You may not know the name Frank Hurley but you almost certainly know at least some of his pictures.

Hurley was an Australian who left school at age 12, escaped the drudgery and hardship of a working-class life at the dawn of the 20th century, and turned his gift of gab and passion for photography into a lifetime of adventure and renown.

He sailed to Antarctica with Douglas Mawson and Ernest Shackleton, survived stranding in the frozen wasteland, documented both world wars and travelled the world. He was, in his heyday, a household name among his countrymen.

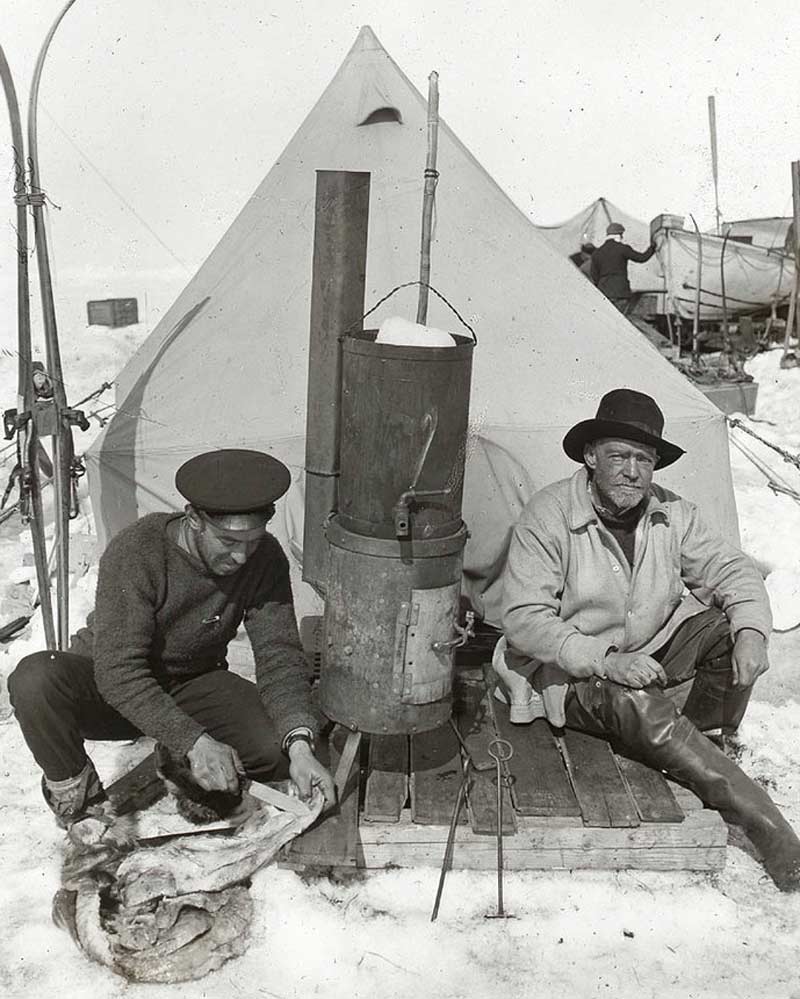

Hurley spent more than four years on Antarctic expeditions.

Working as a postcard photographer in Sydney, Australia, Hurley mastered the art of superimposing images from two or more negatives into one composite photograph.

He would later use the process, frowned upon today, to create striking First World War images arguably superior to anything anyone else was producing at the time. His most famous and largest composite photomural—“A Raid”—was first exhibited in London in 1918. It measured 6.1 by 4.7 metres.

“A Raid” was made up of 12 negatives and, printed in two parts, it measured 6.1 x 4.7 metres. It was displayed at Grafton Galleries in London in 1918. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was displayed at the Australian War Museum in Sydney with the title “A Hop Over.” [Frank Hurley/State Library of New South Wales]

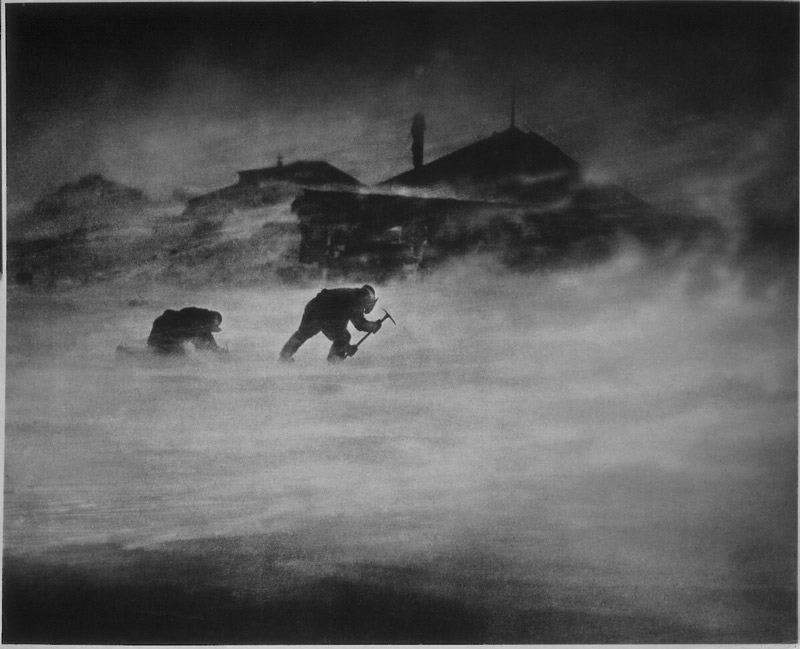

In a blizzard, Leslie Whetter and John Close of the Shackleton expedition get ice for domestic use from a glacier adjacent to their huts. [Frank Hurley]

Endurance makes its way through Antarctic ice. It was eventually frozen in and crushed by the ice. [Frank Hurley]

They were shocked to learn upon rescue that after two years the war hadn’t ended, it had escalated. Shackleton wrote that, they felt “like men arisen from the dead to a world gone mad.”

Months later, Hurley joined the Australian Imperial Force as an honorary captain and its second official photographer, taking unusual risks for photographers of the day and capturing stunning battlefield scenes during the Third Battle of Ypres.

Troops of the 1st Australian Division walk a duckboard track near Hooge, Belgium, on Oct. 5, 1917. [Frank Hurley/Australia War Memorial]

Hurley was technically the senior man on the battlefield, with Wilkins the designated assistant. In practice, they were independent equals doing different jobs. The official Australian war correspondent, Charles Bean, wanted Hurley to do the press work, taking pictures for day-to-day publicity and propaganda. Bean regarded these pictures of little long-term value. Wilkins was to be the official photographer of record, capturing the documentary evidence for future generations of where the Australian forces had been and what they had done.

The Canadian-born millionaire, Sir Max Aitken, owner of the London Evening Standard and the Daily Express, had already recognized photography’s potential.

Soon to become Lord Beaverbrook, Aitken set up the Canadian War Records Office in London in early 1916—a major influence in Bean’s decision to lobby for an Australian War Records Section, which was set up in May 1917.

Hurley said he was committed “to illustrate to the public the things our fellows do and how war is conducted.”

“Bean wanted pictures of every significant site, every battalion, battlefield and knoll they fought for,” wrote Australian film critic Paul Byrnes, a curator at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

“These were the more important pictures, because they would show the fields of battle before they changed in peacetime. This was close to an obsession with Bean, who had been immensely frustrated at the difficulties getting good photographs of the Australians at Pozières in 1916, and at Messines in 1917.”

At the outset of his wartime journey, Hurley said he was committed “to illustrate to the public the things our fellows do and how war is conducted.” His use of composite images landed him in trouble, however—even then, 80 years before digital photographs and Photoshop manipulations would ignite new controversies in the world of photojournalism.

In what today would be described as “photoshopping” his images to create “fake news,” Hurley constructed composite photomurals for the exhibition Australian War Pictures and Photographs. They were meant to convey the war’s drama on a scale not possible using conventional technology of the time.

Entitled “The Morning After the First Battle of the Passchendaele,” this composite shows Australian infantry wounded around a blockhouse near the site of Zonnebeke Railway Station on Oct. 12, 1917. Hurley added the sun beams and clouds from another photograph he had taken. [Frank Hurley/National Library of Australia]

In his diary for Nov. 20, 1917, Bean wrote with considerable annoyance that he had been told Beaverbrook “had seen Hurley’s work and wanted to take him in under his own control.… It looked as if Hurley had had an offer made to him by the Canadians—of all this we knew nothing whatever.”

“I told Beaverbrook that he clearly had us in his hand as far as the exhibition went—their exhibition killed ours,” Bean wrote. “The Canadians had had theirs—now they wanted to scoop in ours. We had no objection provided they gave us unlimited scope.

“But one thing we could not agree to was that they should control our photographers—we have our own policy, records and no ‘faked’ pictures except such as are clearly stated in their titles to be faked.”

The practice of manufacturing composite photographs was not limited to Hurley. Similar manipulations were conducted by Canadian, British and other First World War photographers. The Aussie just did them better than most anyone else.

Hurley and Bean fought bitterly over Bean’s assertions that composites diminished the pictures’ documentary value. Hurley even dressed in civilian clothes and eavesdropped on soldiers visiting his exhibitions, concluding by the favourable comments he heard that the composites were justified.

“None but those who have endeavoured can realize the insurmountable difficulties of portraying a modern battle by the camera,” he would later write for The Australasian Photo-Review. “To include the event on a single negative, I have tried and tried, but the results are hopeless.

“Now, if negatives are taken of all the separate incidents in the action and combined, some idea may then be gained of what a modern battle looks like.”

Bean nevertheless labelled Hurley’s composite images fakes, declaring “we will not have them at any price.” Hurley threatened to resign his commission—according to some reports, he did.

By chance, however, he met Sir William Birdwood, general officer commanding the Australian Imperial Force. Birdwood was dismayed at Hurley’s intentions to quit and brokered a compromise: Hurley could print six composite photographs if he would continue as the force’s official photographer. Hurley agreed. Bean grudgingly went along.

After a stint in Palestine where he embraced the common practice at the time of setting up a significant number of photographs, Hurley left the front for good in March 1918. The composites only ever accounted for a fraction of his wartime work.

Private John (Barney) Hines is surrounded by German equipment looted during the Battle of Polygon Wood in September 1917. He is counting money stolen from prisoners of war and is wearing a German army field cap. He is surrounded by his collection of German weapons and personal equipment. [Frank Hurley/Museums Victoria]

It seemed that Hurley just rubbed Bean the wrong way. The historian also resisted Hurley’s tendency to stage and, to his mind, misrepresent photographs and scenes.

“And he objected to Hurley’s self-promotion,” said Jackson. “Bean accused him of taking credit for Wilkins’s work and feared that the work of the Australian War Records Section would be overshadowed by Hurley’s self-interested publicity.

“This comes down to different personalities—Hurley the flamboyant showman, Bean the cautious—perhaps overcautious—chronicler.”

Hurley’s images, along with those of British, Canadian and other Australian photographers and artists, were exhibited in London’s Grafton Galleries from May to September 1918. Hurley organized the selection and printing of his photographs, choosing four composites.

“His single-capture images and his composites are simply extraordinary,” wrote Milan Scepanovic, picture editor of The Australian national newspaper in an article entitled “The Camera Doesn’t Lie” on April 9, 2021.

“It is incredible that he could use such bulky, heavy equipment during scenes of brutal conflict.… Then to have the care and professionalism to keep his precious photographic plates dry and light-tight so they could make the journey back from the front, be transformed with chemicals and emerge from the darkroom as permanent records for generations to come.”

Despite their differences, Bean ultimately respected Hurley’s commitment to the craft, writing that Hurley “is a splendid, capable photographer. I was worrying that he might miss the best pictures but he always got there, without fuss.”

Under Bean’s direction, the Australian War Records Section collected 11,243 negatives depicting the activities of Australian forces across Europe and the Middle East.

“Everywhere the ground is littered with bits of guns, bayonets, shells and men.”

Aitken also established the Canadian War Memorials Fund, which evolved into a collection of artworks by premier artists and sculptors in Britain and Canada.

Hurley’s contributions were not limited to photography and film. His diaries left a literary legacy describing the horrors of war.

“The exaggerated machinations of hell are here typified,” he wrote from the trenches. “Everywhere the ground is littered with bits of guns, bayonets, shells and men. Way down in one of these mine craters was an awful sight.

“There lay three hideous, almost skeleton decomposed fragments of corpses of German gunners. Oh the frightfulness of it all. To think that these fragments were once sweethearts, maybe, husbands or loved sons, and this was the end.”

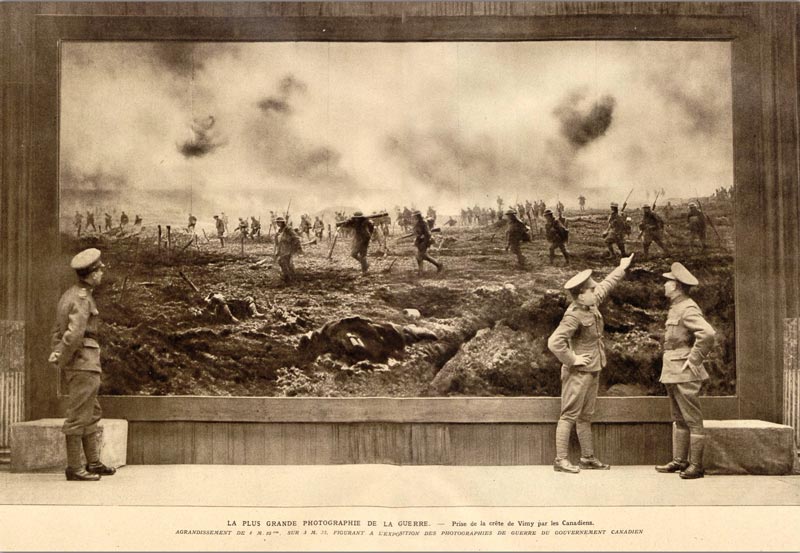

Billed as “the biggest photo of the First World War,” William Ivor Castle’s composite photograph “The Taking of Vimy Ridge” was first exhibited with other Canadian war photographs in London in 1917. At 6.1 metres by 3.35 metres, however, it was not as big as Hurley’s “A Raid.” A masterpiece for its time, the piece was printed in five sections and took five hours to frame. Castle, an official British photographer assigned to the Canadians, shot the image on April 9, 1917.

Hurley went on to photograph an expedition to Papua New Guinea from 1921 through 1923, then returned to the Antarctic on a second adventure with Douglas Mawson in 1929. He rejoined Australian forces as a photographer during the Second World War.

Hurley made several documentaries throughout his career. He also wrote and directed dramatic feature films and worked as cinematographer.

He died in January 1962, at age 76.

Advertisement