Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through, the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

—from “Dulce Et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen

“The very essence of spring was in the air,” wrote Canadian Lieutenant-Colonel George Nasmith about Belgium’s Ypres salient on April 22, 1915. “I felt as if I had to go out into the open and watch the birds and bees, loll in the sun, and do nothing.”

An analytical chemist from Toronto, the 4′ 6″ intellectual had been deemed ineligible for combat service due to his small stature. Undeterred, he had instead received authority to organize a laboratory for testing the troops’ drinking water.

On April 22, having travelled close to the Allied front line “to see what ‘No Man’s Land’ was like,” Nasmith ran into his friend Captain Francis Scrimger, the medical officer of the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment). Sharing pleasantries, he and another comrade eventually pushed on until “our attention was attracted to a greenish yellow smoke ascending from the part of the line occupied by the French.”

Without any sense of urgency, both lit cigarettes and observed the expanding cloud as it drifted forward at roughly eight kilometres an hour. It was only after Nasmith noted that it contained streaks of brown that he grew more concerned.

“That must be the poison gas that we have heard vague rumours about,” he surmised as the reality dawned on him. “It looks like chlorine, and I bet it is.”

And it was coming straight for them.

The sight was horrifying—if a somewhat expected horror.

Essentially outlawed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, neither the Central Powers nor the Entente were outright opposed to the use of poison gas. An ambitious Germany, however, was the first to act on it on a large scale.

Experiments with weak irritants had previously fallen short of expectations. German chemist Fritz Haber then stepped up with the idea of using chlorine. Moreover, to circumvent the convention’s stipulation that gas must not be fired from exploding shells, he suggested releasing it through trench-installed hoses.

The intended target would be the Ypres salient. Considered a symbol of Allied tenacity, the front there jutted into German territory and acted as a buffer zone for the logistically critical Channel ports. Eliminating the salient would have enveloped as many as 50,000 Entente troops, including the relatively fresh and largely inexperienced 1st Canadian Division that defended part of the line.

There were other motivations, but fundamentally, the first mass use of lethal chemical warfare was perceived as a means to break the deadlock on the Western Front. Combined with artillery barrages and numerically superior forces, the Germans hoped that gas could eradicate the proverbial thorn in their side.

The Canadians were barring the way by mid-April 1915, wedged between the British 28th Division on the right and North African infantrymen of France’s 45th (Algerian) Division on the left. The formation’s overall command fell to British-born Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson. Nevertheless, its three infantry brigades were led by Canadians: brigadier-generals Malcolm Mercer (1st Brigade), Arthur Currie (2nd Brigade) and Richard Turner (3rd Brigade), the latter a Victoria Cross recipient for actions during the Boer War.

As the enemy installed more than 5,730 steel canisters brimming with 160 tonnes of chlorine behind parapets and sandbags and waited for the right moment to turn on the taps, the Allies tried to confront the growing evidence of what was to come.

The three infantry brigades of 1st Canadian Division were led by brigadier-generals Arthur Currie, Malcolm Mercer and Richard Turner. [Wikimedia/LAC/PA-001370; Canadian Virtual War Memorial; DND/LAC/3221891]

On April 13, German Private August Jäger deserted to the French lines, where he revealed information about the cylinders. He further explained that the enemy’s upcoming offensive would be signified by three red flares dropped from an aeroplane, even handing his captors the rudimentary gas mask he had received—essentially comprising a piece of fabric soaked in a mildly protective solution.

“That must be the poison gas that we have heard vague rumours about. It looks like chlorine, and I bet it is.”

A second deserter told a similar story two days later, news of which reached the Canadians. In response, Major Andrew McNaughton of 7th Battery, Canadian Field Artillery, received permission to launch 90 rounds toward the German trenches as a probing measure to uncover the gas. It proved unsuccessful.

Nervous anticipation built during the subsequent days until finally, if devastatingly, a German spotter plane fired the three red flares on the 22nd. With it came an intense artillery bombardment against the Entente lines and the city of Ypres itself. Worse, at around 5 p.m., the cloud of gas emerged, bolstered by an advantageous wind.

It was, in the eyes of Fritz Haber, “a way of saving countless lives.”

German Sergeant Leisterer watched the hundreds of gas canister valves open with morbid fascination. Following a distinctly ominous hissing noise, the soldier of Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 233 then watched as the “whitish gas drifted from the long tubes over the parapet. Soon it took on a yellowish green colour, rolling in an interminable cloud, sneaking across the earth towards the [Entente] trench.”

The monstrous haze, stretching some six kilometres and reaching up to 30 metres high in places, seeped into every crevice, penetrating shell hole after shell hole before rolling through the 45th Algerian and 87th French Territorial defences.

“One had a sensation as if some beautifully horrible natural event was taking place,” recalled Leisterer of the sight. “The impression was tremendous.”

In reality, the effects were as heinous as they were almost instantaneous. Inhaled fumes damaged and destroyed the alveoli—tiny air sacs in the lungs—and caused fluid discharge that impaired oxygen exchange. The chlorine mixed with these bodily fluids and water vapour to form tissue-burning hydrochloric acid.

Victims began to drown within themselves, seared from the inside out. Screaming and begging for mercy, some French and North African soldiers dropped their rifles and fled only to drag out their misery by running in the wind’s direction; others writhed on the ground in agony, choking and vomiting greenish slime.

“Their eyeballs [were] showing white,” described McNaughton as a six-kilometre gap opened in the Entente line. “They literally were coughing their lungs out.”

Nine Canadian artillerymen who had been in the Algerian sector were killed, their fate a slow and ugly one amid the lethal cloud.

Elsewhere, entire Canadian battalions had mere minutes to prepare for their own dose, although the gas had gradually dissipated by that stage, sparing most from its deadliest effects. Despite this, irritated eyes were still rubbed raw as blurry, yet unmistakable, figures appeared on the horizon. The Germans were advancing.

And it was up to 1st Canadian Division to stop them.

The enemy threat was met by force, dashing German expectations that the Ypres salient would fall with ease after unleashing their not-so-secret weapon.

The Canadians, together with surviving Algerians, fought on.

Among those in the firing line were the men of 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), who quickly shifted their defensive axis to plug the gap on their flank. Aside from a few overrun positions, the outnumbered troops held their ground.

Back at 3rd Infantry Brigade headquarters, an increasingly disorientated Brigadier-General Turner struggled to maintain order. The VC holder was proving to be the wrong man for the hour. Orders from his HQ, which was also under fire, sometimes varied from panicky to confused to entirely out of touch with events on the ground. Unfortunately, his shortcomings were most felt by the troops engaged at the front.

Those same soldiers, still retching from the gas, learned to rely less on brigade-level instructions and more on the men beside them on the parapet. Fighting in often isolated and desperate pockets, the Canadians struggled to turn the enemy tide.

In such dire circumstances, the heroics of individual soldiers—both seen and unseen—occurred throughout the salient. Nineteen-year-old Lance-Corporal Fred Fisher was but one example. The 14th Battalion machine-gunner had poured rounds into the German ranks since the attack had commenced. When all other crew members were killed, the St. Catharines, Ont., native refused to retreat. In doing so, Fisher bought time for the Canadian artillery to withdraw to safer positions.

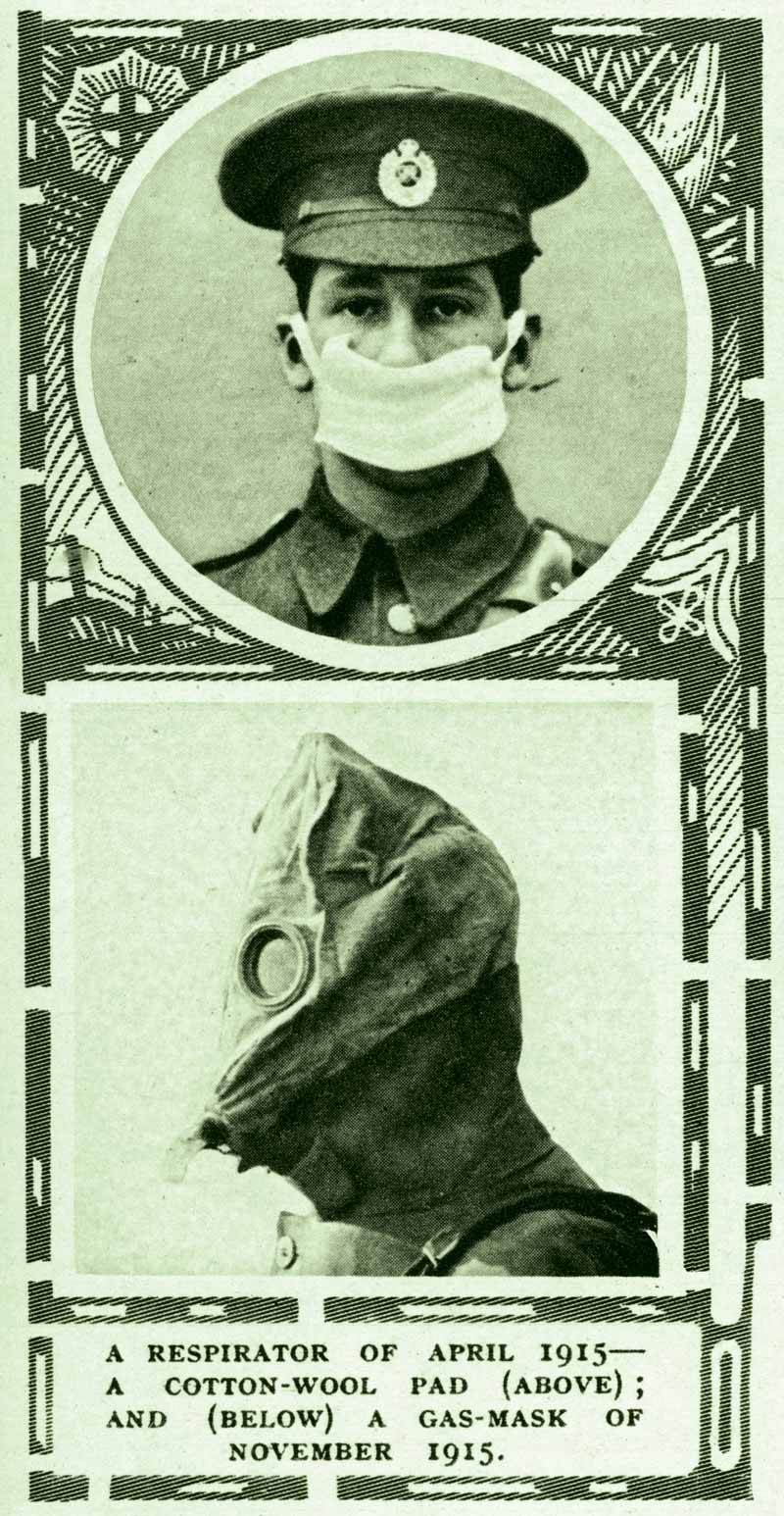

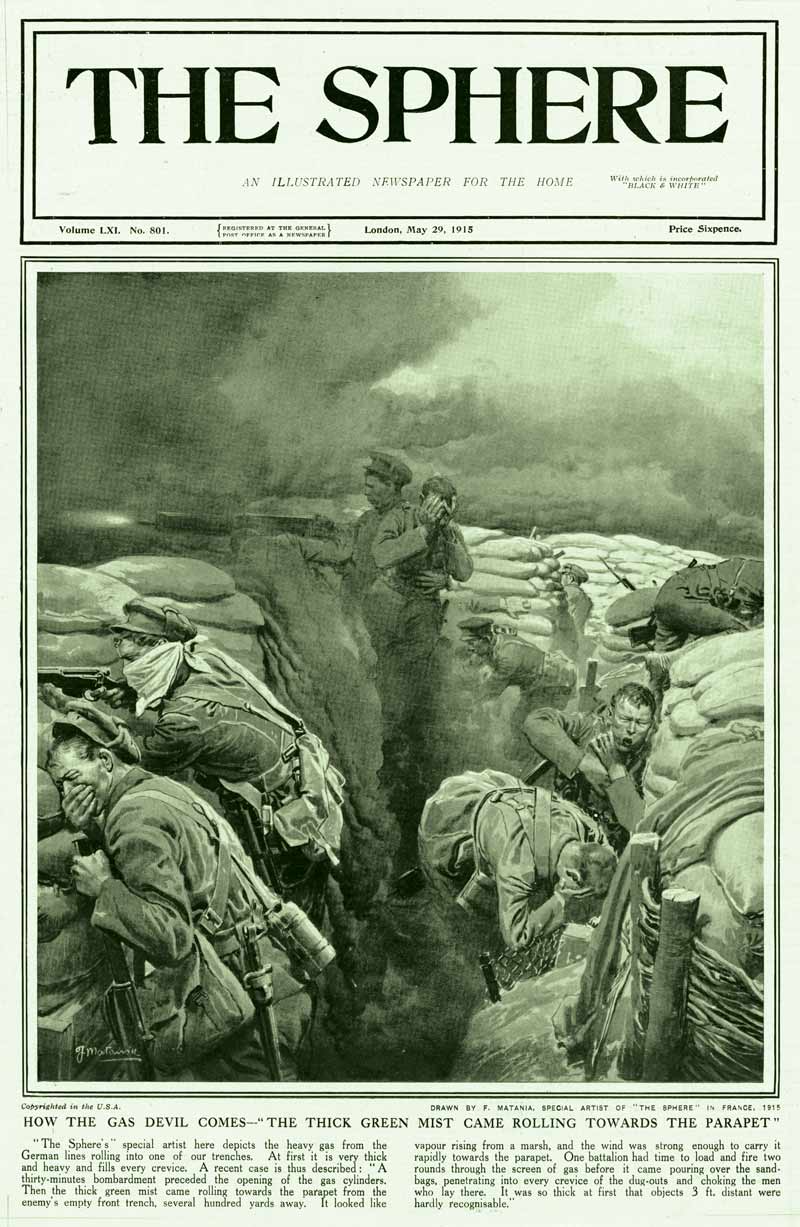

The cover of a late May 1915 issue of British newspaper The Sphere depicts gassed troops in the trenches.[Chronicle/Alamy/2M3NTNN]

He was later killed in the battle, his body never recovered. He received the Victoria Cross for his actions, Canada’s first of the war. Three more VCs were presented to Canadians for efforts at Second Ypres. Deserving though each recipient was, many brave acts went unnoticed, unrecorded and unrewarded.

Alas, German inroads were still being made, notably at Kitcheners Wood where enemy forces had seized several British guns. From midnight on April 22-23, the 10th and 16th battalions counterattacked in an audacious yet flawed offensive.

Advancing in the dark, the 1,600-strong force encountered an unmarked fence within sight of the strongpoint objective. The men overcame the hurdle, but not without alerting its German occupiers.

Flares, then muzzle flashes, illuminated the Canadian soldiers caught out in the open. Enduring a hail of small-arms fire, the two battalions launched a bayonet charge, sustaining horrendous casualties until they reached the forest. Survivors took few prisoners, but they did recapture four British artillery pieces. The Canadian defence of Kitcheners Wood would continue to be a bloodbath.

Another scene of devastation took place atop Mauser Ridge, a German-held position overlooking the entire battlefield. Brigadier-General Mercer’s 1st and 4th battalions were tasked with dislodging its enemy defenders. When French support failed to materialize, however, the 6 a.m. assault on April 23 descended into chaos, with the Canadian troops having to cover around 1,500 metres in broad daylight.

“Ahead of me I see men running,” recounted 1st Battalion’s Private George Bell. “Suddenly their legs double up and they sink to the ground. Here’s a body with the head shot off. I jump over it. Here’s a poor devil with both legs gone, but still alive.” More than 900 casualties were sustained during the doomed attack.

Command miscalculations aside, the Canadian infantry was having to deal with the ever-inefficient Ross rifle, a weapon prone to jamming that could fail men at the least opportune moment—usually after rapid-firing in the heat of battle. It wasn’t uncommon for troops to discard these rifles, replacing them with British Lee Enfields or even German Mausers when available. Most weren’t so lucky, left to hope that their primary source of protection would hold out.

By nightfall on April 23, the Entente overall—and the Canadians, in particular—were also holding out. There had been gains and losses, tactical victories and defeats, but Ypres remained in friendly hands for the time being. With British reinforcements having plugged gaps in the line, all was not yet lost. Even German prisoners appeared to express grudging respect for their adversaries, one of whom later remarked to his Canadian captors: “You fellows fight like hell.”

Armed with chemistry, Lieutenant-Colonel Nasmith—still suffering from the gas attack on the 22nd—found a different means to fight.

Being caught in that menacing cloud had come with its upsides, if only from a purely scientific perspective, as he was now inclined to believe that chlorine had been combined with “perhaps an admixture of bromine” as an extra irritant.

Through coughs and splutters, Nasmith reported his findings to Allied officials, becoming the first person to formally identify the gas’ chemical compounds.

He wouldn’t be the last to gain such insights borne of first-hand experience.

At around 4 a.m. on April 24, the Germans launched a second gas attack against the Canadian lines, primarily directed at 8th and 15th battalions. The blanket of death was smaller yet denser than before, but it was also widely anticipated.

Canadians with scientific backgrounds, having seen brass buttons tarnished green two days earlier, warned that the discolouration could result from chlorine. Soldiers familiar with the smell of chlorinated water in tea-making were just as capable of identifying the substance. Jointly, these independent intuitions left men scrambling for improvised respirators, typically a cloth or handkerchief soaked in ammonia-rich urine to neutralize hydrochloric acid. Anyone unprepared or unwilling to perform such an unpleasant act of self-preservation risked an agonizing death.

This crude method saved most—but not all—victims, with many survivors plagued by health challenges for the rest of their shortened lives. More pressing was the German horde again advancing toward the battered and bruised defenders.

Canadian formations throughout the salient offered a stout resistance, ensuring the enemy paid for every inch of ground. Yet slowly, incrementally, the sheer weight of German opposition became overwhelming as some gassed troops began to buckle.

Communications had broken down. So, too, had much of the command structure. And while there remained strongholds, the floodgates had opened.

The situation wasn’t helped by Brigadier-General Turner, who, in his battle-fatigued state, misinterpreted divisional orders and pulled his men back amidst a bitter struggle. Unable to disengage the enemy as they withdrew, the Canadians were thrust into a maelstrom and harassed further in new, weaker positions.

But for every folly, there was heroism. Lieutenant Edward Bellew, the 7th Battalion (1st British Columbia) machine-gun officer, played a vital role in the fighting retreat. Disregarding his own wounds, he and a comrade spat rounds into the German force until his loader was killed and he ran out of ammunition. Bellew next destroyed the spent weapon under fire, retrieved a rifle with bayonet attached, and charged at the enemy, somehow surviving to be captured. He earned the Victoria Cross.

Like falling dominoes, 3rd Brigade’s withdrawal mounted pressure on Lieutenant-Colonel Currie’s 2nd Brigade, prompting its commander to make the controversial decision of leaving his men to personally request British assistance. Destined for greatness later in the war, his judgment on April 24 was, and is, hotly debated.

Without question was the extraordinary loss suffered that day, with estimates suggesting that 3,058 Canadian casualties were incurred in just 24 hours.

And the battle wasn’t over.

Human endurance had been pushed beyond its limits by April 25 as the Canadians, sleepless for several days, continued to withstand repeated assaults. One by one, however, the battalions were relieved by Allied reinforcements.

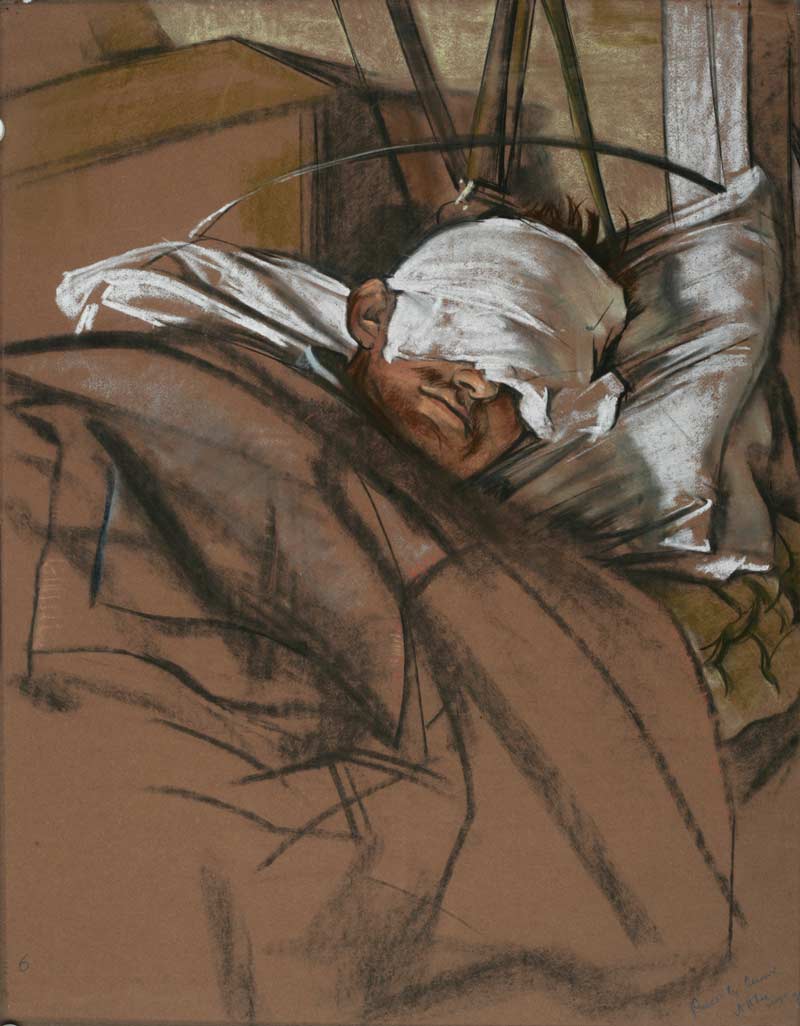

Artist Eric Kennington depicts a blinded soldier recovering from the effects of mustard gas.[Eric Kennington/CWM/19710261-0332]

Anyone unprepared or unwilling to perform such an unpleasant act of self-preservation risked an agonizing death.

Blood-stained and prone to coughing fits, the men departed a battlefield that would never truly depart them—physically, mentally and in an entire country’s collective consciousness, where the Second Battle of Ypres would eventually stand with the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele as a symbol of Canadian fortitude. In holding the line, these men had sacrificed much for a salient far from home.

“When the people of the little villages through which we passed saw the name ‘Canadian’ on our car,” remembered Lieutenant-Colonel Nasmith, “they nudged each other and repeated the word ‘Canadian.’ It was the name in everybody’s mouth those days, for it was now general knowledge that the Canadian division had thrown itself into the gap and stemmed the German rush to Calais.”

It had come at a cost of 6,036 Canadian dead, wounded and captured.

Survivors left behind friends, comrades and parts of themselves they could never retrieve. For John Armstrong of 3rd Canadian Field Artillery, the horrors he encountered were encapsulated by a lone, injured horse walking past “with just the lower part of a man’s body in the saddle. From the waist up there was nothing.”

Further horrors lay ahead before the battle ended on May 25, 1915, by which point numerous individual engagements had taken their toll on the Entente forces. For Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, that month’s Battle of Frezenberg became a particularly harrowing clash when the unit was almost annihilated in defence of the Ypres salient. Nevertheless, like the Canadian veterans of the April struggle, they, too, held out with great distinction.

More immediately, the incessant strain placed on Canadian medical staff was a battle unto itself. Despite poison gas having presented unique challenges for doctors and surgeons, conventional injuries from small arms-fire and shrapnel were far more prevalent at dressing stations behind the front line.

“There were some bad wounds—legs and arms crushed and heads torn open,” wrote Captain Scrimger, the medical officer who had been with George Nasmith prior to the first gas attack and who, for the remainder of the battle, attended hundreds of patients without rest. On April 24, having learned that hundreds more lay dying in forward positions, the doctor went to them.

Scrimger saved lives well into the next day, all under heavy fire, until his position became untenable, leaving him with little choice except to evacuate the wounded. When one injured captain couldn’t be transported, Scrimger stayed with him as artillery fire edged closer, setting the building ablaze. The slight medical officer carried the soldier away, past enemy patrols, to the relative safety of another aid station. His gallant efforts were later acknowledged with the VC.

Courage came in many forms during the Second Battle of Ypres, from the privates in the trenches to the gunners and stretcher-bearers in the field. Mistakes had been made, but almost all the Canadians had stood tall in their first major fight of the war.

Each soldier found ways to cope with what they had experienced. For Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, mourning the loss of a friend, it was in writing a soon to be famous poem.

Sisters in sorrow

by John Boileau

Among the families impacted by the more than 6,500 Canadian casualties during the Second Battle of Ypres were the Braithwaite sisters of Hamilton: Marjory, Mary and Dorothy. Two of the trio married officers in the First Canadian Contingent.

Marjory married Lieutenant Trumbull Warren, a Royal Military College graduate, president of Toronto’s Gutta Percha & Rubber company and member of the 48th Highlanders of Canada. Trumbull went overseas with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) as a captain and the unit’s adjutant.

Mary wed Captain Guy Melfort Drummond, the son of wealthy Montreal industrialist George Alexander Drummond, a partner in Redpath Sugar. The younger Drummond was a successful businessman, too, and a prewar officer in Montreal’s Black Watch. When the war broke out, the newly married Drummond volunteered to go overseas as a member of the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada).

In England, Drummond voluntarily reverted to the rank of lieutenant to serve at the front. In April 1915, he was in Belgium’s Ypres salient as a company second-in-command. While their husbands served at the front, Marjory and Mary moved to England, a practice followed by many officers’ wives.

On April 20, after Canadian units had occupied positions along the Ypres salient, a huge German howitzer shell wounded Warren near Ypres’ Cloth Hall. He died shortly afterward. Drummond was allowed to attend his brother-in-law’s burial.

Drummond returned to the trenches on April 22, just as the Germans launched the Second Battle of Ypres. As he led an attack to close a gap in the line caused by the collapse of French colonial troops overcome by the first major gas attack, a bullet struck him in the neck. Drummond died instantly and today lies in Belgium’s Tyne Cot Cemetery.

Marjory and Mary became widows within two days of each other.

Their unmarried sister Dorothy sailed from Canada to offer support to her siblings. She travelled on Lusitania and marked her 25th birthday aboard on May 5. Two days later, the cruise liner was torpedoed by U-20. Dorothy survived in the water for a short time, but eventually drowned.

Her body was never recovered; a large stone cross marks her empty grave in Hamilton.

Three Canadian soldiers watch as a plume of smoke from an artillery shell rises above the rubble-strewn city of Ypres, Belgium. [Cyril Barraud/CWM/19710261-0021]

Marjory and Mary became widows within two days of each other.

During the Second World War, Marjory’s son, Trumbull, served in the 48th Highlanders. As a lieutenant-colonel, he was Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s personal assistant. Monty recommended Trumbull’s appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, noting “his reliability and devotion to duty have been outstanding.”

Marjory’s daughter, Margaret, married Gordon (Swatty) Wotherspoon. During the Second World War, he commanded The South Alberta Regiment when Major David Currie’s actions earned him the Victoria Cross at Saint-Lambert-sur-Dive during the Normandy Campaign. Wotherspoon later rose to brigadier-general and served as colonel commandant of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps from 1968 to 1973.

Marjory remarried and her 22-year-old son Lieutenant Douglas Snively, also a 48th Highlander, was killed in action in Italy leading his platoon to break through the Hitler Line in May 1944.

Throughout the Second World War, Marjory operated a canteen in Toronto for service personnel, for which she was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

Mary also remarried, to British Captain Tom Stoker, a relative of Bram Stoker of Dracula fame.

Advertisement