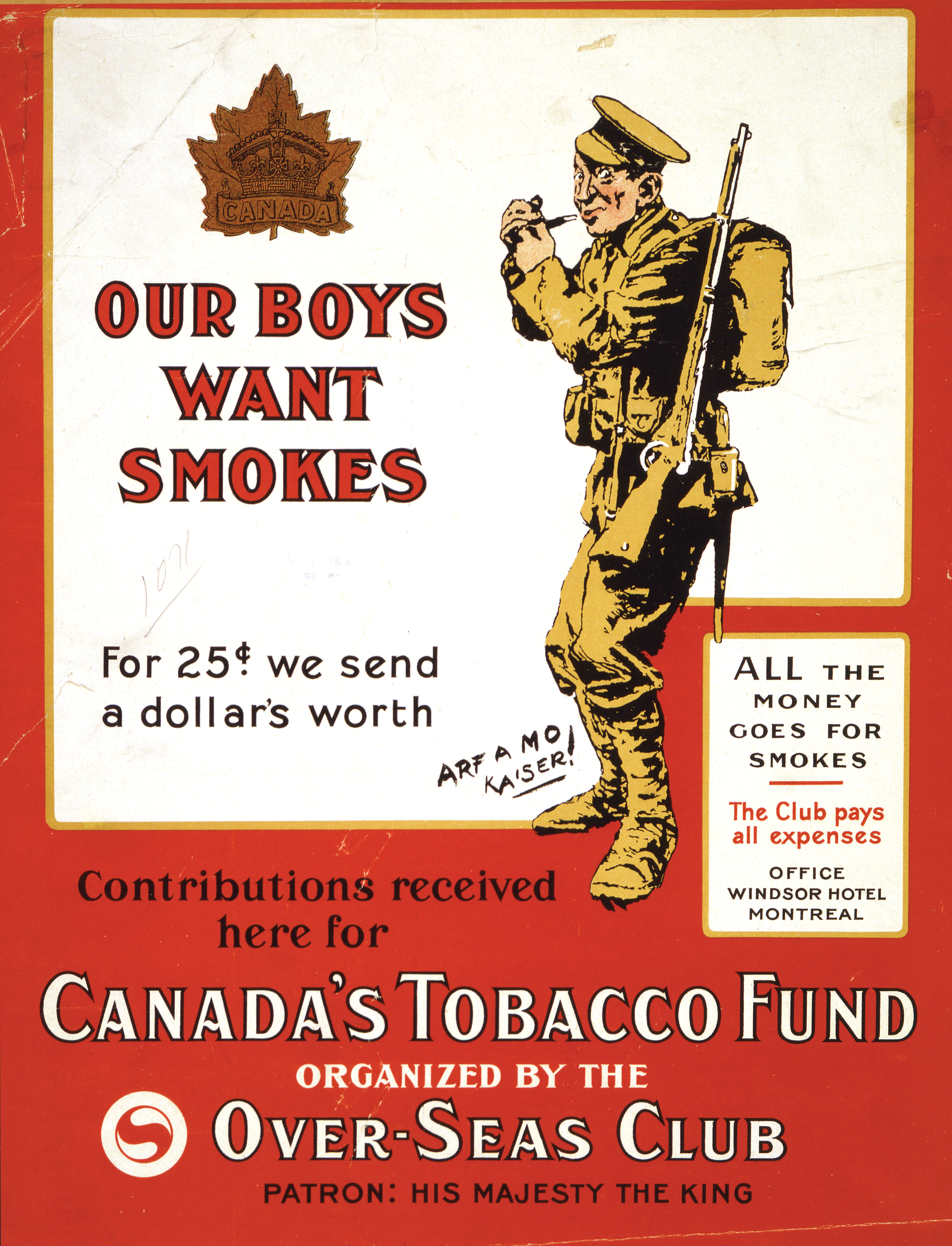

“Our Boys Want Smokes,” trumpets a First World War storefront window poster sponsored by the Over-Seas Club. “For 25 cents we send a dollar’s worth. Contributions received here for Canada’s Tobacco Fund.”

It was happening all across the country: show your patriotism and support our troops in the trenches overseas with gifts of tobacco. Even school kids in Brantford, Ont., were encouraged to donate their pennies to the local Children’s Cigarette Fund.

Many other groups in Canada enthusiastically supported similar campaigns. The Vancouver Kiwanis Club donated through an organization called the British Columbia Overseas Tobacco Fund. The Overseas League (Canada) Tobacco and Hamper Fund of Toronto was another. Employers, workers and relatives joined the fervour, sending cigarettes to overseas soldiers and sailors who often sent back postcards thanking the donors.

Predictably, tobacco manufacturers were major contributors to the funds and newspapers thanked them by regularly publishing lists of donors. Buttressing the patriotic angle, the tobacco industry also promoted and contributed large sums to the Victory Loans program—Imperial Tobacco gave $1 million, for example. Adding further to their patriotic image, they promoted military brand names. Cigarette manufacturer Tuckett Tobacco pushed its Army Navy brand and Imperial its Player’s Navy Cut.

Two leading Montreal newspapers championed the appeals early in the war. In November 1914, La Presse launched its tobacco charity with a stirring editorial for the Allied cause, emphasizing how necessary tobacco was in a war to defend civilization. It said smoking was an act that established man’s superiority over animals, and that its benefits included helping soldiers retain their self-control, soothe their nerves, distract them from sadness, and enable them to face dangers. Thus, the editorial solicited the public to donate cigars, cigarettes, tobacco and pipes—they could conveniently drop them off at any location where tobacco was sold. Vendors were to offer donation boxes with a sign that read “A little tobacco please, for our poor soldiers.”

Donations were collected by newspaper staff and delivered to a shipper. The federal government waived export duties and the French government funded its transportation overseas. The program won popular support, with unions and even employees of a Catholic monastery offering up donations.

A medic lights a wounded soldier’s cigarette. [Legion Magazine archives/LM_000300]

The Montreal Gazette launched its fund in early 1915, appealing to the public to show its patriotism by donating to the Gazette Tobacco Fund, proclaiming, “Our boys are giving their lives; all they ask of us is something to smoke.” With nationalistic spirit, it noted that English newspapers were providing British troops with 70 to 100 cigarettes a week; couldn’t Canadians do the same for their soldiers? To streamline collection logistics, the Gazette Fund accepted only monetary donations; no donations in kind were taken.

Twenty-five cents bought a package of 50 cigarettes and four ounces of pipe tobacco with matches. A dollar covered the cost of a full package for an individual soldier. Each full package contained one briar pipe, one rubber-lined tobacco pouch, one tinder lighter, 50 cigarettes, four ounces of pipe tobacco, and a return postcard addressed to the donor. By the end of 1918 when it wound down, the fund had collected more than $193,000, which had bought 25 million cigarettes, over a million packages of tobacco and 6,674 pipes.

The fund was constantly promoted by the newspaper. Almost every day during the war, along with the latest news from the front, the Gazette published articles and advertisements for the program. Many of the ads drew the attention of readers and donors to the fact that their contributions were being used for specific units of the Canadian contingent, often those recruited in the Montreal area.

One benefit of the Gazette Tobacco Fund was that it fostered contact and links between Montreal soldiers and their families and friends by way of the return postcard. It was an opportunity for communications, albeit brief, with friends and loved ones, which grew especially important as the war dragged on. The Gazette frequently published excerpts from these letters as well as their delivery time, to promote the fund and to encourage donors not to be discouraged that donations had perhaps been lost in the mail.

Philip Morris & Co manufactured cigarettes especially for the 77th Battalion from Ottawa. (Right) Player’s Navy Cut cigarettes came in a convenient tin. [CWM/20090109-033; CWM/19740414-003]

For many soldiers, the link the fund created between the front and home became stronger when the fund began sending Canadian cigarette brands instead of the British brands originally contracted to a British manufacturer. After receiving complaints, the Gazette contracted Imperial Tobacco to produce Sweet Caporals and Old Chum tobacco for the fund. The change prompted one soldier to comment that the tobacco he and his friends had previously received had been labelled “made specially for the troops,” and this was seen as a mark of inferior tobacco by the Canadian soldiers. The current packages included tobacco that was “a pleasure such as we have been used to at home.”

It still did not suit everyone. Future governor general Georges Vanier, who was a volunteer in the Royal 22nd Regiment, reportedly wrote to his mother in 1916 asking to send his favourite brand, Rouge Quesnel, for Christmas as it was popular with his men.

Other publications offered support. The July 1915 issue of the Canadian Cigar and Tobacco Journal, for example, wrote, “The greatest compliment the weed ever received is through the present national crisis…. The war has proved beyond doubt the value of tobacco to the human race. There is no greater boost for cigarettes than the soldiers’ appeal for them and the manner in which the people at home are responding to that appeal.”

Things were little different south of the border. When the United States entered the war in 1917, Congress prohibited alcohol and prostitution near army bases but allowed the “lesser evil” of cigarette smoking. U.S. General John Pershing appealed to the War Department that cigarettes were “no less important than bullets.” Billions of cigarettes were shipped overseas as army rations.

Many charity organizations that had once opposed cigarettes, including the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the Salvation Army and the Red Cross, agreed to support their distribution to American and Canadian soldiers. The move was justified by some charity members as a source of comfort or as a way to steer soldiers away from greater vices.

One YMCA official, previously a supporter of the anti-smoking movement, wrote: “There are hundreds of thousands of men in the trenches who would go mad, or at least become so nervously inefficient as to be useless, if tobacco were denied them. Without it they would surely turn to worse things….The argument that tobacco may shorten the life five or 10 years, and that it dulls the brain in the meantime, seems a little out of place in a trench where men stand in frozen blood and water and wait for death.”

A medic lights a wounded soldier’s cigarette. [Library of Congress/LC-USZC4-12681]

Not all opposition groups abandoned their anti-smoking battles; some thought the patriotic appeal was totally misguided and not at all helpful for the troops. Notably, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in Canada argued that sending tobacco as a “patriotic” gift to soldiers exposed them to “gas poison hurled upon them from the enemy’s side and tobacco poison thrust upon them from the side of their mistaken friends—fusillades of poison, both alike deadly in their effects.”

Health professionals also continued to speak out, warning of the serious health impacts of smoking. Health promoter John Harvey Kellogg, the inventor of corn flakes, wrote in 1917 that “more American soldiers will be damaged by the cigarette than by German bullets.”

But opposition to tobacco for the troops was mostly drowned out against the popular views that it was unpatriotic to do so, seriously setting back pre-war movements that were fighting tobacco.

Anti-smoking efforts had already been well underway by the late 1800s, and lobbying against cigarettes had become active in the years leading up to the war. At the front and one of the most effective forces was the WCTU. An early victory of theirs came from intense lobbying that led to a complete smoking ban on Montreal’s tram cars in 1901. Moreover, teaching the dangers of tobacco and tobacco smoke formed an integral part of Canadian school curricula in the early 20th century.

Partly due to WCTU lobbying, parliament had introduced, debated and passed at second reading and report stage in 1904, Bill 128, An Act to prohibit the importation, manufacture or sale of cigarettes. But stiff opposition prevented a third reading and it was never adopted as law. A much watered-down bill, the Tobacco Restraint Act, was subsequently introduced and passed in 1908. It prohibited the sale of tobacco to minors and possession of tobacco by minors.

A wounded soldier still enjoys a cigarette in September 1916. [DND/LAC/PA-000626]

The WCTU wouldn’t let up. It continued its cigarette prohibition campaign and was eventually given attention by the Conservative government of Robert Borden, which appointed the House of Commons Select Committee on Cigarette Evils in 1914 to study the issue.

But it was a losing battle. By mid-1914, public and government priorities were focused on war, and although it conducted some public hearings, the committee ran out of time before hearing from cigarette manufacturers and the WCTU. That became a death knell for government involvement in the tobacco wars: parliament would not seriously debate tobacco control for another six decades.

With the threat of a cigarette ban now off the table, the Canadian tobacco industry jumped into the business of promoting and selling them. And by linking cigarettes to patriotism, the tobacco funds would just grease the skids for them. The impact was that cigarettes became part of soldier culture.

It clearly didn’t end with the 1918 Armistice. Most soldiers, who returned home as heroes, were smokers (more than 90 per cent by one 1917 survey), which gave smoking a ringing endorsement. So cigarettes boomed in popularity after the war, and manufacturers capitalized on the wartime momentum by stepping up advertising and promotion campaigns. Cigarettes and pipes came to be associated with sophistication, leisure and affluence; movies and magazine advertisements boosted their connotations of glamour and cool. Annual cigarette consumption in Canada skyrocketed—from 87 million in 1896 to 2.4 billion in the 1920s.

Tobacco historians generally agree that the First World War, more than any other factor, legitimized the cigarette and established its popularity for decades to come. And tobacco funds, however unintentionally, played a major role.

Top Photo: Cigarettes come out as soldiers relax in front of a dugout. (Library of Congress/LC-USZC4-12681)

Advertisement