German troops attack Dead Man Hill (Le mort homme) near Verdun in 1916. [Wikimedia]

Involving more than 30 countries in theatres spanning the globe, the “war to end all wars” was, by most accounts, a global war. No war before it exceeded its toll of some 40 million dead.

But it was not actually the first world war. That title goes to the Seven Years’ War of 1756-1763, involving some 46 belligerents in theatres spanning Europe, North America, the West Indies, South America, West Africa, India and the Philippines.

A Seven Years’ War collage depicts Lord Clive meeting with Bengali Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey in June 1757; the victory of Montcalm’s troops at Carillon in July 1758; Frederick the Great of Germany at the battle of Zorndorf in August 1758; and Austrian General Ernst Gideon von Laudon at the Battle of Kunersdorf in August 1759. [Wikimedia]

The Napoleonic Wars followed in 1803 and continued until 1815, absorbing some 37 countries, its battles touching on five oceans and at least four continents, including North America, where they helped fuel the War of 1812.

The term “First World War” wasn’t widely adopted in reference to the 1914-1918 conflict until after WW II when, writes Heather Jones of the London School of Economics, her fellow historians deemed it appropriate because it was “the world’s first industrialised ‘total’ war.”

The First World War consolidated mass-conscripted armies, rapid transportation, telegraph and wireless communications—along with total war, a concept first advocated by German general and military theorist Erich Ludendorff.

German general Erich Ludendorff is credited with the concept of total war. [Wikimedia]

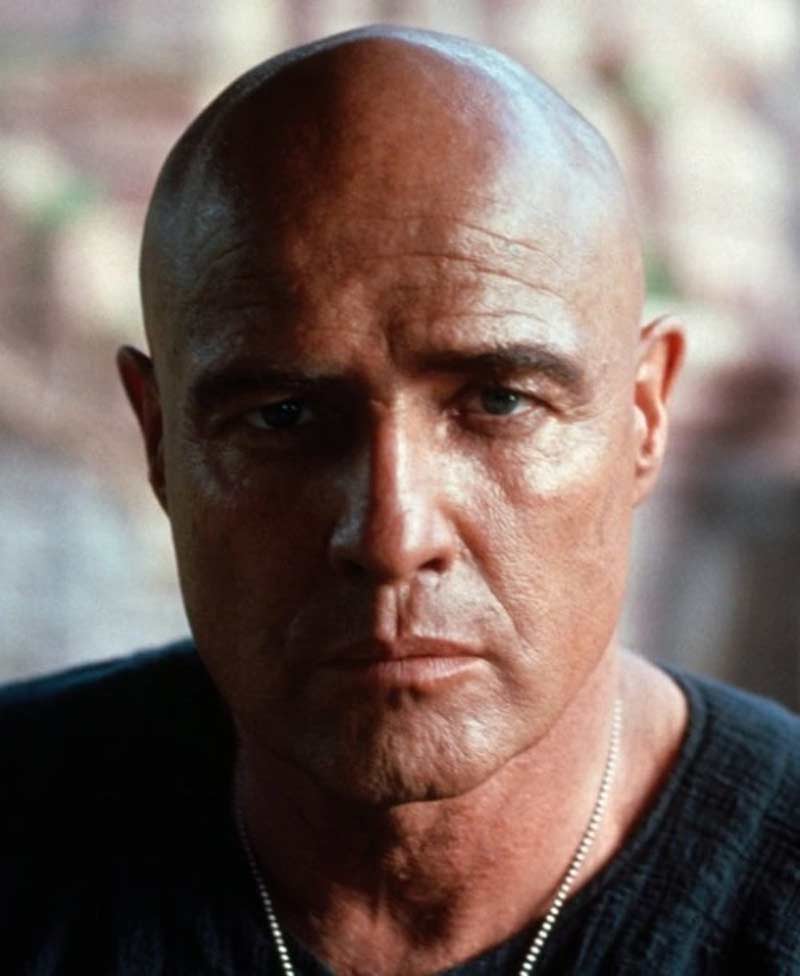

“You have to have men who are moral, and at the same time, who are able to utilize their primordial instincts to kill without feeling, without passion,” said Colonel Kurtz in the epic Vietnam War film Apocalypse Now. “Without judgment.

“Without judgment,” repeated Kurtz, played by a shaven-headed Marlon Brando. “Because it’s judgment that defeats us.”

Apocalypse Now’s mad colonel, Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando, was a strong proponent of total war.

The Great War and its WW II successor did redraw maps in far corners of the globe.

The First World War brought on the wide-scale use of rifled infantry weapons—including machine guns—capable of unprecedented accuracy and rates of fire. Cannons all but disappeared in favour of mobile, more accurate high-velocity, breech-loading artillery guns. Then there were chemical weapons; tanks and armoured vehicles; steel warships; submarines and the airplane.

“This is the Great War,” The Independent magazine wrote in August 1914. “It names itself.”

Yet Jones suggests the titles “First World War” and “World War One” are misleading. While the Seven Years’ War, the Napoleonic Wars and the Second World War were fought globally with high-stakes outcomes on numerous fronts, she notes “the key fronts that would decide the outcome of the [First World War] were all in Europe.”

The Great War and its WW II successor did redraw maps in far corners of the globe, notably Eastern Europe, Persia and the Middle East, along with the Korean peninsula—which contributed to ethnic tensions, instability and war for the rest of the 20th century into the 21st.

But it was the outcomes of the big wars of the 18th and 19th centuries and subsequent colonial ties that drew many third-party countries into the great conflicts of the 20th—including dominions of the British Empire such as Canada, Australia and South Africa.

At least 70 million people died in the Second World War, almost twice as many as in the First. This compares to the pre-industrial deaths of some six million soldiers, sailors and civilians in the Napoleonic Wars and about a million in the Seven Years’ War, both of which lasted longer than either of the acknowledged world wars. Their tallies were limited by the relatively crude weapons they employed.

Winston Churchill, who as prime minister guided Britain through WW II, described the Seven Years’ War as the “first world war.”

It restructured the European political order and affected events worldwide. It set Britain on its course toward world dominance in the 19th century—Britannia ruled the waves—spurred Germany’s rise, fostered growing tensions in British North America and stirred pre-revolutionary turmoil in France.

Fallout from the incident was far from over. It ignited the French and Indian War.

Interestingly, perhaps tellingly, all four wars did essentially begin as European conflicts.

All except, that is, for the Seven Years’ War, named so because the war in Europe began in 1756 and ended with the treaties of Paris and Hubertusburg in 1763. But the fighting actually began in North America two years earlier, started by a fourth-generation American officer by the name of George Washington.

He would go on to become the central figure of the American Revolution and the country’s first president. But in 1754, Washington’s enemy was his future ally, the French, and it was interlopers from New France into territory the British considered theirs that raised the hackles of the 22-year-old lieutenant-colonel.

Washington had been politely rebuffed the previous November when he delivered a British demand to the French commander at Fort Le Boeuf in northeastern Pennsylvania to vacate.

Now, in April 1754, the French were building Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio River near present-day Pittsburgh. Washington was dispatched to “peacefully” confront them. What ensued was something of a debacle.

The French detachment, thought to be 1,000-strong at the fort, proved to be only about 50 men encamped 11 kilometres away, so Washington advanced on May 28 with a small force of Virginians and Indigenous allies to ambush them.

Details of the ensuing clash, known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen, or the “Jumonville Affair,” are disputed. But what is known is that the French forces were killed outright with muskets and hatchets, including their commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, who carried a diplomatic message for the British to evacuate.

French forces discovered some of their troops had been scalped and they blamed Washington, who blamed his translator for miscommunicating the French intentions. Washington was congratulated by his superiors. But fallout from the incident was far from over. It ignited the French and Indian War.

Two years later, Britain’s ally Prussia attacked the small German state of Saxony, bringing Saxony’s ally Austria, and thus Austria’s ally France—and therefore France’s enemy and Prussia’s ally, Britain—into the conflict on European soil.

“It is a sequence of events eerily similar to the domino effect by which an attack in 1914 by Germany’s ally Austria on the small Balkan state of Serbia brought in Serbia’s ally Russia, which then threatened Germany, which then declared war on both Russia and Russia’s ally France,” reported The Economist.

Indeed, it is the reason why the modern world is an English-speaking one.

The 1756 war rapidly went global. Britain and France reinforced their colonial troops in North America and started attacking each other’s colonies in the West Indies, as well as trading stations in Africa and India.

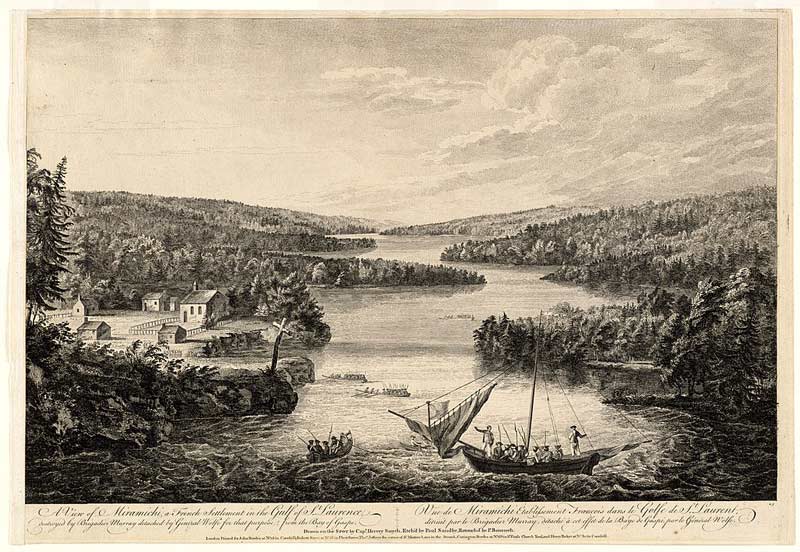

British forces raid the French settlement of Miramichi in 1758 at the site of present-day Burnt Church, N.B. [Wikimedia]

In India, some of the princely states that had recently emerged from the dying Mughal Empire joined in, and Britain ended up taking over one of them, Bengal. The war came to South America when, near its end, Spain joined the French side and attacked one of the American colonies of Britain’s ally, Portugal.

“Like the first world war, this global conflict reshaped the globe,” said The Economist. “Indeed, it is the reason why the modern world is an English-speaking one. As a colonial power, France was destroyed.

“All of North America east of the Mississippi became British, save the city of New Orleans, which became Spanish. And the foundations of British rule in India were laid as well.”

After losing his next fight at the Battle of Fort Necessity, Washington resigned his commission. He ended up leading a rebel army of North American colonists who wanted to dispense with British rule altogether. With the help of French allies, they won.

Said The Economist: “The conflict [Washington] started in 1754 was the first true world war, though it is not generally referred to as such; but you can see why some historians like to call it World War Zero.”

Forty years later, in 1803, Napoleon’s First French Empire began a series of wars with various European coalitions—seven of them, five named for the coalitions that opposed him and two for the theatres in which they fought.

Three French defeats—to Admiral Horatio Nelson’s fleet at Trafalgar in 1805, which secured British dominion over the seas, and to coalition armies at Leipzig in 1813 and Waterloo in 1815—ended Napoleon’s reign and fostered profound changes in Europe and beyond, along with a relative peace that lasted until the Crimean War in 1853.

Advertisement