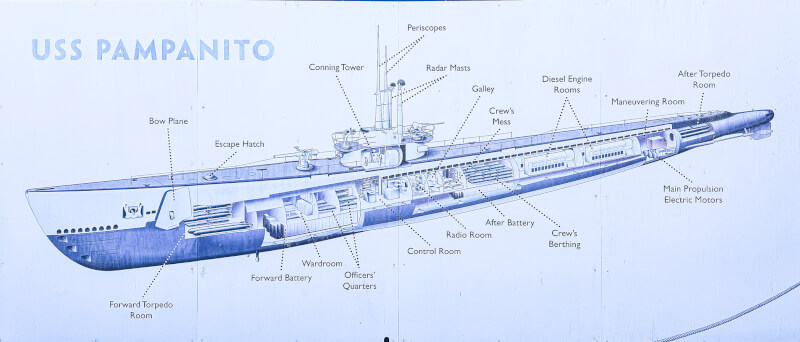

USS Pampanito sank six Japanese vessels—more than 27,000 tons of shipping—on six war patrols in 1944-45. It is now a museum boat tied alongside Pier 45 on Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Built in 1943 at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, USS Pampanito made six war patrols, sank six Japanese ships, damaged four others, and barely survived a sustained depth charge attack on its maiden voyage.

Named for the pompano fish, the 95-metre Balao-class diesel-electric submarine narrowly escaped a double torpedo strike, rescued 73 Allied prisoners of war, and earned six battle stars for WW II service.

Crewed by 10 officers and 72 enlisted men, Pampanito is a classic example of the boats of the so-called silent service, similar in design to the German U-boats that plied the North Atlantic in their efforts to deny Allied forces in Europe and Africa critical equipment, supplies and manpower.

The Allied submarine war against Japan created a blockade that denied the Empire oil, iron ore, food and other raw materials needed to continue to fight.

Comprising less than 16 per cent of American naval personnel at the time, U.S. submarines sank more than 600,000 tons of enemy warships and more than five million tons of merchant shipping (‘tons,’ as they relate to shipping, is a nautical term referencing a vessel’s cargo capacity, not its weight or displacement).

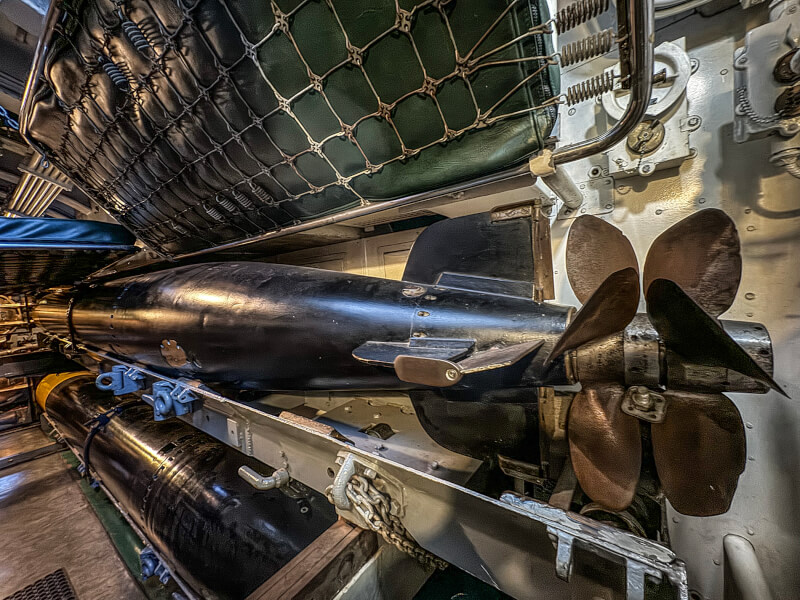

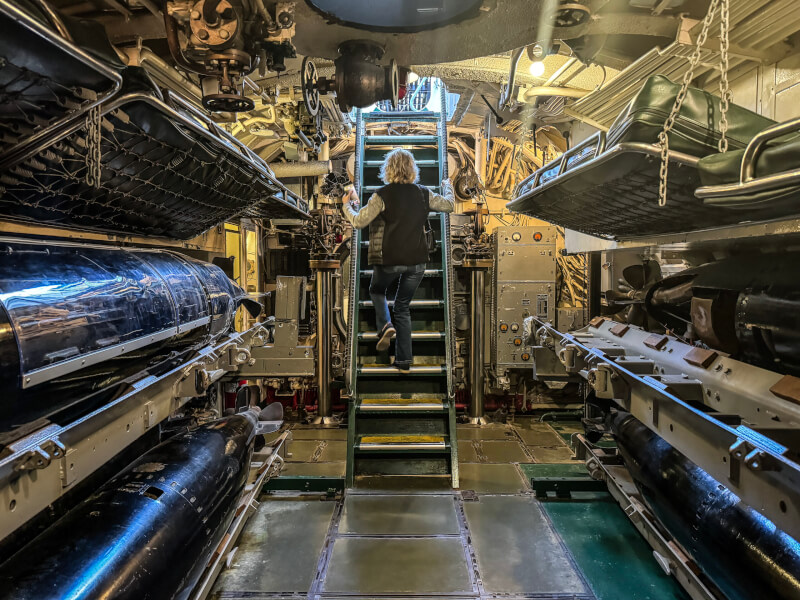

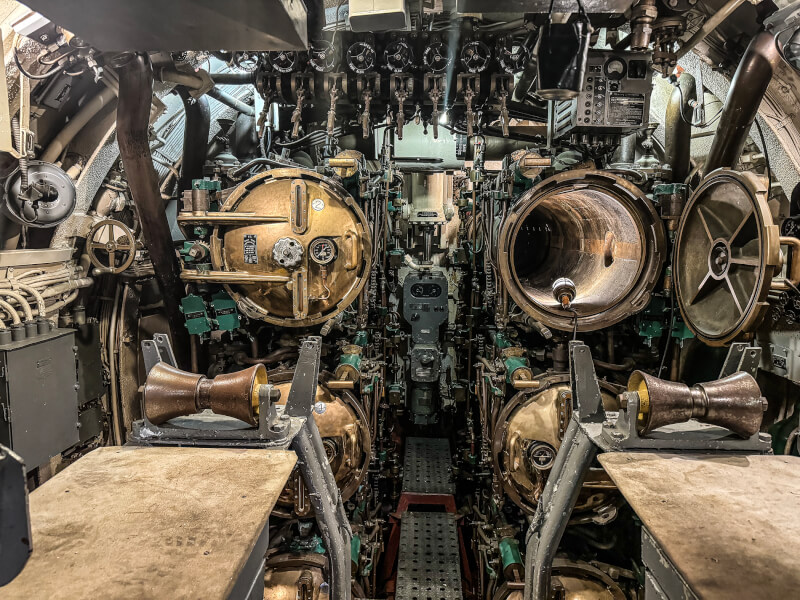

The four stern torpedo tubes aboard Pampanito look almost as good as the day the boat was commissioned in November 1943.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The last American sub sunk during WW II was USS Bullhead, lost to depth charges from a Japanese plane the day the Americans dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima—Aug. 6, 1945. The war ended nine days later.

By comparison, the Kriegsmarine lost 793 U-boats; 75 per cent, or 28,000 German U-boat crew did not survive the war.

In U.S. navy tradition, missing submarines are officially declared “overdue, presumed lost.” They remain on “eternal patrol.” The designation derives from the fact that submarine patrols begin at departure from port and end on their return. Hence, the patrol for a sub that sinks never ends.

Pampanito was decommissioned in 1945, served as a naval reserve training vessel from 1960-1971, and was made a memorial and museum in 1975. The boat was declared a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1986 and is now owned and operated by the San Francisco Maritime National Park Association.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Based at Pearl Harbor, Pampanito conducted six patrols off Saipan, Guam, Formosa, China and the Japanese main islands, in the Pacific, South China Sea and Gulf of Siam. Pampanito’s longest patrol ran 63 days; its shortest was 20. “Diesel oil—all of your clothes, the whole [boat] smelled of diesel fuel,” recalled one veteran in an audio tour of the boat. “Wherever I was, they knew a submarine sailor by the smell.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Every square inch of space aboard submarines is at a premium. Like their brethren in navies the world over, Pampanito crew bunked all over the boat, even in the torpedo rooms. “I had as bedfellows, a torpedo on one side and a torpedo above me,” said another crewman.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Pampanito packed 24 torpedoes, with six 533mm torpedo tubes forward and four aft. These are Mk XIV steam torpedoes with two speed settings, 31 and 46 knots. Pampanito also used Mk XVIII electric torpedoes, which were quieter but, at a top speed of 29 knots, slower.[Stephen J. Thorne]

There’s no life like the submariner life. With up to 85 crew aboard and just four heads, or toilets, there wasn’t much opportunity for privacy. “Submarines are tight quarters and we all lived together,” said a Pampanito veteran. “Sometimes you’d have to wait. That’s all there is to it.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

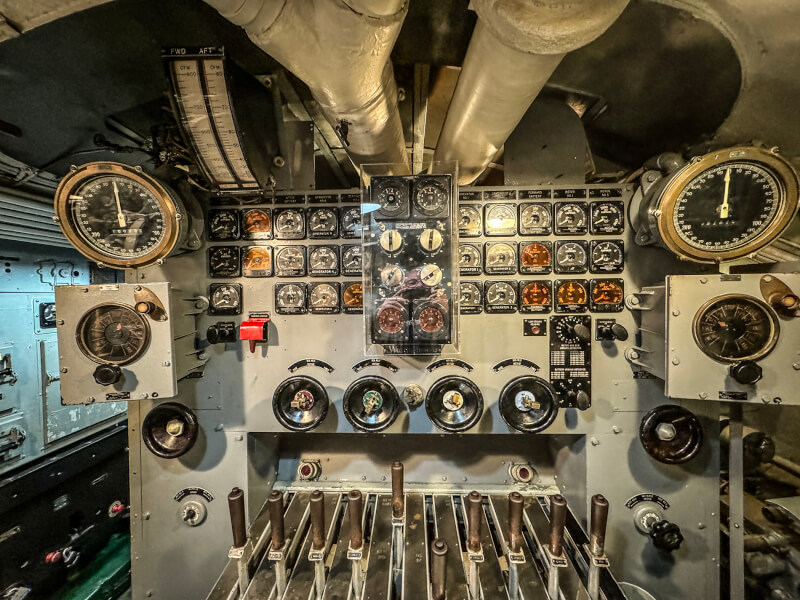

The boat’s maneuvering room with the propulsion control stand. The levers switched the electricity from the boat’s generators to charges batteries or to power its main propulsion motors.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

“All ahead one third.” “Charge the batteries.” The orders would come down from the bridge.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Two men, port and starboard operators, would operate the main control cubicle. “We had control of the speed of the engines, how the electricity was taken from the generators either to the batteries or the main motors,” said Electrician’s Mate O.D. Hawkins

[Stephen J. Thorne]

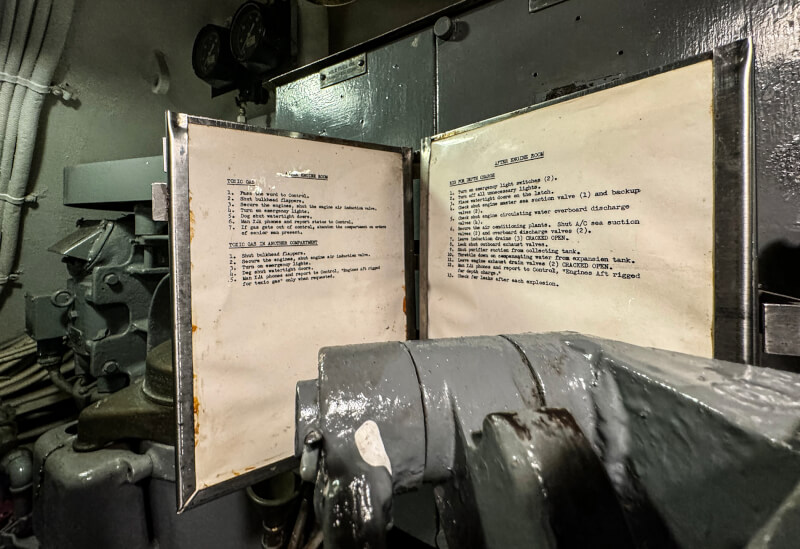

Like an aircraft pilot’s checklist, procedures were documented in detail. The boat surfaced to recharge its batteries nightly.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

[Stephen J. Thorne]

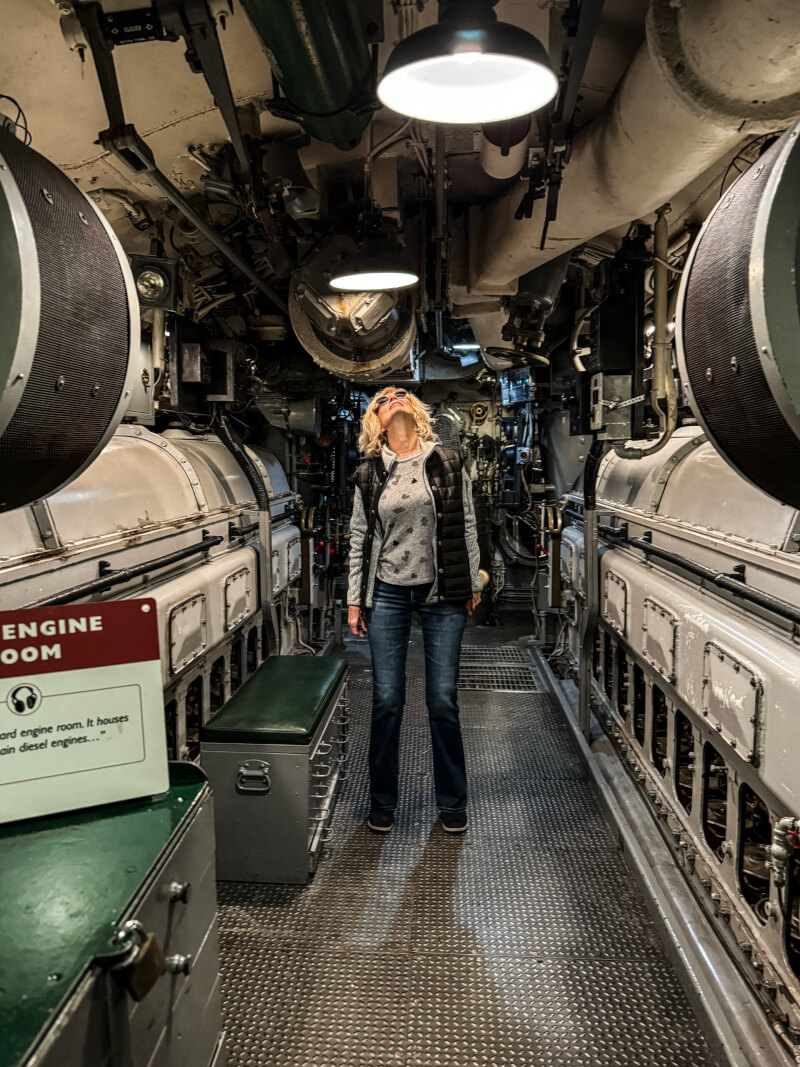

Pampanito’s aft engine room, immediately behind the forward engine room, contained two of the boat’s four main engines. Top surface speed was 21 knots (24 mph). It was one of the loudest areas of the boat. “Submarines are noisy,” said one crewman. “The noise levels at that time were so high that you basically couldn’t hear anybody talk. You said everything by signal—everything.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Part of the crankshaft on the starboard engine.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The engines ran hot and would be shut down as the boat submerged. “I used to absolutely detest going down on a dive after we’d been running on the surface for six to eight hours with all four main engines online,” said Radar Technician George Moffat, “because by then the boat was hot, the engines were hot and, with no ventilation, guess where all that engine heat came—throughout all the rest of the boat. And it would get hot.”

[ Stephen J. Thorne]

Evaporators made the boat’s fresh water by distilling seawater. “Generally, you made the water when you were on the surface only,” said a veteran. “The No. 1 priority for water aboard the boat was always the battery. If there was any left over, we had it for cooking and coffee and then, probably lowest on the list was shower.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

“We couldn’t bathe very often,” said another. “Water was at a premium; showers were not frequent. It must have been, like, 10 days to two weeks. You used a minimum of water.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

“We took baths, you know. You could get a pale of water—cold water.” The cooks, bakers and motor machinists got priority when there was bathing water available. The bathing areas were used for food storage when the boat first left port. “We all smelled.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Each man was assigned a tiny locker next to their bunks. They would often zip their uniforms into their mattresses. They would usually wear T-shirts, shorts and sandals on sea duty. This is the officers’ quarters, located forward of the enlisted area.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The crews’ mess, with chess/checker and backgammon boards built into the tables for recreational time. The crew that was relieving the watch would eat first. The crew coming off the watch would then take their turn before bunking down. They even had movies, which they’d watch over and over again. “We had records that we played, and the radio,” said one crewman. “That’s all you had. I remember listening to Tokyo Rose. She was telling us that so-and-so was sunk and ‘we’d be catching you,’ you know.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The galley. “I worked, let’s say, from 5:30 in the morning until 6:30 at night,” said Boat’s Cook Joseph Eichner. “Breakfast was French toast, fried eggs, bacon, and sausages. Noon meal, we’d have pork chops or ham or chicken or steak. We usually had French fries. And when you fed the whole crew—85 men—you had to peel a lot of potatoes.” The baker baked cakes, cookies and rolls aboard the boat well into the night. Coffee was available 24 hours a day.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

An escape hatch midships.

[ Stephen J. Thorne]

[Stephen J. Thorne]

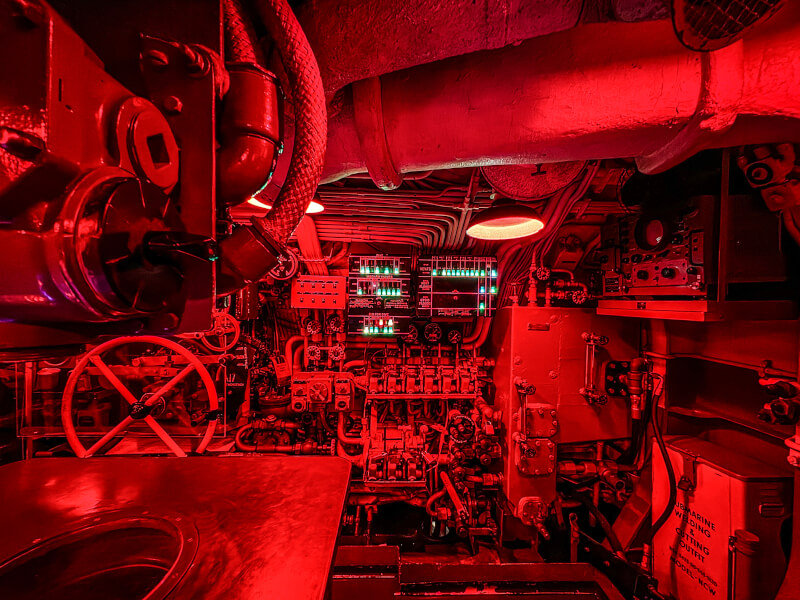

The red lights were for the benefit of sailors standing nighttime lookout watches.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The “Christmas tree” was a red-and-green lighted panel in the control room indicating the status of the hull openings—flood ports in the bottom of the ballast tanks and vents that allowed air to escape out the top as seawater flooded and submerged the sub. The wheel to the left was operated by the planesman, who controlled the pitch and depth of the sub. Pampanito was rated at 450 feet.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

LIFE Magazine and National Geographic were standards of the day.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

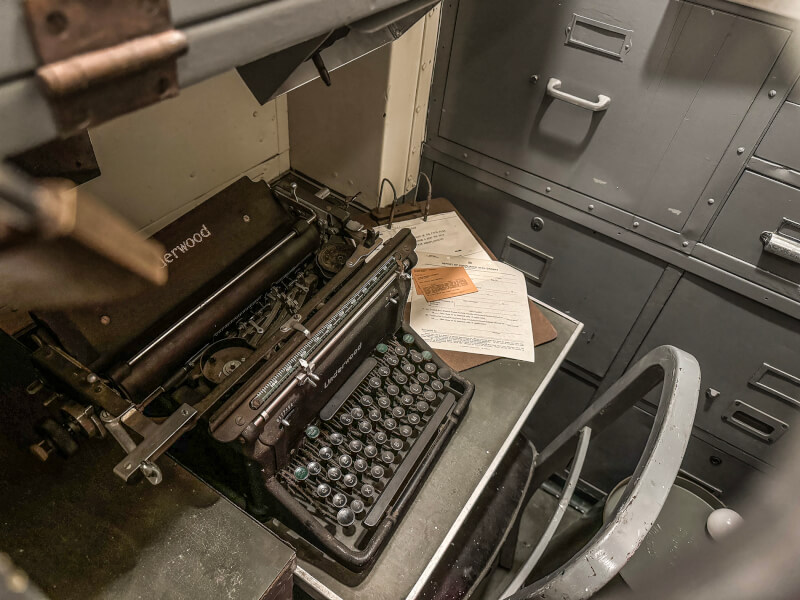

The office. Chief Yeoman Charlie McGuire’s workplace McGuire was the boat’s clerk. “I knew everybody aboard,” he said. “It’s a very good rate, yeoman.” Added another crewman: “The yeoman probably knew more than the officers did. The yeoman typed everything that went out of that ship and he read all of the official mail that came in.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The officers’ wardroom, where they ate, conducted meetings and passed the little free time they were afforded. “I don’t remember there being a cross word between the officers,” said Radar Officer Richard Sherlock a navy lieutenant. “Most off us, back and forth, used our first names. I’m sure the crew had nicknames for all of us that they didn’t use in our presence.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Sleeping with torpedoes.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

There are six forward torpedo tubes.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Pampanito’s steel deck.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

The boat’s 102mm deck gun was located aft of the conning tower.

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Note the broom on to of Pampanito’s forward mast, indicating a “clean sweep.”

[Stephen J. Thorne]

Advertisement