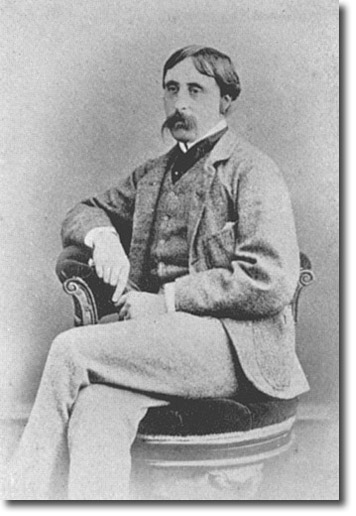

Alexander Roberts Dunn was the first Canadian to receive the Victoria Cross. [Wikimedia]

“Tensions were very high for not only the Eritrea[n] and Ethiopian armies,” he recalled of the UN mission to mediate a bloody border dispute between the neighbouring East African nations in the early 2000s, “but for us as well.”

In the Eritrean city of Senafe, Mitchell and a comrade were approached by children exclaiming “Canada” and tugging at their hands to follow them. “This thing smelled of an ambush badly,” he wrote, declining to be led to the unknown.

Two weeks went by, and the children persisted.

Ultimately, with considerable reluctance, Mitchell was ordered to investigate: “Now this is when it gets embarrassing for us. We geared up to follow these kids like we were entering an ambush…. We had over 300 rounds of ammunition per soldier, flak jackets, radios, machine guns…waiting for something to happen.”

Rather than assailants in windows and on balconies, the men were taken to a cemetery on the city’s outskirts. There, the children pointed to a single tombstone, weathered and beaten, but its name still readable: Alexander Roberts Dunn.

How, exactly, had Canada’s first Victoria Cross recipient—and one of the first-ever recipients of the award after it was instituted in 1856—come to end up in an all-but-forgotten graveyard in a country thousands of miles from his homeland?

And what had happened to him?

Alexander Roberts Dunn’s grave. [Findagrave]

“Dunn fended off the enemy blades,” recalled one witness, “drawing the full fury of their attention against him.”

Born in York (now Toronto) on Sept. 15, 1833, Dunn joined the British Army’s 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s Own) at age 19, later receiving a lieutenant’s commission before serving in the Crimean War against Imperial Russian forces.

The young Canadian officer, standing at 6’3″ with his blonde hair and large, walrus-like moustache, was an unceasingly striking figure, especially when mounted on his horse where he showcased a natural equestrian flair, skilled with a custom 1.2-metre (four foot) sabre, dashing derring-do.

Such qualities were put to the test on Oct. 25, 1854—170 years ago this week—amid the Battle of Balaklava. It was here that Dunn found himself in the infamous Valley of Death. It was here that Dunn joined the Charge of the Light Brigade.

The Russians, intent on relieving pressure on the Siege of Sevastopol while disrupting allied supply lines, advanced with 25,000 infantry, 34 cavalry squadrons and 78 artillery pieces under the command of General Pavel Liprandi. Having overrun Ottoman positions on a low ridge dubbed the Causeway Heights, the formidable enemy force captured the Turkish guns and pushed forward.

A temporary shift of fortunes came when the British 93rd Highlight Regiment repulsed an assault in what would be called the Thin Red Line, a since-renowned feat of arms against all odds. The 800-strong charge of the Heavy Brigade followed in due course, putting the Russians momentarily on the back foot.

It didn’t last for long. British Field Marshal FitzRoy Somerset, a 65-year-old commander who hadn’t seen action since Waterloo 40 years earlier, feared the enemy were removing the seized artillery pieces from the Causeway Heights.

Somerset handed ambiguous orders to his aide-de-camp, Canadian Captain Lewis Nolan, stating that any attempts to carry away these guns must be prevented. Alas, on the North Valley floor, the Cavalry Division’s Lieutenant-General George Bingham couldn’t see such movement beyond his field of vision. What he did see, however, were 12 Russian guns, protected by enemy cavalry, ahead of him.

When Bingham queried the orders, an impatient Nolan pointed vaguely at those same enemy positions: “There, my Lord!” he allegedly, and mistakenly, relayed.

And so, the fateful decision was made, perhaps most famously immortalized in Alfred Tennyson’s poem entitled The Charge of the Light Brigade:

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismay’d?

Not tho’ the soldier knew

Some one had blunder’d.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die.

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

After seven minutes of charging into the point-blank barrage, cut to ribbons with every stride, surviving members of the 11th Hussars, along with other battered remnants of the Light Brigade, tore into the Russians as best as they could.

Initially, the British horsemen appeared to have the upper hand until the lack of allied infantry support made a retreat inevitable. Dunn was well placed to return to relative safety when he spotted a comrade, Sergeant William Bentley, being attacked by three Russian lancers. The Canadian turned and dug in his spurs.

“Dunn fended off the enemy blades,” recalled one witness, “drawing the full fury of their attention against him, allowing time for Bentley to get to his feet.”

Having saved his comrade, the 21-year-old cavalryman repeated the feat with imperilled Private Harvey Levett. Dunn again dispatched the Russian assailants with his sabre, although Levett was nevertheless killed a few minutes later.

Figures differ wildly depending on the source, but some state that the Light Brigade lost 156 men killed or missing, 134 wounded, and at least 14 taken prisoner—as well as between 300 to 500 horses left dead on the battlefield.

It was a horrendous loss, but Dunn had likewise displayed extraordinary character.

Unfortunately, in doing so, his rifle slipped and discharged into his chest.

On June 26, 1857, Queen Victoria herself presented the then-24-year-old Canadian and 61 other veterans with the Victoria Cross at the first-ever grand investiture. The accolade was well deserved for Dunn’s actions in the heat of battle, even if his reputation had been tarnished by running away with his commander’s wife.

Dunn had previously left, but soon returned to the army as a major in the 100th (Prince of Wales’s Royal Canadian) Regiment of Foot. He eventually became the youngest British Army colonel and the first Canadian to command a regiment.

Fate, however, was not finished with Dunn.

Transferring to the 33rd (The Duke of Wellington’s) Regiment of Foot, the still-young and ever-adventurous officer participated in the British Expedition to Abyssinia—recognized as the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

There, Dunn met his surprising and unusual death.

The military coroner’s report seems befitting of the soldier’s insatiable character: While on a hunting trip, Dunn paused on a rock to uncork his brandy flask. Unfortunately, in doing so, his rifle slipped and discharged into his chest.

It’s far from the only theory, though. Among the speculative stories is that an old mistress, written out of his will, hired his valet to assassinate him. Another places the blame on a jealous husband exacting revenge. Suicide has also been floated as the cause, perhaps from survivor’s guilt following the Charge of the Light Brigade.

Regardless, Dunn had come to rest in Senafe. At the end of the Second World War, a British soldier noted the tombstone, and was surprised to find it had been cared for by Italian troops despite them formerly being on opposing sides.

But the site was forgotten again—that is until a UN peacekeeping mission happened upon it. This time, Colonel Dunn would be remembered.

“These [Eritrean] kids whom we thought were leading us into an ambush had done Canada a great service,” remarked Ben Mitchell. “This man was a legend.”

Advertisement