When Carol Kozinski walked into a Canadian Armed Forces recruiting office in 1981, one of the first questions she was asked was what trade interested her.

Kozinski, who was 20 at the time and had been roughnecking aboard offshore oil rigs, said she wanted to be a mechanic.

“Oh,” she was told, “you’re too cute to be a mechanic.”

Now 55 and retired from the military, Kozinski asked that her name be changed for this article to protect her contract work. She’d spent 35 years as a service tech in the CAF, working on virtually everything it flies, from Sea Kings to CF-18 Hornets.

She’s seen a lot of changes from the days when Playboy centrefolds adorned every tool cabinet, but doesn’t believe they’re enough to significantly alter the composition of what remains an overwhelmingly male-dominated field.

Chief of The Defence Staff General Jonathan Vance has vowed to boost the proportion of women in the military by one percentage point a year until it reaches 25 per cent from the current 14.

But ask Kozinski if that goal is realistic and her reply is a blunt no.

“If you make the Forces 25 per cent women, what trades are we looking at, is really what my question would be,” she says. “And how are you going to entice the new generation with old equipment? And what missions are we doing? Because you have to give them something to go for. How are you going to get 25 per cent with nothing to give them as a carrot?”

Auditor General Michael Ferguson reported in November that success in reaching overall recruiting targets depends heavily on increasing the recruitment of women, but he noted the CAF had not implemented special employment-equity measures.

About half the women in the Canadian military are concentrated in six occupations: resource management support clerks, supply technicians, logistics officers, medical technicians, nursing officers and cooks.

“It is difficult to attract, select, train and retain more women in the Canadian Armed Forces without implementing special employment equity measures,” Ferguson reported.

Then there’s the stigma surrounding treatment of women in the Canadian military. Numerous reports have put the issue of sexual misconduct front and centre.

The most recent, a Statistics Canada report released in the fall, said bad sexual behaviour remains relatively widespread among the country’s soldiers, sailors and air force personnel despite concerted efforts to eradicate it.

The Statistics Canada survey of 43,000 members found that 960, or 1.7 per cent, reported they’d been victims of sexual assault during the previous 12 months, either in the workplace or at the hands of military members, Defence employees or contractors.

That’s almost double the incidence among workers in the general population (0.9 per cent) over the same period—and the broader sample was not limited to sex assaults in the workplace or by colleagues. The Forces survey did not include civilian staff or reservists.

The results, though they had to be expected, nevertheless angered Vance, who has made tackling the issue of sexual misconduct a priority of his tenure. “I gave an order to every member of the Canadian Armed Forces that this behaviour had to stop,” Vance said. “My orders were clear. My expectations were clear. And those who choose or chose not to follow my orders will be dealt with.”

The numbers came on the heels of a watershed report by former Supreme Court justice Marie Deschamps, who said in 2015 an underlying sexualized culture existed in the CAF that, if not addressed, could lead to more serious incidents of sexual harassment and assault.

In response, and in one of his first acts as CDS, Vance launched Operation Honour, a comprehensive strategy aimed at eliminating the problem. It commanded the “unequivocal support” of his leadership.

“Any form of harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour is a threat to the morale and operational readiness of the CAF, undermines good order and discipline, is inconsistent with the values of the profession of arms and the ethical principles of DND and CAF, and is wrong,” he said at the time.

“I will not allow harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour within our organization, and I shall hold all leaders in the CAF accountable for failures that permit its continuation.”

Kozinski, however, said that getting anything constructive done on an issue as daunting as changing a culture is difficult given the turnover at the upper echelons of the CAF.

“Officers stay in one position for three years,” she says. “How can you get anything done? You can only get one thing done. The driving force, no matter how you look at it, is that they have a three-year lifespan.

“You have to have support; you have to have the backing of the government. In three years, somebody else takes the spot.”

The numbers would suggest Op Honour has inspired somewhat lacklustre confidence across the military. While 98 per cent of regular force members told Statistics Canada they were aware of the order, only a third said they believed it will be very or extremely effective, 37 per cent said it will be moderately effective, and 30 per cent said it will only be slightly effective or not effective at all.

The military ombudsman, Gary Walbourne, called the report’s overall results “extremely troubling,” adding they “mirror the complaints received by this office over the last 18 years.”

“While I remain positive about the approaches taken.… I believe more needs to be done—the success of Op Honour depends on it,” said Walbourne.

Indeed, the Statistics Canada survey suggested many of the rank-and-file still seem to be in denial when it comes to sexual abuse, defined by the agency as unwanted sexual touching, sexual attacks and sexual acts to which the victim is unable to consent.

Only 36 per cent of men and half of women respondents said they felt inappropriate sexual behaviour is a problem in the military, despite Vance’s own insistence in August 2015.

Kozinski says she was subjected to sporadic incidents of unwanted sexual behaviour over her 35-year career—including an uninvited kiss from a pilot (“I let him know in no uncertain terms that I was not down for that and left the plane”)—but, still, she thinks the problem is overblown.

She says she personally knows of one woman who was sexually assaulted during her time in the CAF. The military, she said, is “an easy target” whose failings receive a disproportionate degree of attention.

Rear-Admiral Jennifer Bennett, who heads the military’s sexual misconduct response team, said five cases of sexual assault went to court martial between January and November 2016, with four convictions and two imprisonments.

Another 30 personnel were stripped of their commands or removed from supervisory positions for inappropriate behaviour, while nine were reprimanded, fined or punished after summary trials. One was dismissed from the military.

Eighteen months after Deschamps’ findings were submitted, a military progress report said that two of the retired justice’s 10 recommendations had been met.

The rest, it said, were being addressed.

“Operation Honour has received a focus that few other imperatives have received in modern Canadian Armed Forces history,” said the progress report, released in September. “There is much to be done in the months and years ahead.

“Changing culture will not happen overnight.”

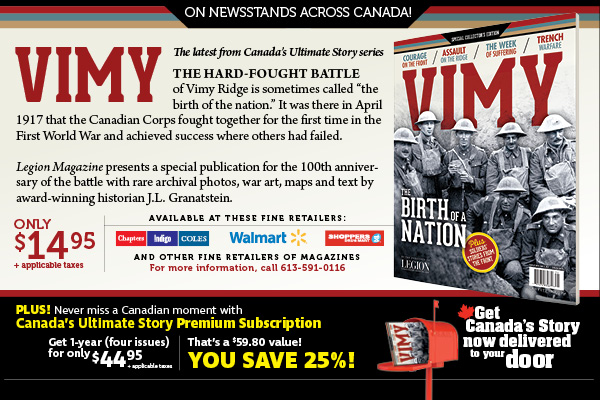

Advertisement