In “Sixth Company Battalion,” photographer Anique Jordan cast her mother and two aunts in the uniforms of War of 1812 British forces, for which Black Loyalists from Trinidad fought. The photograph is among 70 works by 52 women artists on exhibit at the Canadian War Museum until Jan. 5.

[Anique Jordan/CWM]

Now she’s part of a sweeping exhibition featuring more than two centuries of Canadian women’s war art, her fabric-based interpretations of the tools her predecessors used, along with weapons and accoutrements of war, displayed alongside works by the likes of Mary Riter Hamilton, Molly Lamb Bobak and Gertrude Kearns.

“It’s been a really amazing experience,” Findlay said in an interview at a preview of the exhibition Outside the Lines: Women Artists and War, showing in the museum’s Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae Gallery until Jan. 5.

“Being able to see the collections and explore the archive and get to see the other artists’ work, it really sparked a much bigger interest for me.”

In “Reiko, Alberta (1945),” artist Lillian Yano Blakey depicts her mother peering out from behind the barbed wire of a Japanese internment camp.

[Lillian Yano Blakey/CWM]

She nevertheless hesitated in applying for the post, not really understanding the depth of her connection to the subject—until the medals began speaking to her.

“I kept walking past those medals and it was like he was standing there telling me: ‘Put that application in! What are you talking about? We have lots of family history in war and conflict.’”

The appointment came with funding for 12 weeks’ work with daunting direction to create an art piece that will “amplify the voices of women artists who have typically been under-represented in war art…reflect upon exhibition themes, as well as the Museum’s world-renowned war art and military collections.”

Findlay plunged into her grandfather’s own archive, reading letters, poring over old photographs and discovering more about him than she ever thought she would know.

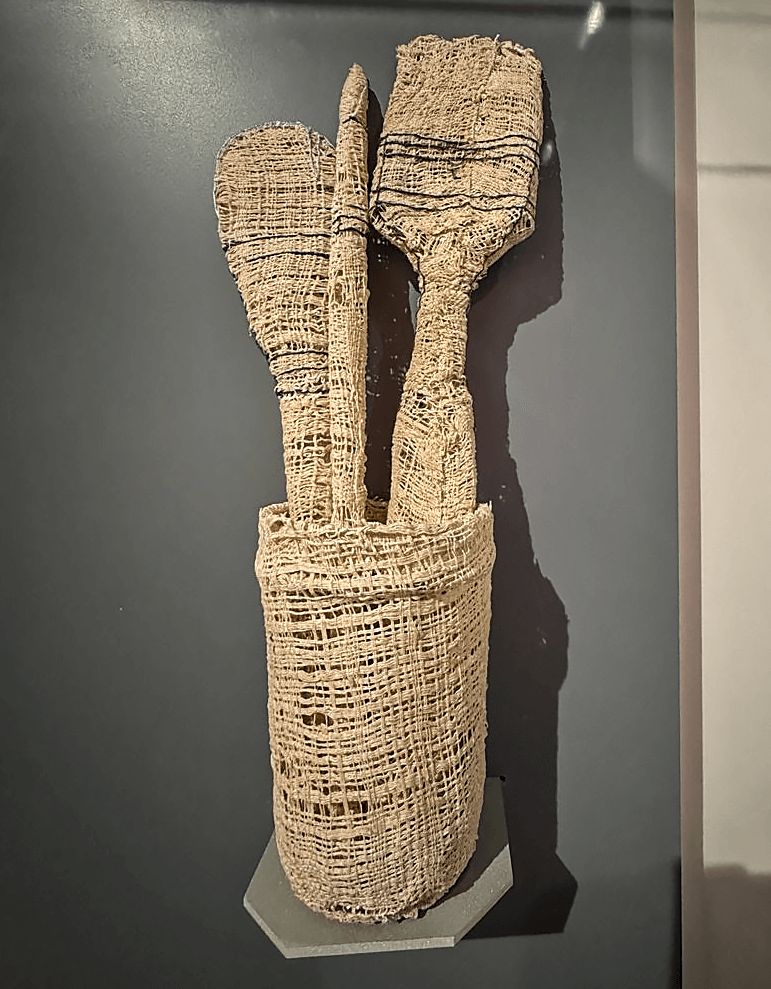

Elise Findlay’s deconstructed canvas depiction of the brushes Gertrude Kearns used to paint Major-General Jennie Carignan.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Elise Findlay/CWM]

Findlay works in various media, her choices dictated by the projects she undertakes. She selected deconstructed fabric, almost threadbare, for her museum pieces because of its tactile nature.

“It’s something we wear; it’s close to the body; it’s something that you can imagine touching and feeling that connection,” she told Legion Magazine. “So, all the objects are either pulled from other artworks from throughout the exhibition…or, I contacted some of the contemporary artists who are here now and recreated the tools they used to create the work.”

There is a wool gas mask inspired by Bobak’s Gas Drill and a painting canvas fashioned into brushes of the type Kearns used to create a portrait of Major-General Jennie Carignan.

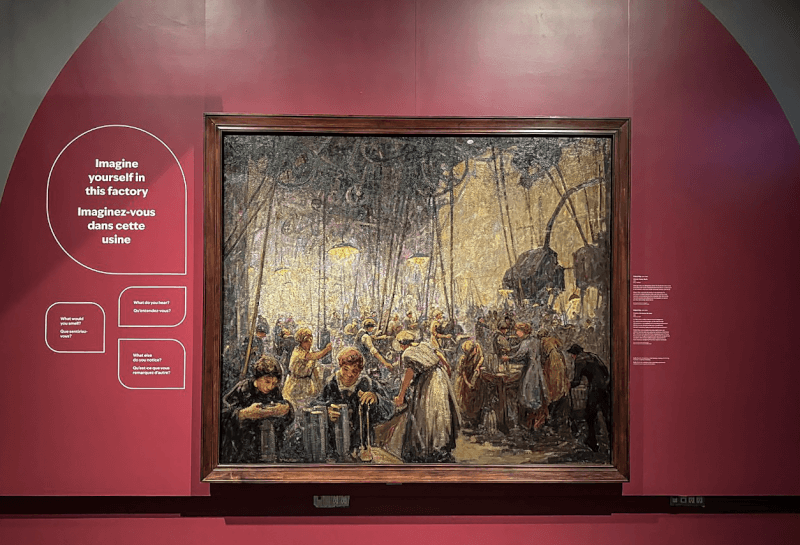

There are artillery shells made from the silk organdy that was used in WW I nurses’ veils, inspired by Mabel May’s atmospheric painting Women Making Shells, and a painted canvas camera depicting the type used by Anique Jordan to photograph her mother and two aunts dressed in the uniforms of Black Loyalists from Trinidad who fought with the British in the War of 1812.

Major-General Jennie Carignan by Gertrude Kearns.

[Gertrude Kearns/CWM]

- Beothuk Shanawdithit’s rare depictions of European violence against Indigenous Peoples in Newfoundland in 1811 and 1819;

- the trailblazer Riter Hamilton’s depiction of gun emplacements at Vimy Ridge, one of a battlefield series painted after she was refused official war artist status and got funding from veterans;

- Rosalie Favell’s photographic portraits of Canadian Rangers in the landscapes of the High Arctic;

- Lillian Yano Blakey’s depiction of her Japanese Canadian mother as a young woman peering out from behind the barbed wire of an Alberta internment camp in 1945;

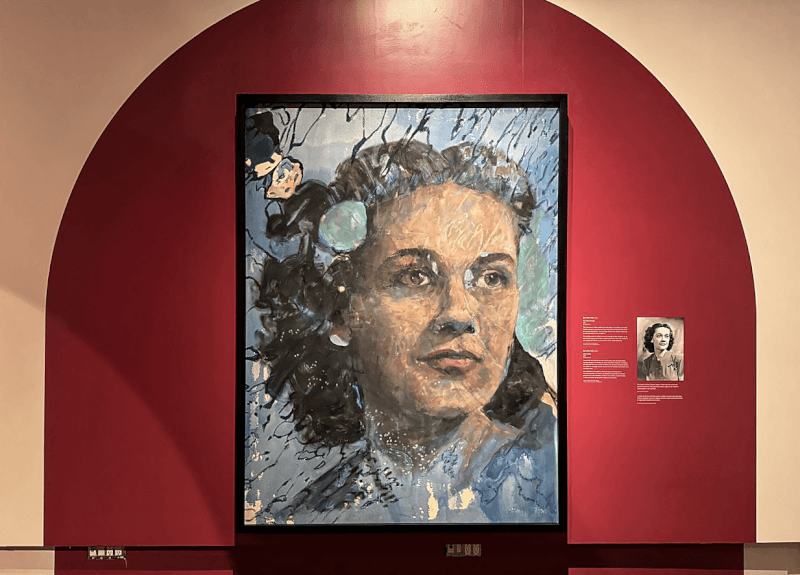

- and Beverly Tosh’s magnificent larger-than-life portrait of her mother Dorothy as a young woman, a war bride who returned to her native Canada after her marriage to a New Zealander failed.

Beverly Tosh’s portrait of her mother Dorothy as a young woman, a war bride who returned to her native Canada after her marriage to a New Zealander failed.

[Beverly Tosh/CWM]

Historian and exhibition curator Stacey Barker spent four years researching and assembling the art, the bulk of it drawn from nearly 13,000 paintings, drawings, posters and sculptures in the museum’s Beaverbrook Collection of War Art dating to 1760.

Barker says there is no “woman’s perspective” on war.

“Every artist has their own perspective,” she said. “There are 52 artists in this show and there are 52 different perspectives on war.

“But women do have a different lived experience and I think that goes into their artwork in a way that is different from the male lived experience.”

Mabel May’s atmospheric painting “Women Making Shells” (1919) conveys the bustle and stifling air of a WW I munitions factory.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Mabel May/CWM]

“I think the thing that struck me most is just how diverse the work is,” said Barker. “There are all sorts of different artworks in the show that reflect on different aspects of war that you don’t really think of when you think of war.

“There are all sorts of impacts in society from war and a lot of these works touch upon that. And it’s intergenerational, it comes down through different generations. You can have a look in the contemporary section and you can see that in a lot of these works.”

There are tentative plans to travel the exhibition after it concludes its run at the Ottawa-based museum in January 2025.

“Seed” by Dominique Blain fused two Brody helmets together, posed the question: What seeds are planted by conflict?

[Stephen J. Thorne/Dominique Blain/CWM]

Advertisement