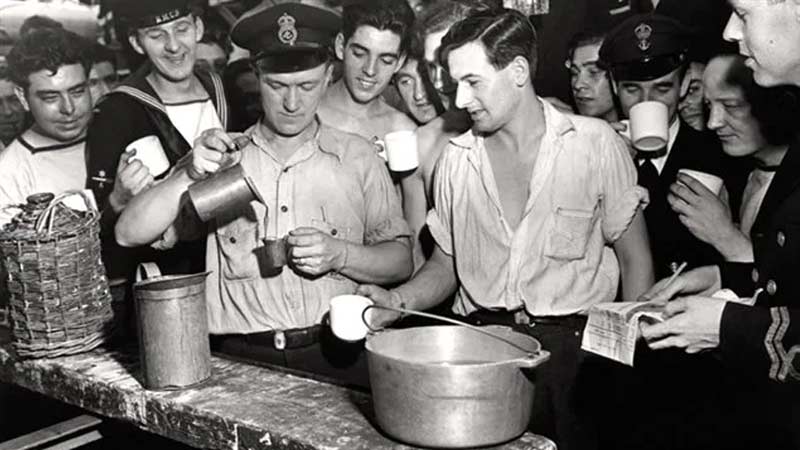

A sailor on board HMS York measures out tots of rum for the ship’s company, in preparation for the Royal Navy tradition “Splice the Mainbrace.”[Wikipedia]

The iconic tune, which first appeared in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island, could surprisingly be more fact than fiction in the Royal Canadian Navy.

Before Canada’s navy was established in 1910, Britain’s Royal Navy set the trends for much of life at sea.

Prior to the mid-17th century, the RN was still trying to figure out the best way to keep sailors hydrated. Water stored in barrels was an option, but due to the lengthy nature of naval travel, it would either run out or turn go bad before landfall.

Just because rum was the drink of choice didn’t make it the perfect beverage.

Beer was a better alternative, but it would still spoil on long trips, especially when travelling through the tropics.

But in 1655, after Britain invaded the then Spanish-controlled island of Jamaica, sailors found themselves confronted with a new, easily accessible choice of drink: rum.

Unlike beer and wine, rum’s high alcohol content ensured that it wouldn’t easily go bad. And since the daily ration was comparatively small—eight ounces to a beer’s gallon or wine’s pint—rum took up much less space.

But just because it was the drink of choice didn’t make rum the perfect beverage, with navy superiors often finding drunkenness and discipline didn’t go together with their subordinates.

So, in 1740, in an attempt to tame inebriated sailors, British Admiral Edward Vernon, who was referred to as “Old Grog” because of his “grogham” clothing, watered down the rum. The rum, now one-part liquor and four-parts water, was divided into two servings a day. The new recipe, which left many sailors grumbling, affectionately became known as “grog.”

Rum is distributed on board the corvette HMCS Arvida, September 1943. Arvida served as an Atlantic convoy escort and survived the war to be paid off in June 1945. [© John Daniel Mahoney, Library and Archives Canada—PA142439]

But by 1824, as the wars against France ended, rum became the Royal Navy’s official drink.

Every day at six bells, navy men could look forward to the ration out of the large oaken rum tub, that read its brass tributes to the king or queen of that time, while the bugle player horned out the “Rum Call.”

The act of rum rationing soon became referred to as “Splice the Main Brace,” which originated from when navy men would receive twice their daily rum rations for arduously repairing that part of the ship.

Scurvy was a tangible fear for many sailors back then, so grog’s style of serving was perfect for substituting water with lime juice.

“The daily rum tot was an important part of social life on the lower deck,” noted the Royal Canadian Logistics Association.

Not only was rum used to reward men for the drudgery of additional manual labour, boosting morale with a “sipper” (small sip), “gulper” (shot) or “sandy bottom” (the remaining rum in another shipmate’s glass), it also worked as a type of medicine.

Scurvy was a tangible fear for many sailors back then, so grog’s style of serving was perfect for substituting water with lime juice, thereby ensuring vitamin deficiency wouldn’t seep onto ships.

Rum also became a matter of currency between navy men, as well. While bartering booze was officially forbidden between shipmates, rum was still traded in exchange for standing watch, doing laundry, lending trousers and jumpers, as well as paying off bets. Some men would even hoard rations in their rooms for later use or opted for cash payments instead of rum. In 1945, about 60 per cent of Canadian seamen preferred the extra five-cents-per-day over a good tot.

Ordinary Seaman Ernest Weir receives an extra rum ration during Victory over Japan celebrations aboard HMCS Prince Robert, Sydney, Australia, Aug. 16, 1945. [© PO Jack Hawes / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-166428]

But as time went on, ambivalence toward the classic rum tot continued to rise as machinery seamen had to operate became more advanced.

“There was lots more sophisticated systems and perhaps less of the really hard manual graft,” former Royal Navy commodore Alistair Halliday told Forces.net.

And by the late 1960s, leaders of the Royal Navy felt like the tradition had overstayed its welcome.

“It seems it was a dark day for the Navy.”

On Dec. 17, 1969, the British Admiralty Board issued a statement concluding “that the rum issue is no longer compatible with the high standards of efficiency required now that the individual’s tasks in ships are concerned with complex, and often delicate, machinery and systems on the correct functioning of which people’s lives may depend.”

By the following summer, the RN’s daily rum tot had ended with a dark ceremony in tow, effectively known as “Black Tot Day.”

“It seems it was a dark day for the Navy,” said Halliday. “They had a display that was a gun carriage with a rum barrel on it.”

“It was like a funeral.”

Almost two years later, the Royal Canadian Navy followed suit in similar pomp and circumstance, having its own Black Tot Day on March 30, 1972, ending a tradition which cost the government $363,000 a year.

Despite this, Canada’s navy still allowed seamen to consume alcohol as long as they weren’t on duty within less than six hours. It was only in the last decade that the government hurled a partial ban on drinking any form of alcohol on naval vessels with the exception of special occasions.

Advertisement