The theatrical release poster for They Shall Not Grow Old shows the original footage and its reworked version. [Warner Brothers/Wingnut Films]

It comes at the storyline’s transition from the war’s outbreak in 1914 and the enthusiastic queues of volunteers and recruits-in-training, rendered entirely in restored black-and-white, to the battlefront trenches of France, where the old footage emerges in full-colour, its detail and currency jarring to those who’ve only seen the time through the filters of scratched and faded monochrome.

There is a line of Tommies wending their way through a trench, at the middle of which shuffles a uniformed boy not more than 15 or 16 years old. He is staring straight into the camera lens from beneath his helmet, the kind of thousand-yard stare that comes from living in sustained, sleep-deprived terror, hunger and filth.

A collective gasp ripples through the audience attending a one-day showing of the film as the palette of brown mud, khaki combat kit and warm skin tones floods the screen and that face—that face—gazing right through each individual in the theatre, it seems, is suddenly doing so with unnerving life and presence.

Jackson drew from 100 hours of Imperial War Museums (IWM) footage along with 600 hours of archived interviews with Great War veterans to make a gripping 99-minute film, but it is this 20 seconds or so that makes the most lasting impression.

It’s as if those tired and fearful eyes are speaking directly to you, leaving you with the unanswerable question of what happened to this kid in that slaughter.

Jackson, a New Zealander who directed The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit trilogies, suggests the kid is simply fascinated by the novelty of the movie camera, that while he may have been to the cinema and seen a film or two, he had probably never seen how they’re made.

Maybe so, but there is something more in that face, that look.

You want to reach out and pull him from that hellhole.

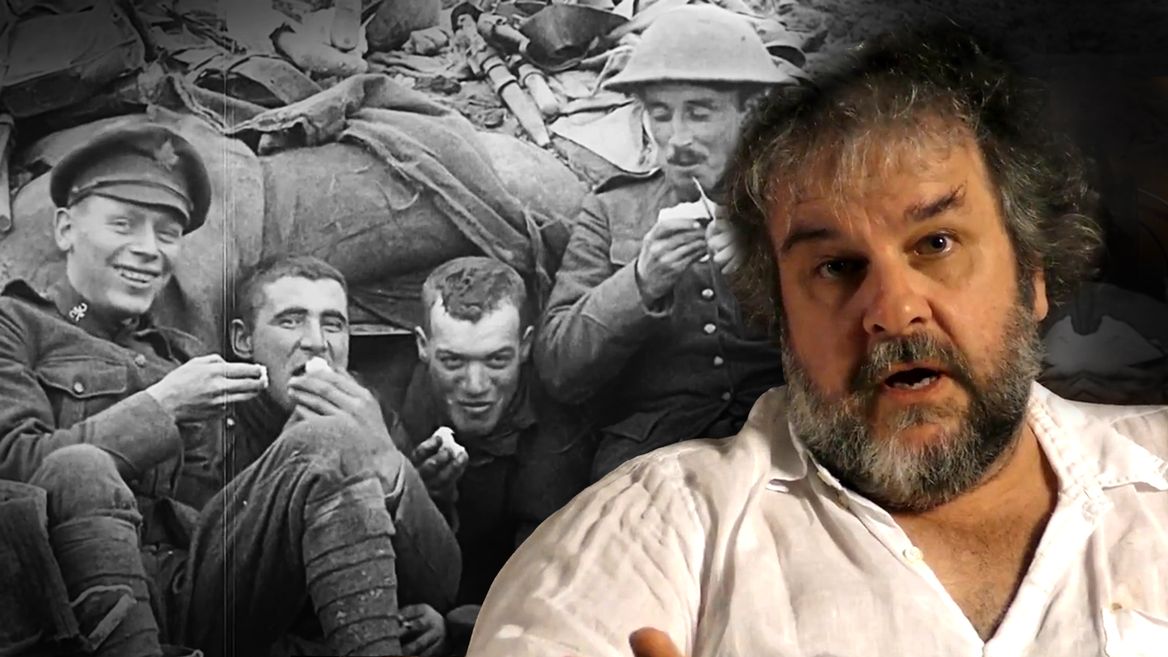

Peter Jackson, director of They Shall Not Grow Old.

“I’ve been lucky enough see 100 hours of First World War footage and, God, the faces are unbelievable,” Jackson told The Guardian newspaper. “These people come alive and you are instantly drawn to them. They become real people. People that you recognize from work. People that you’ve been to school with.”

People, you can’t help but notice, with really bad teeth.

They Shall Not Grow Old is a seminal work, bringing modern technology to bear on old film as never before. Much of it came from second- or third-generation copies of silent footage, hand-cranked at anywhere from 10 to 18 frames a second instead of today’s standard 24. This is what gave the era that comical sped-up look.

Commissioned for the Armistice centenary by the IWM and 14-18 NOW (a centenary project) in association with the BBC, Jackson narrowed his stockpile to 40 hours of footage, digitized it, restored it and slowed it to normal speed.

Only later in the process did he decide to colourize it with the best rendering 21st-century technology and talent can muster.

“I had no idea what the result would be because I had never done it before,” he said. “I had never taken an old film and thought, ‘How can we use our computers to make this look good?’

“When it came out the other end, I was absolutely amazed. It was one of the times in my life when computer technology actually stunned me. I didn’t realize how good it could be. Then I immediately thought: every single archive in the world should be restoring its film, because it can be done. We don’t have to look at sped-up and stretchy film anymore.”

Film footage of the day was also predominantly static—the tripod-bound cameras didn’t move, and they shot wide. Today’s audiences are used to seeing more variety, including tighter, moving shots. So Jackson cropped some of the film and used the excess space to introduce camera movement, panning, zooming in or out, or shifting from face to face.

He brought in forensic lip-readers to interpret what people in the footage were saying, then hired voice actors to dub in the sound, including the reading of a message to troops about to go into battle at the Somme.

They weren’t just any actors: they were specific to the soldiers pictured, their accents regionally correct so if it was a Yorkshire regiment, the actors had Yorkshire accents, and so on.

Then there are the stories and observations of the veterans themselves. There is no narration, only the voices of those who fought as they recount in vivid detail the excitement of enlistment, the rigours of training and the harsh realities of life at the front.“These boots don’t fit me,” one recruit told the supply sergeant.

“There’s no such thing in the army as boots that don’t fit,” came the reply. “It’s your feet that don’t fit the boots.”

Day-to-day life in the army was an eye-opener for many: “You heard words you never dreamed existed.”

“Although they were young in years,” explained one, “it wasn’t long before they were quite worldly men.”

They took water from steam engines and water-cooled machine guns to make their precious tea. They stole watches from German prisoners. And they made barricades from the bodies of German and Allied dead.

The consensus among the British troops was that the Bavarians were good chaps; the Prussians weren’t. A surprising number of the enemy spoke English, the veterans said. One had been a waiter at the Savoy in London.

“They had a job to do—like us.”

As the war carried on, some citizen soldiers “developed the animal character of killing,” while many became resigned to their fate: “You realized that sooner or later you were going to get the chop—you were either going to be killed or wounded.”

An officer reads a message from headquarters to British troops before the Somme. Jackson, himself a noted collector of vintage war artifacts, found the message in an archive after a forensic lip-reader deciphered what the soldier was saying. [Warner Brothers/Wingnut Films]

Parts of the film are graphic, showing dead and wounded in ways that First World War casualties have rarely been seen, with descriptions to match. One veteran talks of encountering a mate with fresh wounds so devastating (he describes them in graphic detail) that he shot him to end his misery.

Victory brought a sense of relief but no joy to the soldiers. Some felt like they had been “kicked out of a job.” The film, now back to black-and-white, describes how they returned to families and friends who had “no conception of what it was like.”

The veterans lived as “a race apart.” Unemployment was high. Signs on shops declared, “No Servicemen Need Apply.”

One veteran returned to work and a colleague asked: “Where’ve you been? On nights?”

They Shall Not Grow Old isn’t intended to be a comprehensive history of the First World War and doesn’t pretend to be anything more than it is—an account of what it was like to be in the trenches on the Western Front, delivered by those who were there, in words and pictures. They were British but they could have been Canadian, American, Australian or Kiwi.

To attempt anything more or incorporate other accounts, said Jackson, would have diluted the impact.

“There are probably five or six films of this sort that could be made from that archive,” he said. “You need to do something focused and intensely and do it justice, or you kind of spread yourself too thin. It was a decision I had to make.”

To the purists who believe he meddled too much, he says: “We’re simply taking 100-year-old footage that looks appalling…. We’re not adding anything that wasn’t there on the day it was shot. We’re simply bringing it back to what it was 100 years ago. That’s exciting, because in doing so we’re bringing these guys back to life.”

After its initial theatrical release in January, Warner Bros planned to open the film in 25 markets in February. Because it missed the Oct. 1 filing deadline, however, it was deemed ineligible for Academy Award consideration both this year and next.

Boasting a 97 per cent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, They Shall Not Grow Old had grossed almost $8.3 million in the United States and Canada by Feb. 1, totalling nearly $10 million worldwide. It is slated for a Feb. 26 release on iTunes.

___

The film’s title, They Shall Not Grow Old, is a reference to “They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old” from the 1914 poem “For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon.

Advertisement