Canadian nursing sisters working among ruins of Canadian General Hospital, No. 1, after it was bombed by the Germans and three nurses were killed, June 1918. [Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN No. 3404025]

They provided medical aid, comfort and peace to wounded and dying soldiers throughout decades of conflict, but it was during the First World War that the nursing sisters of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps came into their own.

Nicknamed “Bluebirds” for their blue dresses and white veils, many soldiers considered the 3,141 nursing sisters who volunteered their services between 1914 and 1918 more angel than mortal.

Some 2,500 served overseas in England, France, Belgium, Malta and in the Eastern Mediterranean at Gallipoli, Alexandria and Salonika in Greece. For countless soldiers, a nursing sister was the last face they ever saw.

In an age when a woman’s rightful place was considered to be in the home and not even at the polling booth much less at the war front, they were trailblazers whose unprecedented service and sacrifice in no small way contributed to victory in the long struggle for women’s suffrage in May 1918.

First deployed to the North-West Rebellion in 1885, their role in the Great War left indelible impressions on thousands of Canadian soldiers at home and abroad, not to mention themselves.

Mired in mud and elbow-deep in blood, they toiled in field hospitals and makeshift infirmaries located in bombed-out churches and halls over long days and nights in the face of unrelenting streams of human carnage.

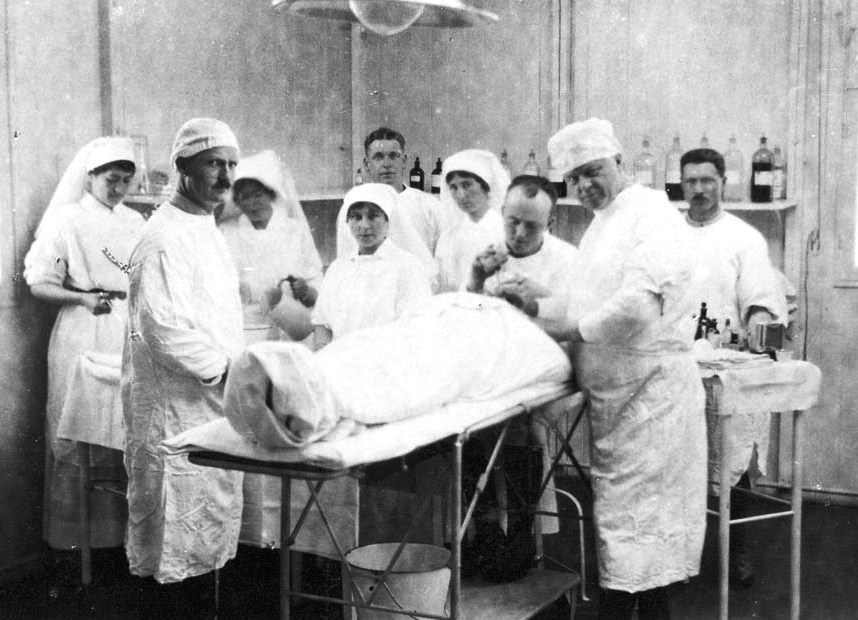

Nursing sisters assist doctors during an operation at the military hospital at Le Treport, France, 1918. [Library and Archives Canada Photo – MIKAN No. 3603393]

“There is an old soldier swathed in bandages, a cigarette alight, declaring cheerfully, ‘It’s a bit sore but it will be right soon sure.’ Further on, a round faced, dark curly-haired boy of 22 with a shattered arm, and a painful right stump (a badly shattered and gangrenous leg having been amputated) lies in restless slumber experiencing in dreams the horrors over again.

“As one passes along, a voice says, ‘It’s awful quiet here, Sister, but I seem to hear the guns yet. There were 500 of them speaking at once on Tuesday morning and it was hell.’”

About 45 nursing sisters died overseas during the First World War. They were victims of every sort—war wounds, infections, pneumonia, dysentery, meningitis and blackwater fever (a form of malaria). Many died on the home front from tuberculousis and other diseases contracted working in wartime facilities like Camp Hill Hospital in Halifax.

One hundred years ago, the spring of 1918 was a bad one for Canadian nursing sisters. In May, six died in two air-raids on Canadian hospitals.

Their single greatest loss came on June 27, 1918, when the German U-boat U-86 torpedoed the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle off the Irish coast. The lighted and marked vessel had just delivered 644 patients to Halifax. The 234 people who died that day included all 14 nursing sisters aboard, drowned when their lifeboat was sucked beneath the sinking ship.

Sgt. Arthur Knight, the sole survivor of Lifeboat No. 5, recounted how they became caught in her own ropes as the boat was lowered into the ocean. “I broke two axes trying to cut ourselves away, but was unsuccessful,” he recalled. “We tried to keep ourselves away by using the oars, and soon every one was broken.

“Finally the ropes became loose at the top and we drifted away, carried towards the stern, when suddenly the poop deck broke away and sunk.”

Matron Margaret Fraser asked him: “Sergeant, do you think there is any hope for us?” He replied no, moments before they met their fate.

“The suction drew us quickly into the vacuum,” Knight said. “There was not a cry for help or any outward evidence of fear.

“The last I saw of the nursing sisters was as they were thrown over the side of the boat. It was doubtful if any of them came to the surface again. I myself sank and came up three times, finally clinging to a piece of wreckage and being eventually picked up by the captain’s boat.”

All but two of the sisters, who were in nightgowns, died in uniform. It all happened in just 10 minutes.

Minnie Follette, a 1909 graduate of the Victoria General Hospital School of Nursing in Halifax, was among 14 Nursing Sisters who died in the June 1918 sinking of the hospital ship Llandovery Castle off the Irish coast. Follette, who had set out with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1914, is memorialized in the Anglican cemetery at Fox River, N.S.

Among the victims was Minnie Follette, a 1909 graduate of the Victoria General Hospital School of Nursing in Halifax. Follette had joined the No. 2 Canadian Army Medical Corps Hospital in 1911, enrolled in a special military nursing course in 1912 and set sail with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1914.

She served in hospitals in England and at the front in France before she was treated for nervous exhaustion in 1917. She was later assigned to the “lighter” task of staffing hospital ships, transporting wounded soldiers back home to Canada.

Lost at sea, Minnie Follette was memorialized by her brother with a rough-hewn stone monument in the Anglican cemetery at Fox River, N.S., its face engraved with floral embellishment and an etching of the ship.

A period depiction of the sinking of the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle on June 27, 1918, by U-86. The lighted and marked vessel had just delivered 644 patients to Halifax. The 234 people who died that day included all 14 nursing sisters aboard, drowned when their lifeboat was sucked beneath their sinking ship.

The German U-boat crew interrogated some of the Castle survivors in the belief the ship was carrying American flying officers and ammunition. After realizing their mistake, they tried to destroy the evidence by ramming and firing at the lifeboats. Only one lifeboat escaped with 24 eyewitnesses, including Knight.

“The sinking of the Llandovery Castle and the deaths of those aboard was considered a war crime and one of the First World War’s greatest naval atrocities,” Lesa Light, RN, wrote for Canadian Nurse in 2016. “The event became the rallying cry for Canadian troops during the offensive of the last hundred days of the war.”

The nursing sisters were memorialized on a marble sculpture erected in the Hall of Honour on Parliament Hill during the 13th general meeting of the Canadian Nurses’ Association in 1926.

The sculptor was an army veteran—George William Hill of Montreal, who specialized in public memorials. His nurses’ memorial depicts a French-Canadian religious sister nursing a sick First Nations child while a mistrustful Iroquois warrior looks on. To the left, two uniformed nursing sisters tend a wounded soldier while in the centre stands the draped figure of Humanity with outstretched arms, her left hand bearing the caduceus, the emblem of healing.

“Erected by the nurses of Canada in remembrance of their sisters who gave their lives in the Great War, 1914-18, and to perpetuate a noble tradition in the relations of the old world and the new,” it says.

“Led by the spirit of humanity across the seas, woman by her tender ministrations to those in need has given to the world the example of an heroic service embracing three centuries of Canadian history.”

More than 4,000 Nursing Sisters served during the Second World War.

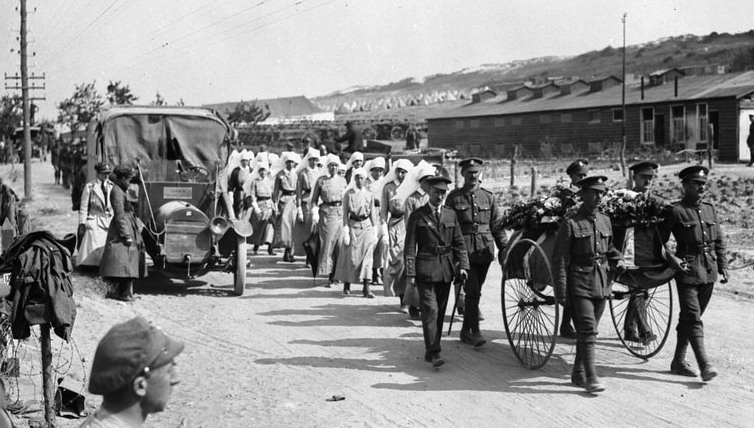

Funeral of Nursing Sister Gladys Maude Mary Wake, Canadian General Hospital No. 1, who died of wounds received in a German air raid, May 1918. [Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3624517]

Advertisement