Commissioned on Jan. 19, 1944, the submarine travelled to Norway to join the German 3rd flotilla in early August under command of Korvettenkapitän Wolf-Axel Schaefer.

Its first and only patrol began on Aug. 18. The sub passed through a gap separating Iceland and the Faroe Islands and headed for the Hebrides, where it was sunk on Sept. 9. All 52 aboard perished.

Who sank the sub? That depends on what you read and where and when it was written. An RCAF Sunderland flying boat piloted by J.N. Farren spotted whitish vapour or steam and a 30-metre wake indicating a submarine. It dropped eight depth charges, then called in HMCS Hespeler and HMCS Dunver, on patrol south of the Hebrides.

“The original postwar analysis credited the Sunderland’s attack with the probable sinking of U-484,” wrote Brereton Greenhous et al in The Crucible of War, the official history of the Royal Canadian Navy, in 1994. “In retrospect, it seems far more likely that the German submarine was sunk by HMCS Dunver and HMCS Hespeler.”

But a few years later, the credit was transferred to two British ships, HMS Portchester Castle and HMS Helmsdale. Those ships had originally been credited that same day with sinking U-743 northwest of Ireland, a U-boat reported missing on Sept. 10.

In 1997, Royal Navy historian R.N. Coppock reported he had found evidence suggesting the British ships had not sunk U-743, but U-484 instead. The historian went through Allied and Kriegsmarine records, adding four kills to the RCN tally, and transferring credit for the sinking of U-484 to the RN. U-743 was deemed lost from unknown causes.

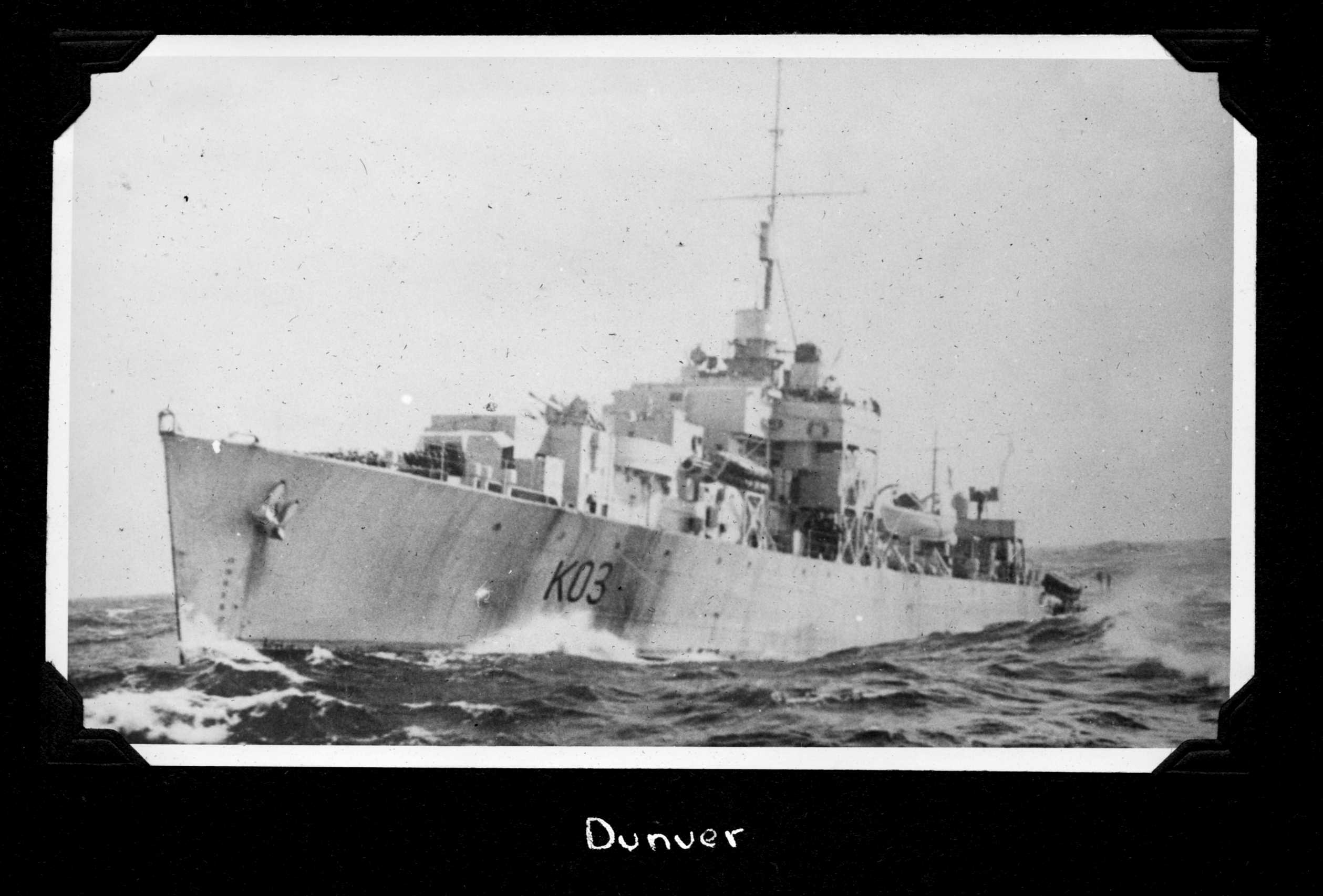

HMCS Dunver served as a convoy escort in the Battle of the Atlantic. The ship was named for the city of Verdun, Que. [James White/Flickr]

In 2008, purported unpublished diary entries of a Hespeler sailor posted on a SUBSIM Radio Room online forum seem to support the Canadian claim: “(9/9/44) we left at 0015 and two hours later picked up a contact and went to ‘action stat.’ We dropped one pattern and nothing happened. The second caused explosions. Nothing the third. Fourth caused explosions and the fifth brought something up which the Dunver said was a sub. We secured at 4:30 a.m…. (9/10/44) Tons of oil, wreckage, and bodies about.”

In a 2013 article in Starshell, the Naval Association of Canada magazine, retired navy commander Fraser McKee credits the Canadian ships with the sinking, noting the RN disputes the sinking “but without any better claim than the RCN’s.”

Many online sites credit the British ships with sinking U-484. The U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command has a question mark after its entry crediting the Canadian ships. The online RCN history site credits Hespeler and Dunver.

It would take strong new evidence to put an end to the disagreement.

Advertisement