Eighty-one years on, a child frolics in the shadows of the Mulberry harbours deposited along Gold Beach at Arromanches, France, after June 6, 1944. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Eighty-one years after Allied forces hit the beaches of Normandy and launched the campaign to liberate Europe from six years of Nazi tyranny, the history still lives.

The bunkers and fortifications that formed Hitler’s Atlantikwall still cast a weary yet ominous presence over the English Channel. The wind, rain and threatening skies that clouded the beaches on June 6, 1944, still rage. The walls of courtyards, houses and 1,000-year-old churches still bear the scars of WW II battles.

And, of course, the cemeteries are sobering testament to the cost: more than 5,000 Canadians were killed from D-Day through the Normandy Campaign.

The history is not all visual, either.

At Château d’Audrieu, commandeered as a headquarters by Kurt Meyer’s 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitlerjugend), 24 Canadians, mostly Royal Winnipeg Rifles, were executed between June 8 and 11, 1944. They were among at least 156 Canadian prisoners of war murdered by Meyer’s troops in violation of international law in the days after D-Day.

David Scandrett, a former armoured trooper and commanding officer of the 3rd Canadian Ranger Patrol Group, listens intently to an account of the executions of three Canadian soldiers at the spot where they died in a Normandy forest. At least 156 Canadian soldiers were executed by Panzer SS troops after D-Day. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

It was the crunch, crunch, crunch of footsteps along the gravel pathway leading into the woods behind Château d’Audrieu, still hauntingly vivid, that first drew the attention of the owner’s daughter around 2 p.m. on June 8, 1944. She looked out the window and watched as the first three victims were escorted into the woods.

Today, walking into those woods along the same path where Major Frederick Hodge, commander of ‘A’ Company, Royal Winnipeg Rifles; his lance corporal, Austin Fuller; and Private Frederick Smith of The Queen’s Own Rifles made their last trek, the sound of those footsteps takes on an ominous tone. All three were summarily shot.

For historian and guide John Goheen, keeping this history alive has been a lifelong passion. For the past 30 years, the former school teacher has conducted tours to world war battlefields, cemeteries and museums throughout France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Historian and guide John Goheen, who has dedicated 30 years of his life to educating people in Canada’s military history, stands before a grave in Normandy. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

He has guided Royal Canadian Legion pilgrims to sites big and small—to grand monuments at places such as Vimy Ridge and Beaumont-Hamel, along the now-placid beaches that were once a hailstorm of lead and fire, and into hayfields and villages where Canadian units fought desperate battles with a determined enemy.

Here are some of those sites.

A man is seen through a gunport wading in the surf at Arromanches, France, 81 years after the D-Day invasion liberated the Normandy town from Nazi occupation. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

This Banksy-style mural in Arromanches, France, was actually done by a local brasserie owner, Vincent Brillant, and his artist friend Guillaume Debout (aka Hum Bub Hub). The work shows Brillant’s two young girls, ages four and eight, making a plea for peace. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

A German bunker lies dormant above Gold Beach 81 years after the D-Day invasion. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Not a German bunker, but a hay pile battling with the Normandy clouds in its quest to dry. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

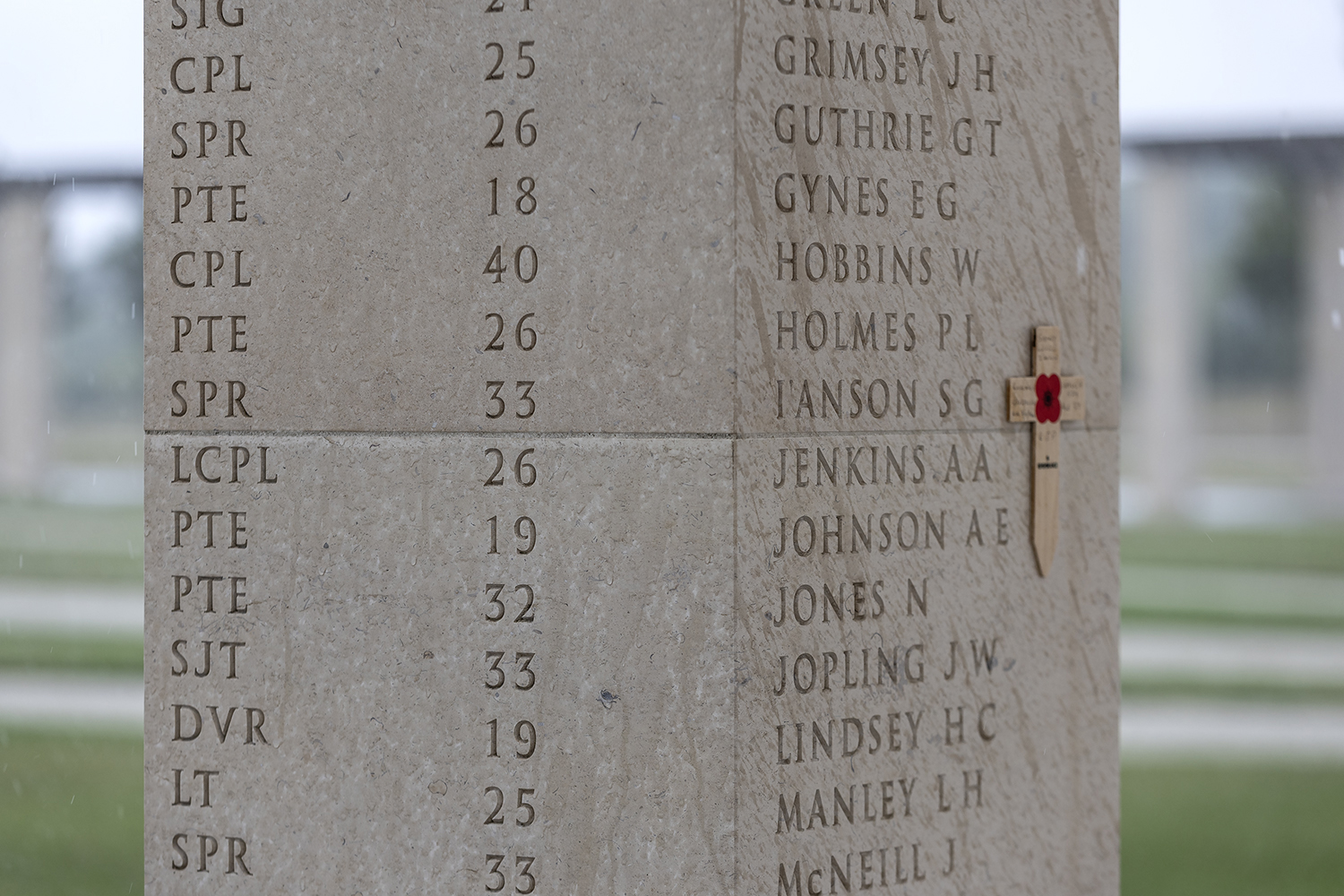

The young and the old are commemorated on the extensive British memorial near Gold Beach. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Cross of Lorraine monument on Juno Beach commemorates General Charles de Gaulle’s return to France after years of exile during WW II. He landed between Graye-sur-Mer and Courseulles-sur-Mer, on June 14, 1944, eight days after D-Day. The 18-metre tall stainless steel structure, was erected at the boundary between the two towns. The Cross of Lorraine became a symbol of national independence and symbol of rallying in both victory and defeat. The Free French Forces adopted it in July 1940 in answer to the Nazi swastika. It was later taken on throughout Free France and appeared on many insignia and monuments. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

A modest monument to the forces that freed Europe from Nazi tyranny stands at the gateway to Juno Beach near Courseulles-sur-Mer, France. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

A German gun still points at what was the beachhead at St.-Aubin-sur-Mer in June 1944. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Canadian Maple Leaf flags fly alongside the French Tricolore at Courseulles-sur-Mer—and throughout Normandy. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Lia Taha Cheng, director of poppy and remembrance at The Royal Canadian Legion national headquarters, completes her quest for the perfect poppy picture in Normandy. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Legion pilgrims walk the last path taken by three Canadian soldiers executed in the woods behind the Château d’Audrieu. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Historian and pilgrimage guide John Goheen leads a tour up the path where Nazi SS guards took three Canadians to be executed in the forest behind Château d’Audrieu. They were Major Frederick Hodge, commander of ‘A’ Company, Royal Winnipeg Rifles; his lance corporal, Austin Fuller; and Private Frederick Smith of The Queen’s Own Rifles. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Henry d’Eon, who served 28 years as a combat engineer in the Canadian Forces, sets foot in the courtyard at Abbaye d’Ardenne where 16 Canadian soldiers were executed by Kurt Meyer’s 12th SS Panzer troops. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Historian and guide John Goheen briefs pilgrims on the executions of 16 Canadian soldiers at the Abbaye d’Ardenne. They were marched across this courtyard, one-by-one, into the adjacent Abbaye garden, where they were shot. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Canadian special operations veteran Caleb MacDonald places a wreath at a memorial in the garden where 16 Canadian soldiers were executed by Nazi SS troops. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Armoured veteran David Scandrett pays his respects in a Normandy cemetery full of Canadians. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Greg Van Tighem, a highly decorated former firefighter from Jasper, Alta., walks the Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Canadian army veteran Roger Pineault of Saguenay, Que., wields a Maple Leaf Flag among the graves of Canadian servicemen killed during the Normandy Campaign. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

A building in Cintheaux, France, near the spot where German tank ace Michael Wittman was killed, still bears the scars of the fighting in Normandy 81 years ago. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

WW II battle damage to Église Saint-Gervais-Saint-Protais de Falaise. The cathedral’s construction is believed to have begun shortly after the conquest of England in 1066 under orders from William the Conqueror, a native of Falaise. It was completed during the reign of Henry I Beauclerc (1100-1135). Parts of the building date from the 13th, 15th and 16th centuries with renovations in the 18th century. Allied aircraft began bombing German-occupied Falaise on June 7, 1944. Canadian troops took the city in August. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Leopold Canal, where Canadian troops launched the Battle of the Scheldt from Belgium. German troops were defending the canal on just the other side; a bunker is still there, mid-left. The Dutch border is just a few hundred metres away. Securing the Scheldt River estuary was critical to exploiting the recently captured port of Antwerp, which would supply Allied forces as they pressed through the Netherlands and into Germany. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Pilgrims raise the flag at a small memorial near the Leopold Canal in the Netherlands. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Padre Robert Sicard stands over the graves of Canadian soldiers at Belgium’s Adagem Canadian War Cemetery. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Advertisement