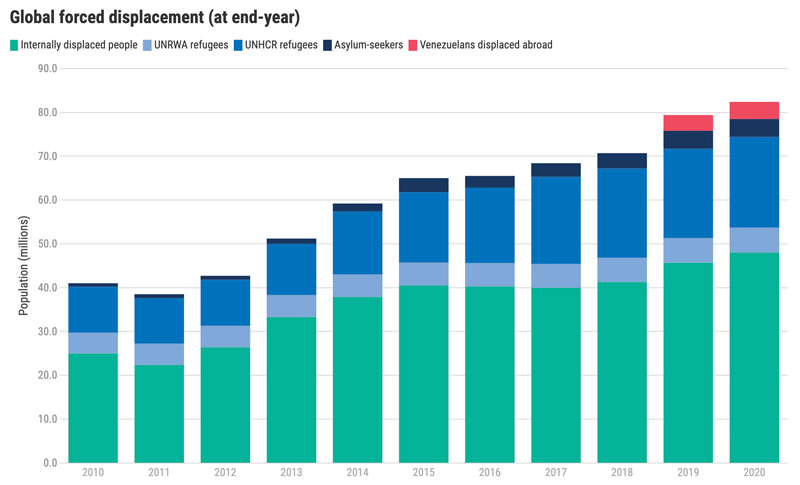

The agency says refugee numbers driven by violence, persecution, war and human-rights violations have been increasing for the past decade, rising by four per cent from 2019 to a record 82.4 million in 2020.

Almost a million children were born in displacement between 2018 and 2020.

Children under 18 are particularly affected, said the report. They account for 42 per cent of all forcibly displaced people despite the fact they comprise just 30 per cent of the world’s population. Almost a million children were born in displacement between 2018 and 2020, it said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the lives of those forced from their homes more difficult, both within and outside the borders of their native soil. More than 160 countries implemented border and travel restrictions last year.

“With many governments closing borders for extended periods of time and restricting internal mobility, only a limited number of refugees and internally displaced people were able to avail themselves of solutions such as voluntary return or resettlement to a third country,” said the report, released June 18.

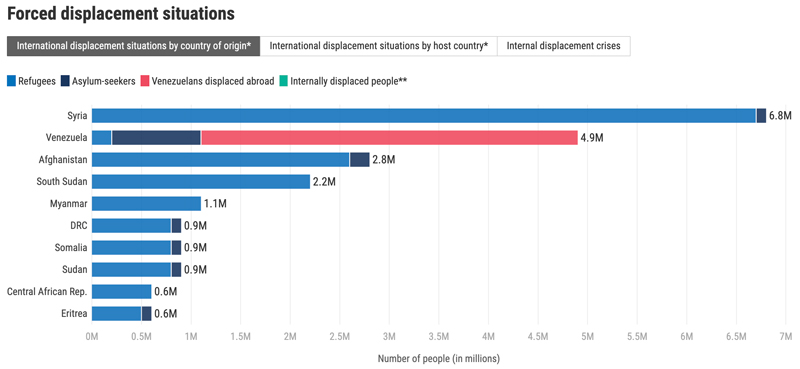

Basing its numbers on government, non-governmental organizations’ and its own data, the Geneva-based agency said Syria had the most displaced people as of Dec. 31, at 6.8 million, followed by Venezuela with 4.9 million, Afghanistan with 2.8 million and South Sudan with 2.2 million.

About 251,000 refugees returned to their countries of origin in 2020, the third-lowest number in 10 years. The report said continuing insecurity, an absence of essential services and a lack of work contributed to the decline.

Canada plans to bring in 45,000 protected persons this year.

The report pointed to areas of continuing conflict—notably Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Yemen and Ethiopia—and echoed calls for a global ceasefire.

“With numbers having risen to more than 82 million, the question is no longer if forced displacement will exceed 100 million people—but rather when,” said the report. “The need for preventing conflicts and ensuring that displaced people have access to solutions has never been more pressing than now.”

“Protected persons” is a legal term under international humanitarian law meaning people under specific protection of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and subsequent legislation.

Ottawa says it will offer asylum to more people in need, welcome more refugees through new channels, and increase support to community-sponsored refugees.

A federal government statement released the day the UNHCR report was published—two days before World Refugee Day on June 20—said it’s expanding a pilot project to welcome more refugees through “economic immigration streams.”

It said it would expedite processing of permanent residence applications for some program applicants, make it easier for participants to get settlement funds, waive fees for permanent residence applications, make the application process more flexible, and assist with immigration-related medical exams before entry.

“Currently, there are over 40,000 protected persons and their dependants residing in Canada with open permanent residence applications,” said the government report. “In 2021, almost 17,900 protected persons became permanent residents.”

In 2020, Secretary-General António Guterres repeatedly urged a drastic de-escalation of hostilities worldwide by year’s end. “The world needs a global ceasefire to stop all ‘hot’ conflicts,” he said.

The measure would help fight the pandemic and “create opportunities for life-saving aid, open windows for diplomacy and bring hope to people suffering in conflict zones who are particularly vulnerable to the pandemic,” the UN declared.

At least 180 countries, including Canada, along with the UN Security Council, peace advocates, civil society groups, regional organizations and millions of everyday people endorsed the call.

“The early months of 2021 have offered a glimmer of hope, even as conflict and displacement continue in many parts of the world,” said the agency report, citing a decision by U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration to admit up to 62,500 resettled refugees this year and as many as 125,000 in 2022.

“Many more such symbols of solidarity and responsibility-sharing are needed to fulfil the rights, needs and, where possible, hopes of the displaced people around the world.”

Turkey hosted the most refugees in 2020, at almost four million, 92 per cent of them Syrian. Colombia took in over 1.7 million displaced Venezuelans, while Germany hosted almost 1.5 million refugees, the bulk of them Syrians and asylum-seekers. At about 1.4 million each, Pakistan and Uganda rounded out the top five hosts.

These are for the most part temporary solutions. The bulk of refugees would naturally prefer to return to a safe and peaceful home country or resettle elsewhere. Resettled—another legal term—refugees have the right to reside long-term or permanently in their country of resettlement and may also become citizens of that country.

The UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration froze resettlement departures for several months last year amid early pandemic-related border and travel restrictions.

“We need much greater political will to address conflicts and persecution.”

Some of those restrictions were eased over time, but just 34,400 refugees were resettled to third countries in 2020, down from 107,800 the year before—a 69 per cent drop. The agency estimates 1.4 million refugees are in need of resettlement.

More conclusions from the UNHCR report:

- One per cent of humanity is displaced and there are over twice as many forcibly displaced people as in 2011, when the total was under 40 million.

- More than two-thirds of all people who fled abroad came from just five countries—Syria (6.7 million), Venezuela (four million), Afghanistan (2.6 million), South Sudan (2.2 million) and Myanmar (1.1 million).

- Eighty-six per cent of refugees are hosted by low- and middle-income countries and countries neighbouring crises areas. The least-developed countries provided asylum to 27 per cent of the total.

“Solutions require global leaders and those with influence to put aside their differences, end an egoistic approach to politics, and instead focus on preventing and solving conflict and ensuring respect for human rights.”

—

Read about the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre’s report on internally displaced persons here.

Advertisement