Men gargle with salt and water after a day of working in the war garden at Camp Dix in New Jersey. The treatment was required because the influenza was spreading to army camps across North America. [U.S. National Archives]

As the First World War drew to a close, the world was hit

by the greatest pandemic since the bubonic plague

His aircraft holed and ablaze, Lieutenant Alan Arnett McLeod, just 18 years old, earned his Victoria Cross with bravery and blood in a spectacular aerial dogfight on March 27, 1918, over Albert, France.

He stood with one foot on the rudder and one outside on a wing, steeply side-slipping to keep flames at bay, while eight enemy planes peppered his Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8 from all directions. Although wounded, McLeod and his observer Lieut. A.W. Hammond brought down three enemy aircraft before crashing in no man’s land.

McLeod sustained another wound helping Hammond to safety under heavy enemy fire. McLeod spent six months in hospital in Europe, then was sent home to Stonewall, Man., in September to finish recovering from his five wounds. Five days before the Armistice, he died. But not from wounds.

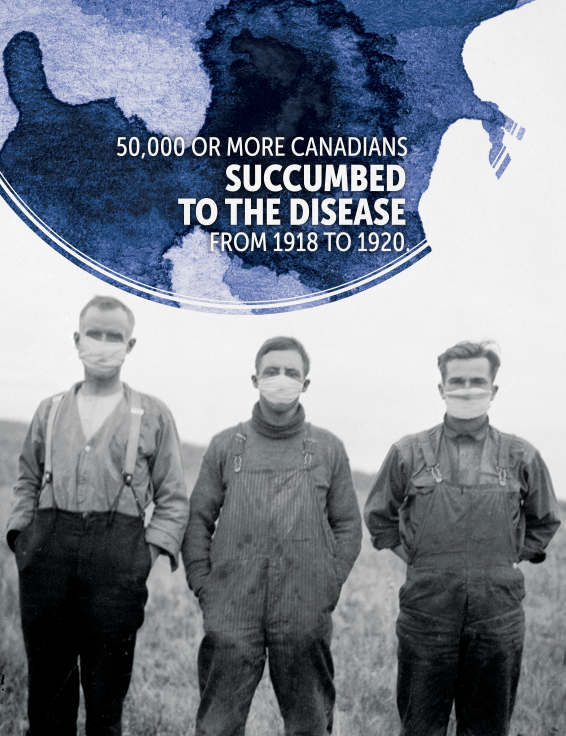

McLeod was one of thousands of soldiers, sailors and airmen who survived the war only to die of Spanish influenza, among the 50,000 or more Canadians who succumbed to the disease from 1918 to 1920.

The bubonic plague of the mid-1300s claimed up to 200 million people worldwide, but it took seven years to do so. In contrast, the Spanish flu swept around the world in less than three years, in three waves. Some 500 million people—a third of the world’s population—were infected and at least 50 million people, and perhaps as many as 100 million, died.

If the Spanish flu had arisen a decade earlier or a decade later, it might have spread slowly enough to peter out before it became a pandemic. But right then, millions of men were on the move, heading to and from battlefields.

The military provided an ideal incubator. Most soldiers were in the age group—20s through 40s—particularly vulnerable to this flu strain, and they lived in conditions conducive to its spread. Stressed, dirty, hungry, wet and cold, massed in camps, huddled in trenches and tents or jammed into troop trains and ships, warriors were easy prey.

In ships and rail cars, sick soldiers and sailors carried the infection with them to communities they passed through on the way to and from the front, and eventually, to their own hometowns and families.

“It struck all the armies and might have claimed toward 100,000 fatalities among soldiers overall during the conflict, while rendering millions ineffective,” according to Dutch military historians Peter C. Wever and Leo van Bergen.

The military was hit harder than civilians, and the United States military possibly hardest of all. More than a million men—26 per cent of the U.S. Army—were struck. About 30,000 died in training camps, never leaving North American soil. Infection and death rates were double that of same-aged American civilians.

Nearly 46,000 members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force overseas got sick and 776 died, Sir Andrew MacPhail reported in his 1925 history of the Canadian Army Medical Service. During the last four months of the war, 11,496 soldiers in Canada were stricken—up to 42 per cent of personnel in some military districts, and 19 per cent of overall forces in Canada. More than 400 died.

These figures may not reflect the true numbers, however, as not all cases were reported, particularly at the beginning of the epidemic when influenza was not a reportable disease for quarantine purposes. As well, deaths from influenza were often put down to other causes—chiefly pneumonia.

As the epidemic peaked in October 1918, German General Erich von Ludendorff’s medical staff worried about troops’ weakness should the Allies attack. “Influenza was rampant,” he wrote in Ludendorff’s Own Story. And even after it subsided, “it often left a greater weakness in its wake than the doctors realized.” He also noted a decline in the fighting power of Allied troops: “The Americans are suffering severely from influenza,” he wrote. More than 14,000 German troops died from influenza.

Men wear surgical masks to protect themselves against the Spanish flu in Alberta in 1918. [LAC/PA-025025]

Or was it in China in 1917, where a respiratory infection was killing dozens a day, just when 140,000 workers were being recruited for the Chinese Labour Corps? They would provide manpower for unloading cargo, digging trenches and graves, building railways and bridges at the front in Europe.

About 84,000 of them were secretly shipped across Canada by March 1918 in sealed rail cars, and some of the transported workers and their army guards became ill.

Or was it in the U.S.? An unusual epidemic was reported in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, near Camp Funston. On March 4, flu hit the first soldier. Within three weeks, more than 1,000 soldiers were hospitalized. Since the flu was contagious for some days before symptoms appeared, it spread along rail lines from camp to camp, then on to troopships to Europe.

The first, and mildest, wave of the disease passed through Canada in spring and early summer 1918 without stirring panic. News was widely censored in warring countries, so the population was largely unaware of the spreading threat. However, the illness of King Alfonso was front-page news in neutral Spain in late May. Thus, it became known as the Spanish flu, even though it did not originate there.

During the summertime lull in Canada, the virus mutated into a more virulent form in Europe and spread in the fall to North America and Africa via ships from England.

The first severe cases appeared in Boston at the end of August. A doctor at nearby Camp Devens wrote that the camp had about 55,000 men “or did have, before this epidemic broke loose.” Victims “very rapidly develop the most vicious type of pneumonia. Two hours after admission, they have mahogany spots over the cheek bones” and a few hours later, their faces turn blue. “It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible.”

It was horrible on both sides of the Atlantic. “Such sick, sick men. Many of them will die,” wrote nursing sister Clare Gass, who was transferred to help with an “awful plague of Spanish influenza” at Kinmel Park Military Hospital in Wales.

“The boys were coming in with colds and a headache and they were dead within two or three days,” wrote Sister Catherine Macfie at casualty clearing station No. 11 in France. “Great big handsome fellows, healthy men, just came in and died. There was no rejoicing in Lille the night of the Armistice.”

A thorough investigation of the epidemic, based on work at Bramshott Canadian Military Hospital in England, found that no specific treatment or serum worked and “the remedial measures common in civil life were hard to apply,” wrote MacPhail. Nearly all 3,836 aboard three troopships that departed Canada from Sept. 26 to Oct. 6 were ill when they arrived in Europe, and there had been 99 deaths at sea.

A burial party shovels earth on coffins of those who died from the flu in North River on the east coast of Labrador in 1918. [Wikimedia]

With the discovery of life-saving penicillin still decades away, most who died succumbed from secondary bacterial infections. But the flu itself carried off many, and to the mystification of doctors, the young and hardy, ordinarily less likely to succumb to influenza. It is thought the fall flu strain prompted an immune system overreaction, and the more robust the immune system, the worse the reaction. The virus damaged lungs, so fluid built up, preventing oxygen from getting into the bloodstream. Breathing became more and more laboured. Blood from damaged respiratory cells seeped and foamed from the nose and mouth. The inflammation spread to other organs, causing swelling and leaking of blood from damaged vessels, leading to organ failure.

This virulent flu strain spread north to Canada by road, ship and rail. The first civilian deaths were recorded on Sept. 16, following a Eucharistic Congress in Victoriaville, Que., which had many American delegates. On Sept. 18, Polish recruits from Boston, where the epidemic raged, began dying in a military training camp at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., reported Kandace L. Bogaert in Casualties of War? An ethnographic epidemiology of the 1918 influenza pandemic among soldiers in Canada.

On Sept. 20, soldiers in Quebec became sick, and although they were immediately quarantined, Captain Robertson of the Jeffery Hale Hospital in Quebec City reported that “with marvellous rapidity, it developed among the soldiers and the civilian population.” The scenario was repeated two days later, when more than 600 sick men on a U.S. troopship were hospitalized in Sydney, N.S.

From the East Coast, it spread westward, not with “injured soldiers returning home from the muddy battlefields of Europe, but with new recruits bound for a new front in Asia,” wrote historian Mark Osborne Humphries in The Last Plague: Spanish Influenza and the Politics of Public Health in Canada. Sailings of troop and hospital ships from Europe to Canada were suspended over the summer due to the threat of submarines and a lack of escort vessels.

American soldiers march through the streets of Seattle, Wash., wearing masks provided by the American Red Cross. [U.S. National Archives]

Since the flu is contagious before symptoms appear, some men aboard the train were already ill. The first sick men were offloaded for hospitals in Montreal, where new recruits and military medical personnel who had been treating flu victims came aboard. In Winnipeg, more sick soldiers were quarantined and transferred to a local military hospital. Healthy troops boarded in Regina on Sept. 29, but when the train reached Calgary, a dozen sick soldiers were sent to hospital. The SEF—and the flu—arrived in Vancouver on Oct. 2.

By October, the disease was spreading across the country as if carried by the wind. It struck swiftly and it struck hard. About 1,000 Canadians a day were dying. It ravaged communities, killed entire families. Some people died within hours of the first symptoms. Children in isolated farms and remote communities died because no adult survived to care for them. The outbreak seemed to be everywhere all at once, and it moved so rapidly that local health officials had no time to prepare. There was no co-ordinated national approach.

In pre-antibiotic times, quarantine limited spread of the disease. Provinces and municipalities ordered isolation of the sick, closure of schools, businesses and churches, and banned large public gatherings. Even the sixth game of the 1919 Stanley Cup playoff final series was cancelled. In Alberta, residents and visitors were prohibited from entering or leaving quarantined towns. Large public gatherings were banned in many cities, and people were ordered to wear face masks in public.

But those public health measures were undermined by lack of enforcement, particularly for the military.

Public health played second fiddle to the war effort. Recruitment and enlistment continued, as did troop transport, continually re-introducing the virus to camps and hospitals. Convalescing troops were sent on day trips, entertainment brought in to boost morale, visitors allowed in to quarantined barracks and hospitals. The military successfully argued that provincial governments did not have the authority to suspend transportation of conscripts. In Montreal, an honour guard was provided for a funeral, although the men had been exposed to infected barracks.

But individual military personnel recognized their role in spreading the disease. When Siberia-bound troops were transported across Canada from Toronto in mid-October, 75 were sent to hospital. “That was in the middle of that awful influenza epidemic, which we brought with us from the East,” said Captain Eric Elkington, a doctor.

Some soldiers blamed themselves. “I got the Spanish influenza,” recruit Jesse Brinson of Western Arm, N.L., said in a Heroes Remember video, one of a series produced by Veterans Affairs Canada. “I wrote a letter, had no better sense…[and sent] the disease right in the family to take the whole lot of them out the one day, never give it a thought. I wrote father and told him I was in a military hospital…[where] there was…a soldier buried every day for eight days.”

The public soon noted the connection between spread of the flu and troop movements, and chafed against wartime censorship that prevented full reporting of the epidemic. Despite this criticism, conscription and the hunt for draft dodgers continued in the fall.

“Public indignation reached a high point when it appeared that the health of individual soldiers and the civilian population was being sacrificed without any apparent military necessity,” wrotes Humphries.

Frank Oliver of the Edmonton Bulletin blamed “criminal negligence of the military authorities” for spreading the disease. “Every facility for the spread of the infection is present, and as well every cause by which its virulence can be increased. No wonder the military authorities refuse to allow information to be given out as to the number of deaths which have taken place.

“The military authorities seem to take the view that the way to deal with a virulent epidemic is to ignore its existence, and if they can keep the facts from getting into the papers, all is well. The deaths of a few common soldiers—draftees—is neither here nor there.”

Calgary newspaperman William Irvine blamed the federal government: “Where was the Order-in-Council prohibiting all travel until such time as the plague subsided?”

The realization dawned that the country needed national co-ordination of policies and procedures, leading to the establishment of the federal Department of Health in 1919.

The flu virus was identified in the 1930s and development of vaccines followed. But still some 12,200 Canadians are hospitalized and 3,500 succumb to the flu every year. And health authorities warn that we are overdue for another pandemic.

As part of the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan, flu vaccine is stockpiled by federal, provincial and territorial governments, as is anti-viral medication for lessening the flu’s effect. Each province and territory have pandemic response plans, which include how mass vaccinations can be handled and how to keep health services going if doctors and nurses are in short supply.

The Canadian Armed Forces would pitch in, just as it has done in other domestic emergencies. In case of a pandemic, it would support health authorities as needed, such as in delivering stockpiled vaccine when the country’s transportation system breaks down, or setting up temporary morgues when the system for handling the dead is overwhelmed, or a myriad of other duties.

Rather than spreading disease, as their predecessors did a century ago, the Canadian Armed Forces would be helping to fight it.

Advertisement