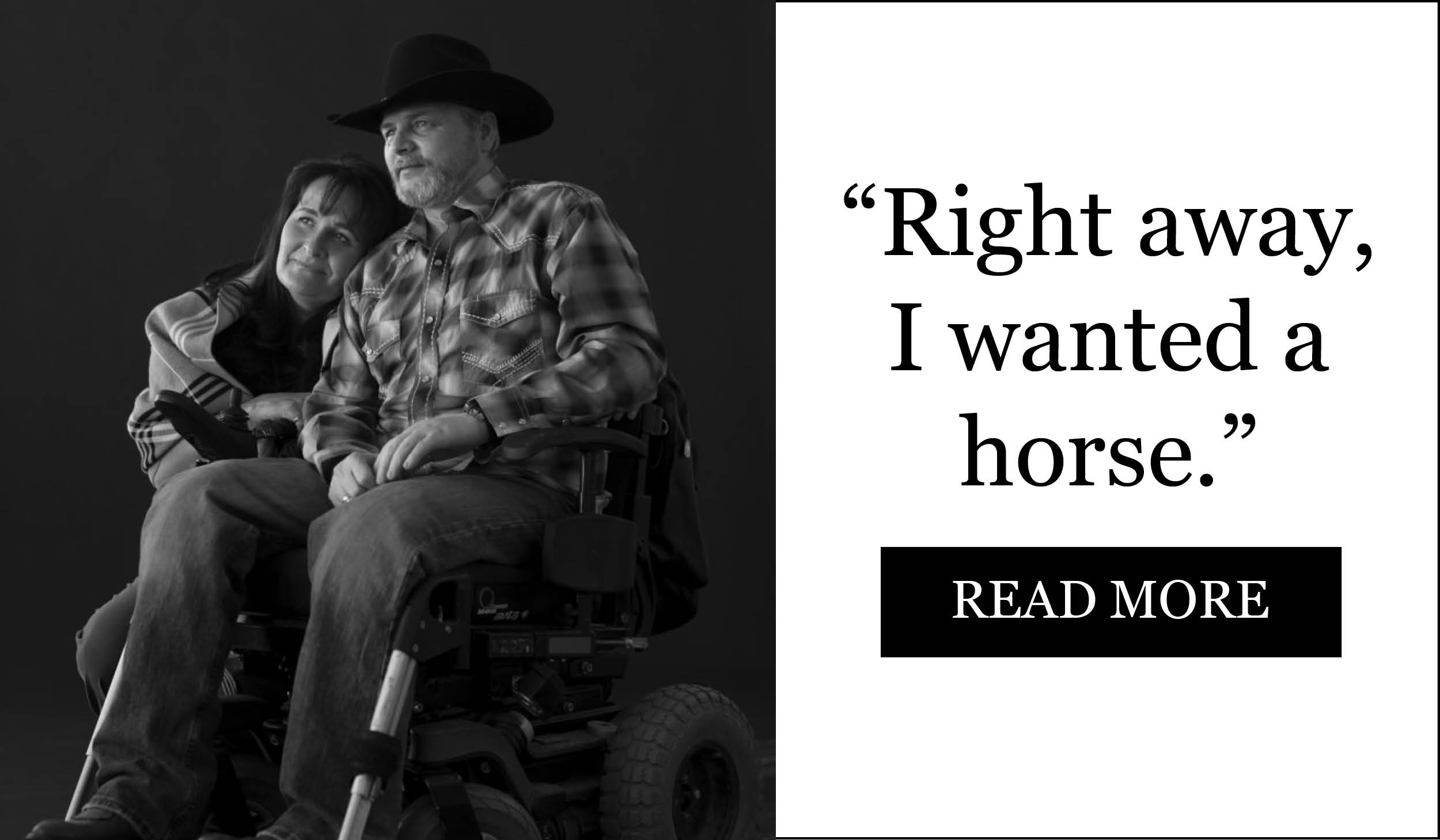

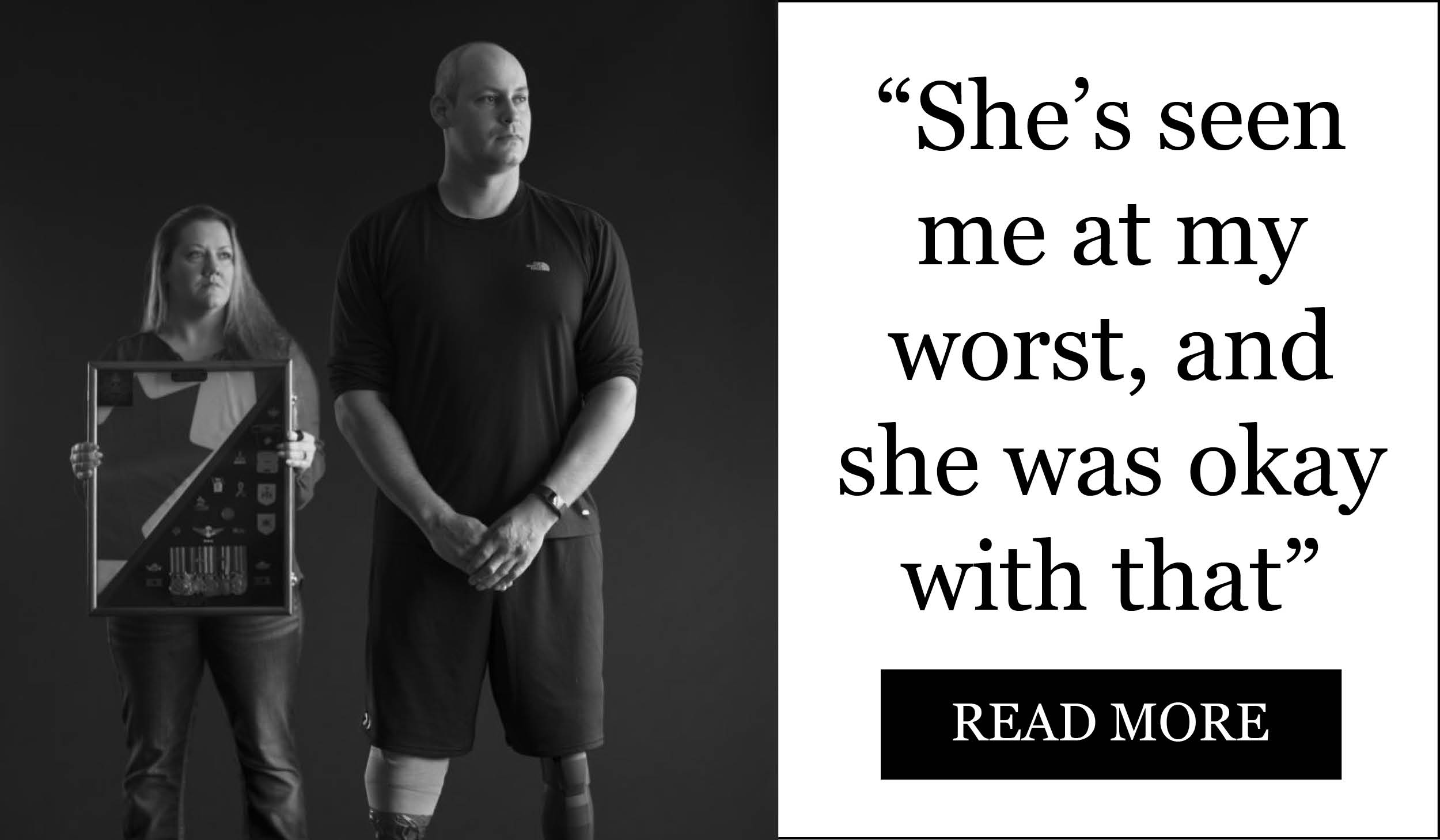

Veteran Andrew Knisley and fiancée Erin Moore.

Essay and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

They have been the forgotten heroes of wars from time immemorial, all but invisible as they swim the seas and scale the mountains that their wounds, physical and psychological, have laid before them.

It’s the war dead who get the attention. And rightly so, the wounded will say. Most don’t seek sympathy or accolades in their sacrifice and struggles, triumphs and defeats. They emerge from the shadows to demand what is due, and recede again.

“With regard to my stories,” wrote one soldier, who politely declined to participate in this project, “I’d prefer to keep them in my head. It’s nothing against you or the public, but I would rather be the quiet professional and put the war behind me.”

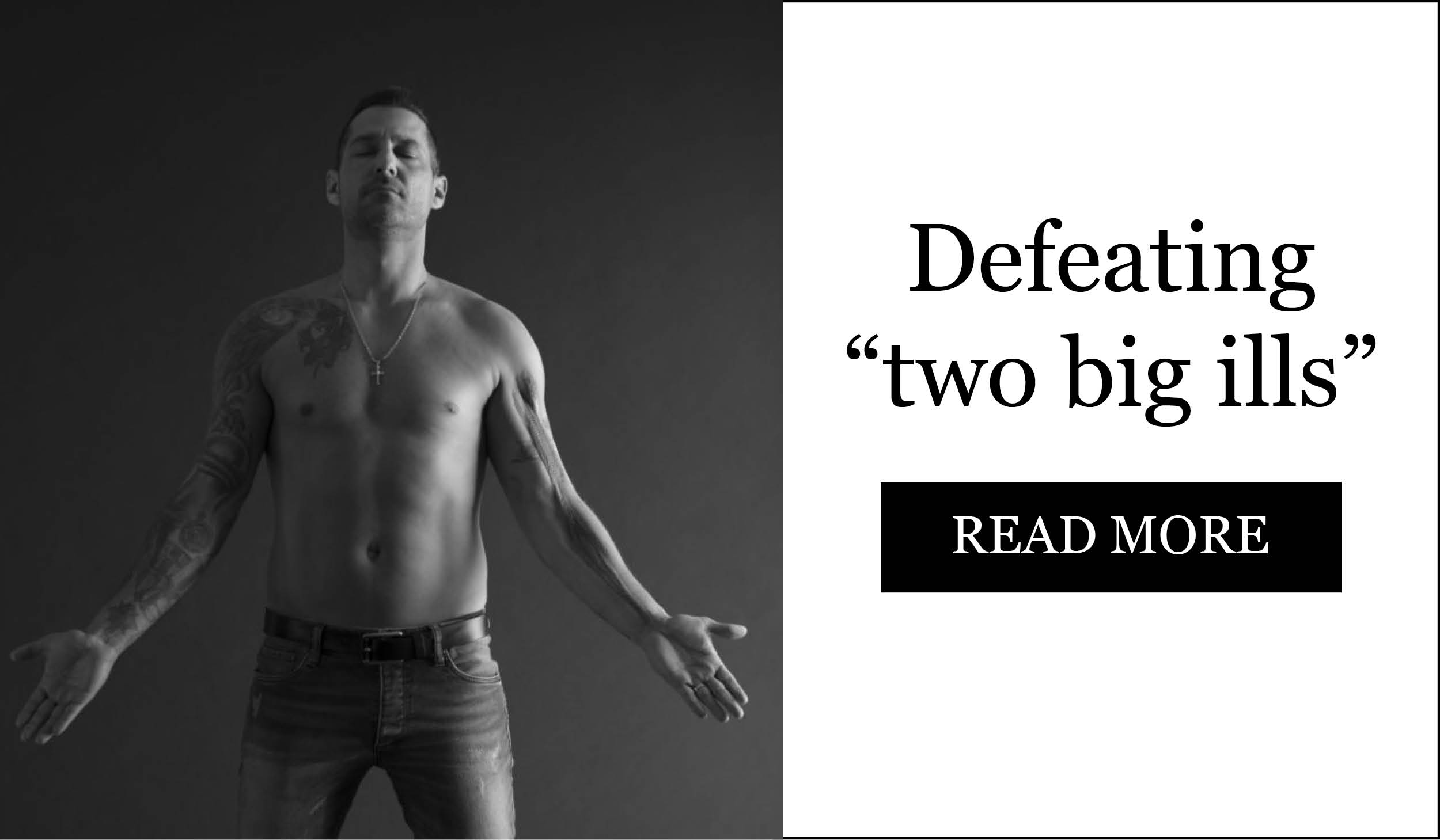

Many say they have changed, that their ordeals have transformed them in ways they could not have imagined, that only from reaching the summit of the highest peaks could they have viewed life with such perspective, only by plunging into the depths of blackness could they have seen the light.

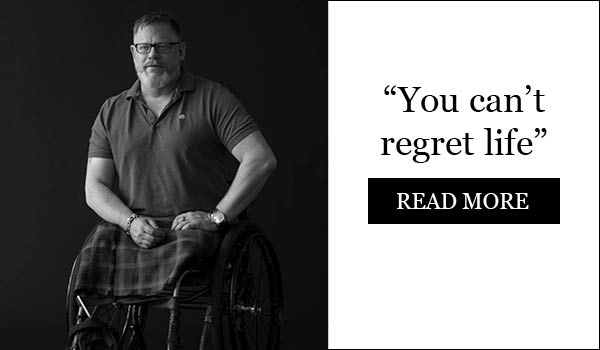

For those very reasons, perhaps, a surprising number say they wouldn’t have changed a thing.

“I’ve got no regrets,” said amputee Étienne Aubé, a field engineer from Drummondville, Que. “After coming through it, I appreciate life more than I did before. And at the end of my days, I’m going to say it wasn’t easy but I learned a lot and I earned a lot. I wouldn’t change anything. I’d do it again.”

They have trodden where few have gone, been sanctified by their own blood, faced down the beasts of unspeakable pain and suffering, and breathed the pure, thin air where there is no task, no priority, no distraction but survival itself.

They have known intimately the will to live. A few have even died, stepped into the abyss and returned, some more than once.

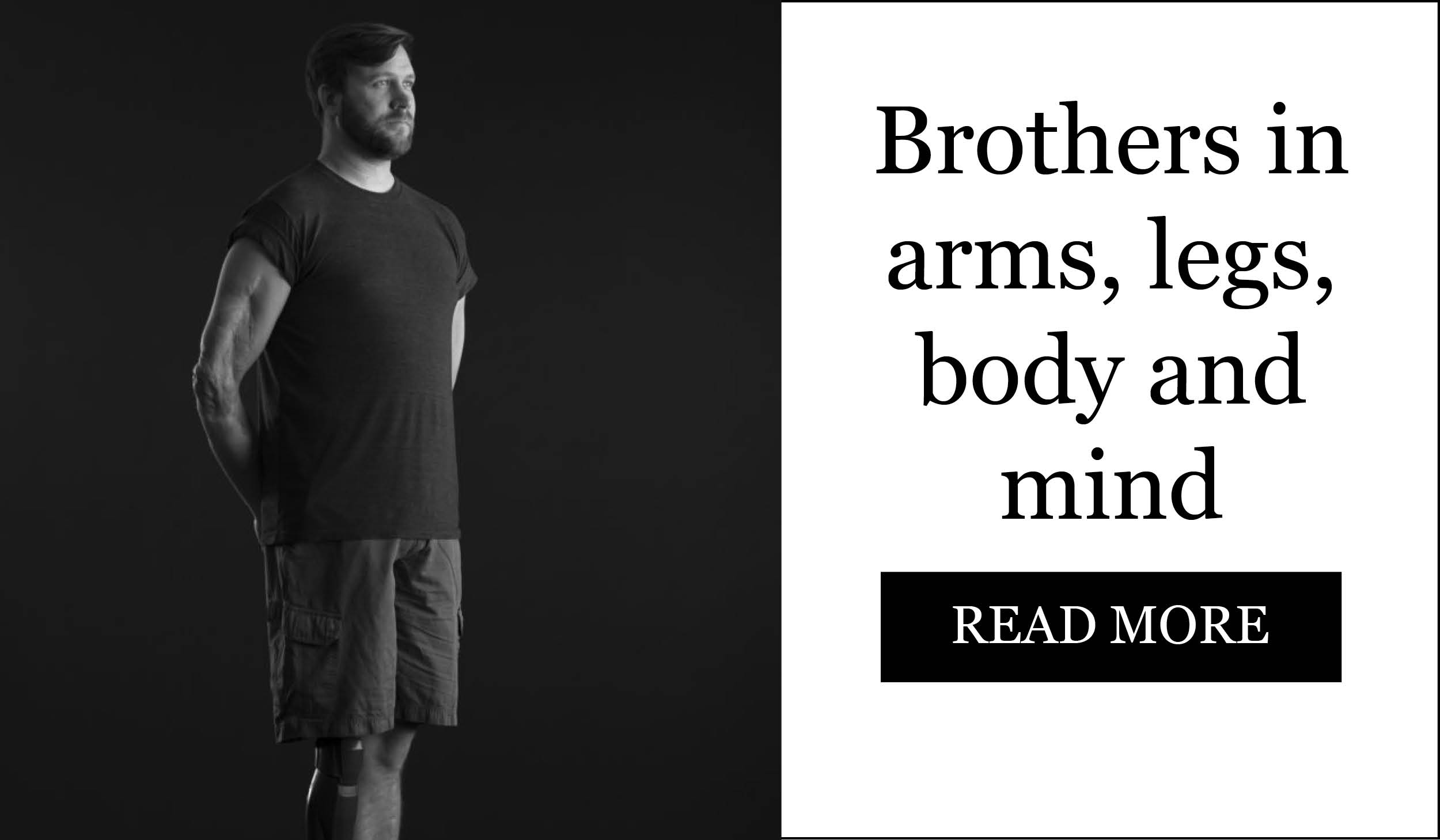

They belong to a society whose members are connected by a bond like no other, whose badges are never shed, whose rewards are life, belonging and little more. There is no thank you, no acknowledgement, no expression of sympathy that could possibly compare to the link they share.

Their sacrifices were made for a higher purpose. Most believe that. They must.

This brotherhood allows scant room for regret, doubt or self-pity. Its members learn to expect nothing and appreciate everything. They wear their badges with quiet pride. Their wounds are damnable blessings and exquisite burdens that will forever shape their lives.

Each in their own way is a miracle of modern medicine, a wonder of physical endurance and recovery, a testament to the indomitability of the human spirit.

Martin Renaud joined the Royal 22nd Regiment as a paratrooper at 17 and was wounded in Afghanistan at 19.

“I feel I’m blessed,” said Martin Renaud, who was a 19-year-old private in the Vandoos when he broke his back and lost both legs to a roadside bomb in Afghanistan more than 10 years ago. “I am a survivor. I fight for my life every day.

“I have friends fallen there.”

The costs are high. To never walk again. To negotiate an infinitely more complex life than one could ever imagine possible. To battle demons and darkness, year after year after year. To learn who your friends really are, and aren’t.

To reach the bottom and make the agonizing climb back up.

It takes years to rebuild a life. Years and years and years.

The shock, turmoil, setbacks and challenges have ripped relationships apart and forged others in steel. Tracy Kerr put her own mental health on the line to save the life of the man she loved, triple amputee Billy Kerr. Leah Cuffe considered no option but to stay with Mike Trauner after he lost both legs and nearly his left arm.

They have walked the hard ground together, laughed and cried, loved and fought. They have crossed to the other side of fear and come to know depth and richness in life, and love, that few have the privilege to share.

“I love you to pieces,” Leah would say. “Bring me some clean socks,” Mike would reply.

Along the way, Leah and Tracy took up the cause for others who did not have the support, encouraging them, helping them navigate a daunting bureaucracy through bad times and good.

Partnerships dissolved, too, some in the most callous manner possible. Cuffe recalled seeing a woman declare she would not be nursemaid to her newly disabled soldier and walk out, leaving him broken and alone in a hospital bed. She would never return.

A few did come back, and even married. If there’s one thing they know for certain, it’s that nothing is black and white.

For some, the road ended. They could see no way out from the darkness. They took their own lives and became casualties of war as much as those who returned in flag-draped coffins from the battlefields of Afghanistan and other far-off places.

So, next time you read or hear about Canadian soldiers killed and “injured” on the field of battle—and there will, inevitably, be a next time—honour the dead, but remember the wounded. They live on in the shadows.

To view more images and read other instalments in Stephen J. Thorne’s Portrait of Inspiration project for Legion Magazine, please click on the images below.

Advertisement