Play-by-play reporting by Foster Hewitt (above) had Canadians glued to their radios during the war. [Glenbow Archives/IP-13n-1-1; ]

On April 1, 1942, Canada’s Minister of National War Services, Joseph T. Thorson, issued a statement advising his fellow citizens that the country’s human and material resources were being mobilized for total war. “Thus far Canada has been an essential and vital factor in holding the forces of liberty intact and preventing their collapse,” Thorson stated, “but more will be required of us.”

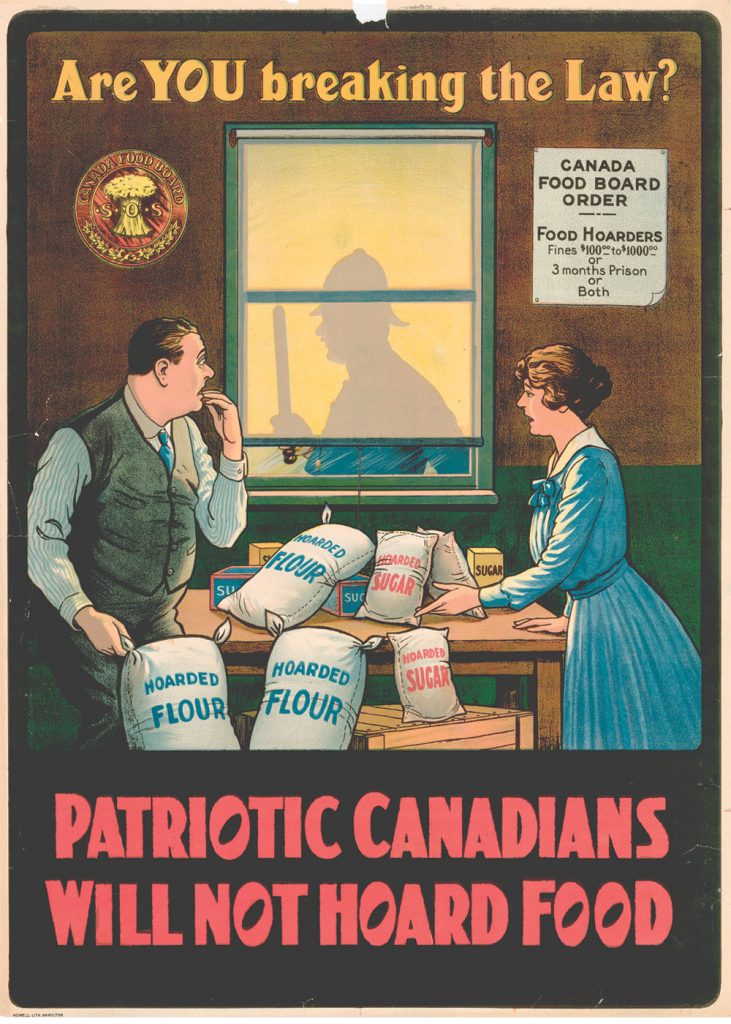

Already, some 600,000 men and women were working in munitions plants, the minister said, but another 100,000 were needed and the positions would be filled even if people had to switch jobs or relocate. A government advertisement appeared in newspapers a few days later under a headline in big, bold capital letters: “LOYAL CITIZENS DO NOT HOARD.” There was a law against hoarding and violators were liable for fines of up to $5,000 and a prison term of up to two years. “Avoid all unnecessary buying,” the ad stated. “Avoid waste. Make everything last as long as possible.”

Hockey was a welcome distraction while posters reminded Canadians that hoarding was illegal. [LAC/C-095280]

Day after day that spring, the front pages of newspapers and many inside pages were given over almost entirely to coverage of the war that had convulsed Europe, North Africa and much of southeast Asia. Bomber Command in Britain was hitting industrial plants in the Ruhr Valley—Germany’s industrial heartland. The Soviet Union, meantime, was then engaged in a life and death struggle with the German Wehrmacht.

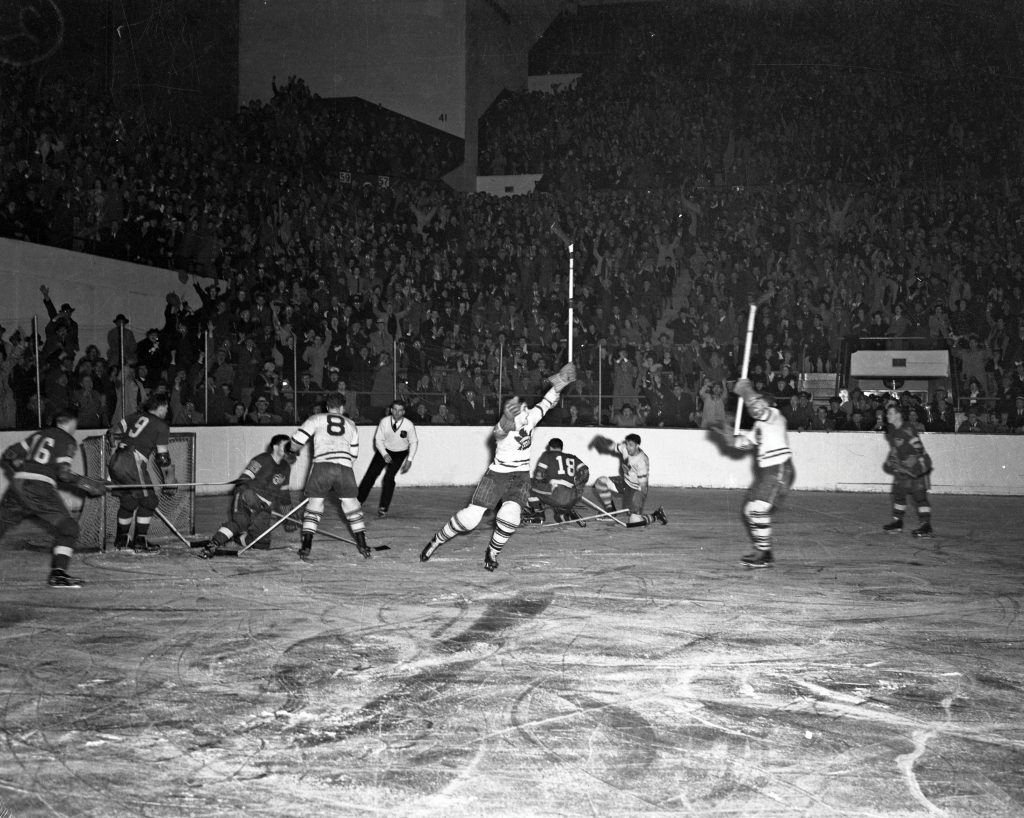

In those dark days, the Toronto Maple Leafs staged a Stanley Cup comeback for the ages and lifted the spirits of beleaguered Canadians from coast to coast. The Leafs faced the Detroit Red Wings in the final, which opened on Saturday, April 4, in Toronto. They lost that game, the next one and the next and found themselves down 3-0. No National Hockey League team had ever recovered from such a deficit and, after one of those losses, the Toronto Star reported: “There was gloom around the Leafs dressing room as thick as a Vancouver fog. The players walked softly and spoke in the hushed tones of people in the presence of a beloved dead.”

Then something nearly miraculous happened. The Leafs won games four, five and six, setting up a seventh game, sudden-death finale to the series. A record 16,218 fans jammed Maple Leaf Gardens. Hockey fans across Canada sat nervously by their radios listening to Foster Hewitt’s play-by-play and Detroit coach Jack Adams, who was suspended for attacking the referee after game four, paced back and forth in the Wings dressing room listening to the same broadcast.

The Wings took a one-goal lead into the third. The Leafs Sweeney Schriner tied it, Pete Langelle scored the winner and Schriner added an insurance goal with less than four minutes to go. “Shortly after 10:20 on Saturday night, before the greatest throng that ever looked at a hockey game in the Dominion of Canada, Leaf coach Hap Day was flying over the ice,” the Star reported. “He caught Schriner with one arm over his shoulder. Hap brought his other fist playfully to Sweeney’s cheek and playfully punched it.

“Hello champ,” he said.

“Champ yourself,” Schriner replied and he and Day joined the rest of the Leafs at centre ice and NHL president Frank Calder presented the Stanley Cup. The big Gardens crowd cheered deliriously and Canadians who were listening on the radio shared

their joy.

By the time the war began, Hewitt’s Saturday night broadcasts from Maple Leaf Gardens had become part of the fabric of Canadian life—in English Canada at any rate—and the Leafs had become a beloved national institution. Hewitt’s weekly broadcasts provided Canadians with welcome relief from all the hardship and anxiety brought on by the war.

The Toronto Maple Leafs celebrate another goal against Detroit in the 1942 Stanley Cup final. [Hockey Hall of Fame/000003346]

Bill Fitsell, a retired Kingston Whig-Standard reporter and founding president of the Society for International Hockey Research, was an avid young Leaf fan at the time and eagerly awaited those Saturday night broadcasts. After finishing high school in his hometown of Lindsay, Ont., he went straight from the classroom to a job at a local munitions plant, which employed 1,200 of the community’s 7,000 residents.

Fitsell had a pre-game ritual he followed on Saturday nights. He collected the five-by seven-inch Bee Hive corn syrup photos of NHL players, which were issued at the start of each season, and he used them as a visual aid while listening to Leaf broadcasts. “The league was so small in those days, you got to know every player intimately,” he says. “I would clear off the dining room table and lay out the Bee Hive photos as Foster announced the lineups. That was my television.”

But in the wake of the Leafs miraculous Stanley Cup comeback, which had brought so much joy to so many hockey fans, the men who ran the NHL were seriously considering suspending operations for the duration of the war. Some teams were losing money, the league was operating one of its seven franchises—the perennial money-losing New York Americans—and most clubs were having trouble finding enough capable players to fill their rosters.

In early May 1942, New York Rangers general manager Lester Patrick phoned his coach Frank Boucher at his farm near Kingston, Ont., and told him: “It looks very bleak. I would advise you to look for something else.”

The situation only got worse over the summer. Some 74 NHLers had either enlisted voluntarily or been ordered to report for duty and the entire NHL comprised only about 120 players at the time.

The Boston Bruins had lost their formidable Kraut Line of Milt Schmidt, Woody Dumart and Bobby Bauer, so called because they were all from Kitchener, Ont., a city with a large German-Canadian community. The high scoring linemates left in February 1942 to join the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Three of the Leafs four starting defenceman—Rudy (Bingo) Kampman, Wally Stanowski and Bob Goldham—enlisted over the summer. The Canadiens lost goaltender Paul Bibeault and defenceman Ken Reardon. And dozens of lesser known players also departed.

Furthermore, some observers questioned whether able-bodied young men should be playing professional sports when thousands of their peers were serving their country and, in many cases, sacrificing their lives for the cause of freedom. But federal authorities in Canada and the United States thought otherwise. Both governments issued statements on the same day in mid-September ordering the major professional sports league to continue operating.

Elliott M. Little, director of Canada’s National Selective Service, the agency that drafted men for military service, issued a one-paragraph statement which read: “The number of men involved is so small that it is not considered desirable to destroy the existing media of relaxation through which hundreds of thousands of people—many of them war workers—find enjoyment, which permits them to contribute their maximum to production while they are on the job.”

At that, NHL President Calder summoned owners and managers to a meeting to plan the 1942-43 season. The owners decided they could no longer keep the Americans afloat. They folded the franchise and the six-team NHL—later to be branded and marketed as the Original Six—was born. They also extended the season to 50 games from 48.

Players continued to enlist, but some teams suffered more than others. The Rangers fell from first in 1941-42 to last in 1942-43. They lost goaltender Jim Henry, their two best defencemen, Art Coulter and Muzz Patrick, and their top forward line of Alex Shibicky and Mac and Neil Colville.

None of that mattered much to ardent fans like Bill Fitsell. He joined Royal Canadian Navy in September 1942 and after several months of basic training, first in Toronto and then in Victoria, he was sent to Halifax and initially sailed on the HMCS Outremont. “Sometimes we would get Foster Hewitt when we were out in the eastern Atlantic on anti-submarine patrols,” he recalls. “When we could get a Canadian broadcast we felt we were at home. It was quite a thrill.”

The Leafs gave their fans plenty to cheer about for duration of the war and so did the Montreal Canadiens. The Canadiens had won the Stanley Cup in 1930 and again in 1931 but the rest of the 1930s proved to be a dreadful decade for French Canada’s beloved Habs. There was talk of folding the team in the late 1930s and the Canadiens posted their worst record ever—10 wins, 33 losses and five ties—in 1939-40.

Goalie Bill Durnan and Maurice Richard chat at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. [Hockey Hall of Fame/000007586]

The Canadiens hired Dick Irvin as coach in the summer of 1940 and built a contender over the next few seasons with addition of goaltender Bill Durnan, defenceman Butch Bouchard centreman Elmer Lach and, of course, Maurice (Rocket) Richard. “I remember Ray Getliffe telling me that the first couple of years he played in Montreal all he could see were the empty brown seats in the Forum,” says Dick Irvin Jr. “In 1943-44, the Canadiens didn’t lose a home game until the opening night of the playoffs. The Forum held 9,000 and the team was selling out. The fact that the team got better each year made a difference to the people. No question about it.”

In the spring of 1944, the Canadiens beat the Leafs, their fiercest rival, in five games and the Black Hawks in five to capture their first Stanley Cup in 13 years. This being wartime—a few short weeks before D-Day—ownership honoured the players with a small, private banquet at the Queen’s Hotel. Then most of the players went to work in wartime industries. Richard and three others had jobs in a munitions plant, captain Toe Blake worked in a shipyard, Lach and Getliffe in an airplane factory.

However, Rocket Richard had emerged as a bona fide NHL star and French-Canadian hero that season and one of his former coaches organized a tribute a few weeks after the season ended. Some 1,200 people attended and many came bearing gifts. Among other things, Richard received a walnut coffee table, a cigarette lighter, a wallet and a four-by five-foot framed photo of himself in action.

It was a fitting tribute and a reminder of how much hockey meant to a populace enduring all the hardship and duress of a world war.

Advertisement