Studies have proven the Viking myth is just that—myth. They never wore helmets with horns and an extensive genome study has now shown they were more diverse than many thought. [iStock]

While the ships, axes and shields are a sure thing, and the beards are a pretty good bet—at least for the men—a new study has found that the adventurers and plunderers who settled in Newfoundland some 500 years before Columbus crossed the ocean were more genetically diverse than the myths would suggest.

In the largest genetic analysis of Viking remains ever conducted, paleogeneticist Ricardo Rodrı́guez-Varelal and his colleagues at Stockholm University and the Stockholm-based Centre for Paleogenetics analyzed Scandinavian burials going back 2,000 years.

The researchers compared 297 of those genomes to those of 16,638 modern-day Scandinavians and more than 9,000 people with ancestries spanning Europe and western Asia.

While genetic diversity among Vikings would have been expected given their wanderings and the results of previous studies, the findings published on Jan. 5, 2023, in the journal Cell were nevertheless striking: Viking Age Scandinavia was far more genetically diverse than its present-day populace.

“Modern Scandinavians have less non-local ancestry than Viking Age samples,” said the study. “In some regions, a drop in current levels of external ancestry suggests that ancient immigrants contributed proportionately less to the modern Scandinavian gene pool than indicated by the ancestry of genomes from the Viking and Medieval periods.”

A previous DNA study suggested that for some, at least, “Viking” was a job description, not a matter of heredity.

“Viking” is the name given seafaring Scandinavians (from present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden) who raided, pirated, traded and settled throughout parts of Europe and beyond from the late-eighth to the late-11th centuries.

Viking ships sailed as far as the Mediterranean, North Africa, Volga Bulgaria, the Middle East and Newfoundland where, centuries before Columbus reached the Bahamas, they were the first Europeans in North America.

Viking expeditions (blue line): depicting the immense breadth of their voyages through most of Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Northern Africa, Asia Minor, the Arctic and North America.[Wikipedia]

A previous DNA study suggested that for some, at least, “Viking” was a job description, not a matter of heredity.

It detailed Viking-style graves excavated on Britain’s Orkney Islands that contained remains with no Scandinavian DNA, and people buried in Scandinavia who had Irish and Scottish parents. Several individuals in Norway were buried as Vikings, but their genes identified them as Sami, an Indigenous group genetically closer to East Asians and Siberians than to Europeans.

While Vikings were typically viewed as raiders and barbarians through much of the 19th and 20th centuries, they were accomplished mariners who had their own laws, art and architecture. As depicted in recently popular television dramas, most were also farmers, fishermen, craftsmen and traders.

Those who came to Scandinavia during the heyday of Viking raiding and trading—whether merchants, missionaries or captives—have all but vanished from the gene pool.

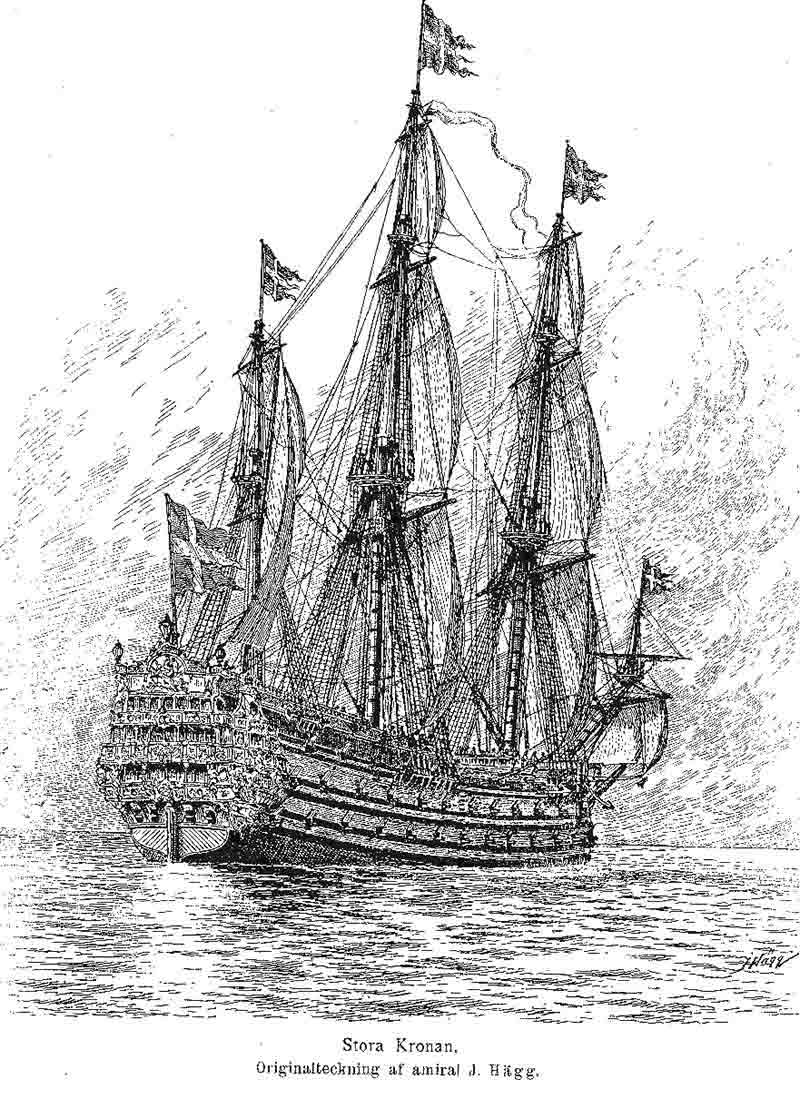

The recent study gathered DNA from a variety of sources, some newly discovered, including boat burials, chamber burials and 12 post-medieval individuals who died when the Swedish warship Kronan sank in 1676.

Swedish ship of the line Stora Kronan 1668.[Wikipedia]

British-Irish ancestry was widespread in Scandinavia from the Viking period, while eastern Baltic ancestry was more localized to Gotland and central Sweden, they explained. Traces of British and Irish ancestry are still evident in modern Scandinavian genomes.

“This is perhaps not surprising, given the extent of Norse activities in the British Isles starting in the eighth century…and culminating in the 11th century North Sea Empire,” the paper noted.

But those who came to Scandinavia during the heyday of Viking raiding and trading—whether merchants, missionaries or captives—have all but vanished from the gene pool of present-day Scandinavia.

“The drop in current levels of external ancestry suggests that the Viking period migrants got less children, or somehow contributed proportionally less to the gene pool than the people who were already in Scandinavia,” Stockholm University geneticist Anders Götherström, a report co-author, told the science journal Inverse.

Wrote Inverse’s Kiona Smith: “If you take nothing else from this study, take this: genomes usually reveal only the biggest, broadest strokes of human interactions. Even major events in the past get lost. Nuance gets lost. DNA tells one piece of the story, and archeology and written history tell other pieces.”

Advertisement