. [Wikipedia]

On June 16, 1903, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and a crew of six left home waters in a herring boat names Gjøa to sail to Canada in search of a way to the Pacific Ocean through the Arctic Ocean across Northern Canada. He was the first to navigate the Northwest Passage through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, reaching the Bering Strait in 1906.

The feat was welcomed by merchants, traders and governments on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The passage could cut 7,000 kilometres off the trade route from the west to east coasts of North America via the Panama Canal.

But for the next century, ice made the route unfeasible. In 2007, the passage was temporarily ice-free for the first time. Merchants began pressuring to develop the passage for routine cargo transport between Asia and Europe.

From left: Gustav Juel Wiik, Roald Amundsen, Peder Ristvedt and Anton Lund relax on the deck of Gjøa while crossing the Northwest Passage. [Fram Museum]

The United States, the European Union and China argue the passage is an international strait, and they have the right of transit for peaceful use. They argue Canada can enact laws to control fishing and smuggling and to protect the environment, but it does not have the right to close the passage.

The United States has long tested and flouted Canada’s claim. In 1969, it refused to ask Canadian permission when it sent an oil tanker, accompanied by a U.S. Coast Guard vessel, to test viability of shipping oil from Alaska to the Eastern seaboard.

In 1985, a U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker traversed the passage from Greenland to Alaska. The U.S. government said they neither asked, nor were legally required to ask, Canada’s permission. That year the federal government passed the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act, establishing Canada’s role in Arctic environmental protection.

In 1988, the two governments signed the Arctic Cooperation Agreement, which relieved the tension, but didn’t settle the sovereignty issue. In 1996, Canada signed the Ottawa Declaration to protect the Arctic and establish co-operation between Arctic nations.

In 2005, the U.S. navy released photos of one of its submarines surfaced at the North Pole—reached by travelling the passage, and without informing Canada (as have Russian submarines, covertly).

“You don’t defend national sovereignty with flags, cheap election rhetoric or advertising campaigns,” said then Prime Minister Stephen Harper. “You need forces on the ground, ships in the sea, and proper surveillance.”

All branches of the military and many federal government departments, including the RCMP, are involved in enforcing Canada’s Arctic sovereignty.

On the ground are the Canadian Rangers, who do regular patrols. Canadian Forces Station Alert is staffed year-round and there are four Arctic Response Company Groups, as well as regular Arctic army training at a permanent base.

The USS Toledo arrives at Ice Camp Seadragon in the Arctic Ocean, kicking off Ice Exercise 2020, a three-week biennial exercise conducted by the U.S. Navy and allied forces including Canada. [Michael B. Zingaro / U.S. Navy]

The RCMP has had a presence in the Arctic since the late 19th century, enforcing Canadian law in the North by dog sled, snowmobile and aircraft. It has 59 detachments in the North, 11 of which are in communities accessible only by aircraft.

For now, weather and geography continue to inhibit commercial traffic in the Arctic. Nights are long, there are shallow areas and shifting sand bars. Ice can be a danger even in summer. Environmental incidents are a risk—and insurance is costly.

But eventually, climate change will cause more conflict. Canada is standing guard.

Canadian Ranger Scot King, of 1 Canadian Ranger Patrol Group, participates in weapons drill lessons as a part of a national Canadian Ranger Basic Military Indoctrination pilot course held in the training areas of the Farnham Garrison in Farnham, Quebec on April 13, 2016.

Advertisement