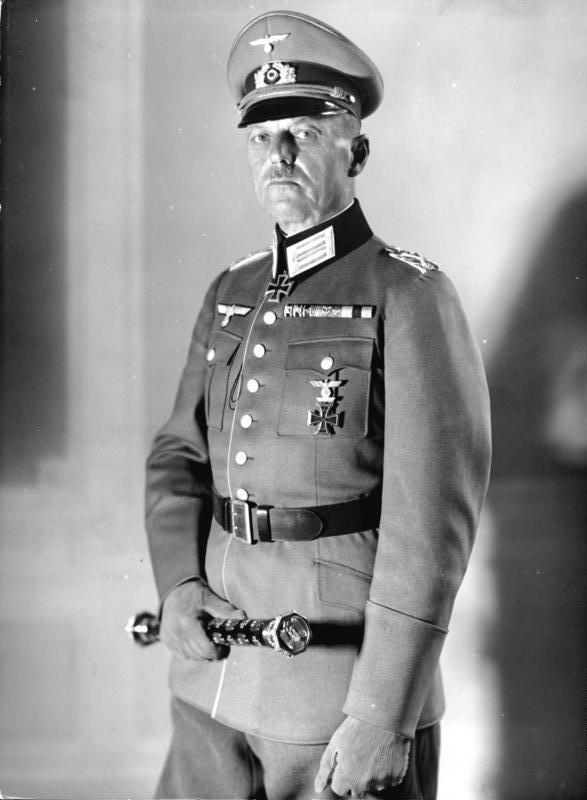

Field Marshal Karl R. Gerd von Rundstedt in 1940. [Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L08129 / CC-BY-SA 3.0]

A field report submitted by Adolf Hitler’s commander-in-chief on the western front said the Allies’ invading D-Day forces gained a foothold in occupied Europe due to four key factors. In the report filed two weeks after the June 6, 1944, invasion, Field Marshal Karl R. Gerd von Rundstedt said the Allies’ “complete mastery in the air” was the No. 1 contributor to their early successes in Normandy.

Von Rundstedt also cited “the skilful and large-scale employment of enemy parachute and airborne troops [and] the flexible and well-directed support of the land troops by ships’ artillery” as major factors in the invasion, along with painstaking preparation and a swift post-invasion buildup.

“Opposed to this stands the quality of the German soldier, his steadfastness and his unqualified will to fight to the last with army, navy and air force,” von Rundstedt wrote. “All three branches of the service have given their best and will continue to give it.”

While the report criticized elements of the Allied attack and exaggerated the effectiveness of German defences, the field marshal must have seen the writing on the wall.

By the time von Rundstedt had written his chin-up, stiff-upper-lip report, some 156,000 Allied troops had landed along 80 kilometres of French coast—24,000 by air and the rest by sea.

A storm was still raging in the English Channel, creating havoc at the Allies’ artificial ports of Arromanches and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. Many small boats would run aground or sink before good weather moved in.

Allied military operations had slowed to allow resupply to catch up, but the move inland continued. Aerial bombing of German forces was unabated. Hard street fighting was taking place in Valognes. German troops were abandoning positions to join in the defence of Cherbourg; the German generals would soon be reconsidering their hold on Caen.

“The German military leaders in Normandy were now becoming despondent,” said the official history of the Canadian army in Europe,” noting Hitler had come to France and conferred with von Rundstedt and Erwin Rommel at Margival near Soissons on June 17. “This meeting was inconclusive.”

“It appears that Rommel counselled a counter-offensive to be preceded by a limited withdrawal to enable the battle to be fought outside the range of Allied naval guns; but there was no decision, except that Hitler authorized “small adjustments in the front line’ of the 1st S.S. Panzer Corps.”

Within 10 days of von Rundstedt’s report, however, the Allies were in firm control of Normandy. Two months later, Paris was liberated.

In his 3,100-word assessment, the field marshal described how “the proximity of the English mother country and thus also of all the embarkation and supply bases afforded to the Anglo-Saxons in their first great land attack against [France] the opportunity of employment on the greatest scale so far of men, material and technical means.

“Systematic, almost scientifically conducted preparations in all fields for this attack were rendered more easy in every respect by a far-reaching network of agents in the occupied area of the west.”

The document was intended to be passed on “as the subject of instruction and drill in all fronts not yet attacked.”

“The enemy had hoped to be able to surprise us. He did not succeed,” von Rundstedt unabashedly declared, adding the airborne landings were “no surprise, since our own command and troops had counted on them for weeks.

“Thus the enemy parachute and airborne troops suffered heavy—and in parts even extremely bloody—losses, and were in most places annihilated in the course of the battle. They did not succeed in breaking up the coastal defense from the rear.”

The point of the airborne drops, he seems to have missed or ignored, was to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the front—which the Allied paratroopers did, in spades.

“The technique and tactics of the enemy airborne forces are highly developed,” von Rundstedt acknowledged. “Training for battle was also on a high level—tough fighters, skilled in adapting themselves to the terrain!”

Von Rundstedt, Werner von Fritsch and Werner von Blomberg, attend a memorial service, Unter den Linden, Berlin 1934. [Wikimedia]

“This was recognized weeks before the actual landing by trial landings carried out in England,” he wrote. “The enemy could thus discover gaps in the rows of underwater obstacles along the beach, by-pass the obstacles with his tanks, and for the rest open up passages and overcome in part these beach obstacles.

“Where these obstacles were not discovered because they were under water, heavy enemy losses in landing craft and in men resulted. But obstacles on the dry beaches also noticeably delayed the tempo of the landing and consequently increased the enemy’s losses by our fire.”

The landings were fully visible to the German defences, he added, and tipped off by heavy bombardment “of extraordinary intensity from the sea and the air, with weapons of all calibers.”

The result was that field defences were “more or less” knocked out and “ploughed down,” with only the solid fortifications remaining intact in most cases.

“The enemy seeped in through the gaps without trying to attack the fortifications and big strong points. These strong points held out in cases for over a week and therefore split up enemy forces.

“By holding out to the last they helped their own leaders very much to gain time and to prevent a breakthrough of the enemy from the bridgehead.”

Von Rundstedt said Allied air forces were “almost unlimited in radius,” controlling in numbers not only the main battlefield but also roadways up to 200 kilometres inland.“Moreover, the enemy carries the battle right into the home-battlefront with his tactical bombers, in order to destroy the large railway systems, especially railway junctions, marshalling yards, locomotive shops, bridges and important works connected with the war industry.

“Notwithstanding the highly developed railway system and the numerous good main and secondary roads, the enemy succeeded by attacking in force and uninterruptedly with his air force to interrupt supplies and replacements and cause so many casualties in rolling stock and motorized columns that supply and replacements have become a very serious problem.”

The field marshal dubbed low-level strafing attacks “road-chasing,” and said the nearer the battle area, the more frequently appeared the fighters and bombers.

“By their attacks, they interrupt all major movements in good weather by day and by using flares at night. The emphasis of the enemy air attacks lay at first on the main highways but now they are attacking every form of movement.”

He said 29,000 Allied sorties were counted in two-and-a-half days, as deep as 65 miles from the enemy bridgehead. “Of these, about 2,300 aircraft a day dive-bomb and strafe every movement on the ground, even a single soldier.”

He warned commanders that wireless stations were located too close to command posts, and should be moved far enough away that “the post is not covered in the bombsight or by sticks of bombs.”

He said railroad transport could not get much closer than 200-250 kilometres from the front and scheduling was impossible.

“Marches by day are obviously excluded in good weather. The short summer nights must be used from dusk to the morning shooting light for exact reconnoitering of streets and crossings, for the preparation of smooth engagements, for quick marching in loose formation, for avoiding main streets and smoothly seeping into the rest areas where reconnoitering has been carried on.

“The troops must constantly be prepared for low flying attacks.”

He stressed the importance of maps and acquisition of reliable guides to help German troops navigate unanticipated movements.

“Street commanders are to be appointed to watch over all the traffic from and to the front. Circuitous routes around villages are to be mapped out and to be posted with signs.

He ordered the appointment of engineer officers to supervise road repairs and he emphasized the importance of camouflage.

“Troop and column leaders must know that once a unit or column has been discovered by enemy aircraft it will be attacked from the air until put completely out of action…. There is always need for camouflage adapted to the terrain.”

Von Rundstedt said Allied naval guns had rendered “the movement of tanks by day, in open country” impossible.

“Strict control of the population must be exercised,” he wrote. “Suspicious persons, especially young men with ‘small suitcases,’ may have arrived secretly.

“Whoever does not belong in a particular place, whoever cannot give a clear account of the destination and the purpose of his wanderings, should be arrested and delivered to the labor forces.”

He stressed the importance of communication but said the use of wire connections in the battle area is futile. He cited “the cyclist, the motorcycle messenger, the officer in the sidecar or in the light armored car, and for short distances the runner” as the most reliable means of transmitting messages.

Rommel and von Rundstedt met with Hitler again at his mountain retreat, Berchtesgaden, on June 29. It was nine days after von Rundstedt filed his report.

The Canadian army account said the two persuaded Hitler reluctantly to abandon his “cherished project of a major offensive directed on Cherbourg to recover the great port and split the Allied bridgehead.”

“But it is evident,” added the account, “that he was unwilling to accept the generals’ opinion that the existing line in Normandy had become untenable.”

It was at this time, von Rundstedt later told Canadian interrogators, that he had a telephone conversation with Hitler’s armed forces chief, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel.

“What shall we do?” Keitel asked him.

“Make peace, you idiots!” was von Rundstedt’s reply. “What else can you do?”

“It is not surprising that changes in the command followed,” concluded the Canadian army history. “Making peace was not a practical policy for Hitler.”

Von Rundstedt was dismissed from duty, though the official announcement attributed his departure on July 4 to age and ill-health. Hitler wrote him a cordial letter, and awarded him Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross.

Von Rundstedt would serve four years in prison after the war but, in failing health, he was declared unfit to stand trial on war-crimes charges. He was freed by his British captors in 1949 at age 73, frail with no home, his bank accounts frozen, and no income. He eventually received a military pension from the West German government.

Karl R. Gerd von Rundstedt died of heart failure on Feb. 24, 1953. He was 77.

Advertisement