– Illustration by Robert Carter –

Five years after the Canadian military lowered the flag for the last time in Afghanistan, the first war in which post-traumatic stress injury was recognized as a war wound, it seems impossible to determine how much the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and related mental-health conditions have added to the cost of the war.

The sum of mental-health damage in human terms—of lives lost through suicide, potential lost, marriages and childhoods irrevocably damaged—can’t be calculated, except to say the toll has been astronomical on affected veterans and their families.

And neither does it seem possible to fix a financial price tag for what has already been paid or a final tally, because some costs will continue decades into the future. Medical services and financial support will stretch over the lifetimes of some veterans with Afghanistan-related psychological wounds.

Neither the Canadian Armed Forces nor Veterans Affairs Canada can supply a specific dollar amount for mental-health services they provide to veterans of Afghanistan.

“We don’t necessarily subsect it out,” said Jennifer Eckersley of CAF Health Services Group. “It’s not ‘this person came to us for this reason because of Afghanistan or Bosnia.’ We provide health care to our entire population regardless of causal factor.”

But between 2014 (the year Canada’s Afghanistan mission ended) and 2017-18, the federal government had to top up the military’s disability insurance plan several times to a total of more than $1.2 billion. Federal Supplementary Estimates for 2017-18 said that year’s increase was due to “a significantly higher number of claims, largely owing to increased awareness and recognition of PTSD and mental health.”

Some of that additional amount would go to cases from service unrelated to Afghanistan and conditions other than mental health. But the top-ups coincide with the period when most affected troops would be expected to report post-traumatic stress injuries from the punishing combat experiences in the 2006-11 operations in Kandahar. In 2008, it was reported that about 28 per cent of troops who served in such high-threat locations were diagnosed with PTSD. The median delay in seeking PTSD treatment is about seven years.

Not everyone who experiences trauma develops PTSD, but a CAF study that followed 30,513 Afghanistan veterans deployed before 2009 found that 13.15 per cent had a mental-health disorder (and eight per cent had PTSD) attributed to their service there. A 2016 PTSD backgrounder reported that 11.1 per cent of regular-force personnel meet criteria for PTSD diagnoses some time in their lives.

Over five years ending in 2018, there was a 56 per cent increase—from 1,600 to 2,500—in applications to the Service Income Security Insurance Plan, which provides short-term financial support for medically releasing CAF personnel transferring to VAC (and for some disabled veterans to age 65). Treasury Board said the increase in claims was due to increasing awareness of mental-health issues and greater numbers of medical releases. To prevent future shortfalls, projections are now based on a baseline of 2,500 annual claims, said Treasury Board spokesman Martin Potvin.

“I would say it’s reasonable to think that we’ve reached the peak,” said Colonel Rakesh Jetly, CAF chief psychiatrist, one of his several roles in mental-health leadership. “But cases will continue to come forward for years.”

Although VAC does keep track of the number of Afghanistan veterans it serves, “we are unable to provide a financial figure that corresponds to this number,” said VAC spokesperson Emily Gauthier.

Just over 40,000 CAF regular and reserve force and RCMP members served in Afghanistan. In 2017-18, VAC served 16,432 Afghanistan veterans, of which 10,551 received disability awards and benefits related to that service, 5,598 with PTSD and 6,732 for mental-health conditions (some veterans are in both categories). That’s up from 8,945 Afghanistan veterans in 2012-13, of which 5,427 were receiving disability benefits and awards.

VAC tracks expenditures by program, not by health condition, explained Gauthier. “We track expenditures based on, for example, disability awards, but we do not capture the expenditure associated with the individual mental- or physical-health condition associated with that award…. Many of VAC’s programs have a mental-health component, and…the cost of these components cannot be isolated,” said Gauthier.

“It is important to note that regardless of the forecast, every eligible veteran who is entitled to a benefit will be able to take advantage of it, whether 10 or 10,000 veterans come forward,” she said.

Nor is the department able to forecast a rise or drop in mental-health costs attributable to service in Afghanistan, since forecasts are also program-based. “VAC does not forecast by specific medical condition such as PTSD,” said Gauthier, nor by special duty area or operation, mission or conflict.

While a mental-health component cannot be broken out, the amount spent on disability awards, better known as lump-sum payments, to veterans serving since 2006 rose to $1.62 billion in 2017-2018, from $472.6 million in 2014-15. Again, while not all those payments would be for mental-health concerns, the growth coincides with the time Afghanistan veterans would be reporting them. The 2014 report Mental Health of the Canadian Armed Forces notes that 18.9 per cent of regular force members who deployed to Afghanistan had reported at least one mental-health disorder in the previous year.

Adding to the confusion, no one knows how many veterans, undiagnosed or by preference, are soldiering on outside of the military- and veteran-support systems, relying on provincial health programs and personal finances to cover treatment and therapy.

The cost of war is devilishly difficult to determine, even in the United States, which has researchers and health economists dedicated to the subject. “The vast scale of military spending…makes it practically impossible for anyone to have a comprehensive understanding of the topic,” wrote Steven Aftergood, director of a Federation of American Scientists project on government secrecy.

There is much debate about what to count as a cost of war and how to make projections about future costs. In many countries, veterans’ disability compensation is calculated on severity of the wound, illness or injury and how much of it is related to service. But it is an evolving calculation. Post-traumatic stress injury has only recently been counted as a cost; research now shows that military service exacerbates other health conditions. And now questions are being raised about how much can be attributed to pre-service experiences and even genetic makeup.

What is known is that the cost of health care for disabled veterans accumulates for decades after a war. “The evidence from previous wars shows that the cost of caring for war veterans rises for several decades and peaks in 30-40 years or more after a conflict,” wrote Linda J. Bilmes of Harvard University in her 2011 report Current and Projected Future Costs of Caring for [U.S.] Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan War. In the U.S., spending on benefits for First World War veterans peaked in 1965, then began the slow decline as the Great War generation died.

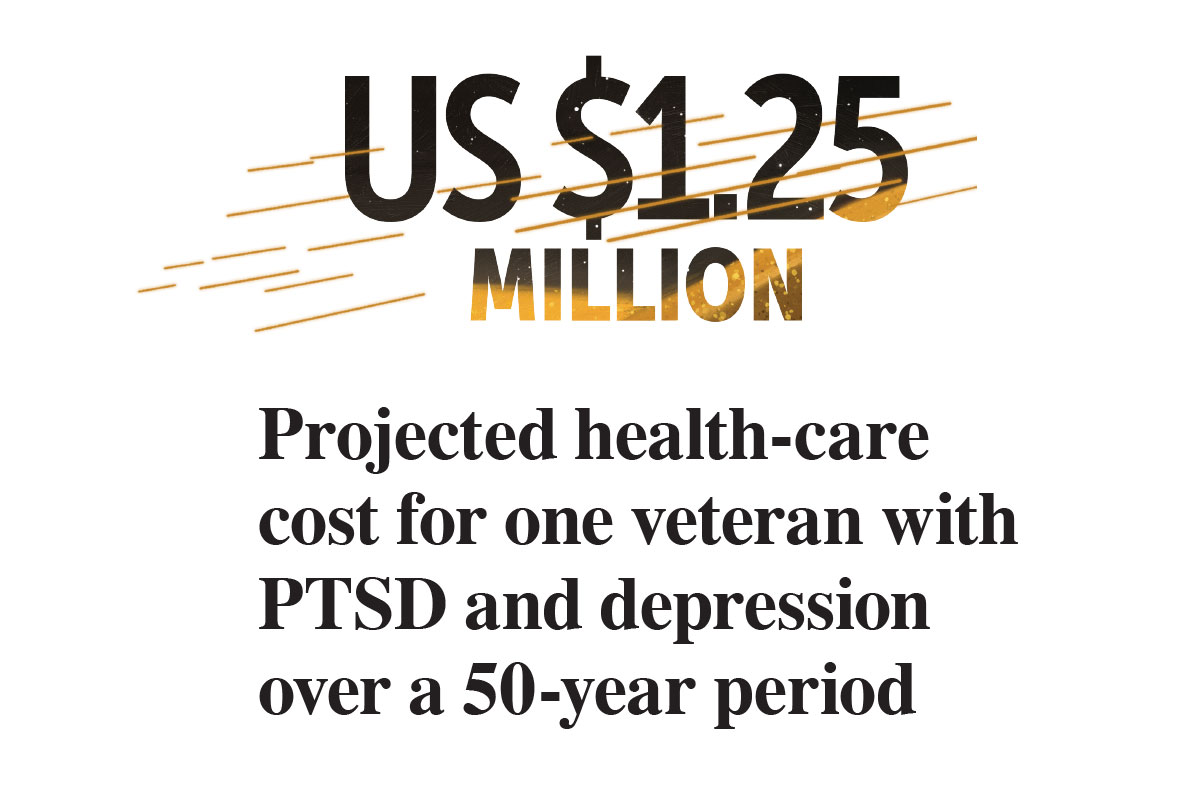

The American think tank RAND Corporation’s Invisible Wounds of War report estimated two-year costs for treatment for one U.S. service member with PTSD ranges from $5,904 to $10,298, and for depression from $15,461 to $25,757. A 2012 article in Military Medicine by health economists projected the cost of caring for one veteran with PTSD and depression as US$1.25 million over 50 years—not counting other health problems, and perhaps twice as much for a veteran with traumatic brain injury.

North of the border, with a smaller military and smaller pool of researchers, there is much less debate.

A Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO)report in 2015 estimated that the cost of providing financial support to Afghanistan veterans would total $157 million between 2015 and 2025, discounting (in part due to lack of data) health care, pharmaceuticals and rehabilitation services. It estimated that providing disability benefits to Canadian combat veterans for a single year of military operations would likely cost $145.2 million over nine years.

“However, the costs would continue to accumulate for decades….” Veterans with mental-health issues “typically require greater resources over time than do their peers,” the report said.

Research shows that PTSD raises the risk of developing other health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, suicide, depression or substance abuse. It also compounds chronic conditions related to aging.

Although they make up only 18 per cent of disabled veterans, said the PBO report, Afghanistan veterans are three times more likely to have a mental-health diagnosis. They are also 20 years younger, on average, than other disabled veterans and will collect benefits longer. The report predicted that by 2017 benefits paid to veterans with mental-health conditions would exceed those of veterans with musculoskeletal conditions.

Given all these factors, it may well be impossible to figure out how much mental-health treatment contributes to the cost of war.

Former Veterans Ombudsman Guy Parent addressed the issue in his blog in 2014. When allocating funding for the Afghanistan mission, did the government “consider fully the ‘life-cycle’ cost of the mission, including the impact on veterans’ care needs? Allocating the necessary funding to ensure proper rehabilitation and transition to civilian life of the mission’s potential casualties would not only have been a sound investment in veterans, but one that will benefit Canada in the long run,” he said.

Veterans’ needs, he said, should be “an integral part of the national security continuum.” Not an afterthought.

But prior to Afghanistan, who could have known what the mental costs would be, when recognition of mental-health injuries was so new, and no one could predict, based on data then available, just how many troops were likely to be affected?

If the mental-health cost of the Afghanistan war is incalculable, what we do know is this: war leaves a trail lined with gold and etched in pain.

If mental health was part of the collateral damage of the Afghanistan War, support for mental-health injury is a collateral benefit. The Canadian Armed Forces now has a much more robust mental-health care system.

“Someone once said that one of the few winners in war is medicine,” said CAF chief psychiatrist Colonel Rakesh Jetly. “The First World War gave us plastic surgery. The concept of triage, surgical advances, penicillin, use of blood products and antibiotics, urgent evacuations—all these were from the First World War, the Second Word War, Korea and Vietnam.”

The war in Afghanistan spurred improvements in prostheses and amputee care, better ways to treat blood loss and trauma on the battlefield, better understanding of physical brain injury—and wide acceptance of psychological injuries as war wounds.

Post-traumatic stress disorder has been a part of military life as long as there have been wars, but it was only given a medical diagnostic description in 1980. After that, thousands of Canadian military personnel—from missions in Somalia, Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia to those who experienced other traumas such as vehicle accidents, sexual assault, recovery of bodies from the crash of Swissair Flight 111—have been diagnosed with PTSD.

But it was the military conflicts of the 1990s that made it obvious that military psychological injuries needed to be more fully addressed in Canada. The Croatia Board of Inquiry reported that stress-related injuries were three times higher among deployed personnel than civilians, spurring changes in both the defence and veterans’ affairs departments.

Major Stéphane Grenier, himself struggling with post-traumatic stress injury and suicidal thoughts, produced a video in 1998 about the traumatic CAF experiences in Rwanda, where peacekeepers were helpless witnesses to genocide and there was no peace to keep. He was subsequently tasked to explore solutions to address the resulting anguish.

In 2001, the year Canada went to war in Afghanistan, Grenier coined the term operational stress injury (OSI). What followed was a seismic shift in the military view of mental health, putting mental injuries on the same footing as physical injuries.

OSI encompasses a range of mental conditions, including post-traumatic stress injury, major depression, generalized anxiety, adjustment disorder and addiction. Importantly, the list of causes was expanded to include causes other than exposure to trauma. An OSI is “any persistent psychological difficulty resulting from operational duties performed in the course of military service.”

At the turn of the millennium, mental health was not a popular topic of discussion among forces members, although subsequent research showed about half of CAF regular force members meet the criteria for a mental or alcohol disorder at some point in their lives.

Acknowledging problems with mental health went against the military ethos of strength, selflessness, self-reliance and stoicism. It’s difficult to seek help when outwardly you appear uninjured, when personal health is not a priority, when experiencing symptoms is interpreted as weakness, and seeking help considered a character flaw. And when you fear that admitting you need help could end your career.

Nothing less than a change in culture could end this stigma. Systemic changes included investment in mental-health education and more therapeutic as well as social support for personnel and their families.

“We’re creating a culture where soldiers now understand mental health and illness and have tools to self-evaluate themselves. They have training about mental health right from basic training on,” said Jetly. The Road to Mental Readiness training, which began in 2007, familiarizes personnel with the mental-health continuum, which describes behaviours associated with mental-health states ranging through “healthy,” “reacting,” “injured” and “ill.” Each state is assigned a colour on a graphic that is used in presentations, printed on cards handed out to individuals, and viewed online.

“Soldiers now talk about themselves being in the yellow range, or green, or red,” said Jetly. “They’ve got self-assessment apps, have learned coping skills, how to help each other. [They know] not to wait until you break to go to the doctor.”

In the early 2000s, Grenier fought for the establishment of a peer-support system that would tap into the age-old soldier-helping-soldier tradition. It was recognized that people with OSIs need day-to-day help and support in addition to their weekly or biweekly trips to the psychologist or psychiatrist for treatment and therapy.

A nationwide DND/VAC Operational Stress Injury Social Support network was established and now provides support groups, mentoring and one-on-one help. In 2007, family peer co-ordinators were added to provide support and advice to spouses, partners and caregivers.

“Years ago, we didn’t think about the psychological impact of the mission the way we do now,” said Jetly, who is the Chair in Military Mental Health at the Canadian Military and Veterans Mental Health Centre of Excellence. “Now we consider the potential psychological impact of missions and think about mental-health supports in theatre.”

The Canadian military has turned around its image from the 1990s, known as the Dark Decade for mental health, to gain recognition from NATO allies for its mental-health program. But it’s been slow work.

And the work is far from finished. Research in 2018 showed that not all personnel were equally exposed to mental-health education, “an important minority having had no exposure whatsoever.”

Continuing research into a variety of mental-health conditions, including PTSD and traumatic brain injury, has provided a list of evidence-based treatments and therapies, but a significant minority of patients have found no relief. Although diagnosis criteria for PTSD has existed since 1980, “not a single drug has been developed specifically for PTSD,” said Jetly.

“Now we’re looking into the biological underpinnings of these illnesses to understand what’s happening in the body,” he said. “I say body specifically because we know now these mental illnesses are whole-body diseases. We know people with PTSD have more joint pain; we’re trying to understand what’s happening with inflammation in the body, in the immune system.

“We want to match people with the right therapies, whether it’s psychotherapies or medication, without the trial and error that we seem to go through.” There is still much left to learn.

In future, it may be possible to break down PTSD into different stages or types, then give people treatment and therapy based on their specific type of disorder. “Instead of one-size-fits-all, ideally, we would have precision medicine, personalized medicine.”

It is crucial that the CAF continue enhancing its mental-health programs, Pierre Daigle, then military ombudsman, said in 2013, because “OSIs are an intrinsic component of modern military operations.”

Advertisement