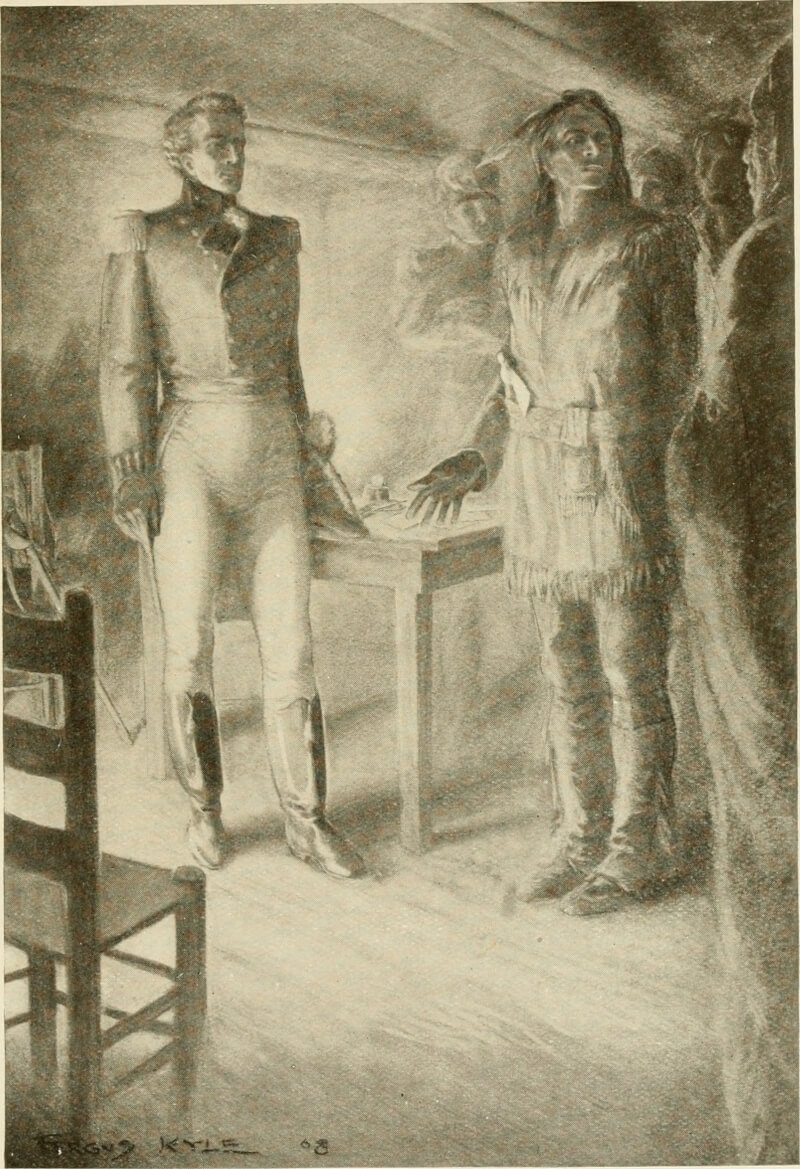

Major General Isaac Brock met with Shawnee chief Tecumseh in Amherstburg, Ont.

On Aug. 13, 1812, Major-General Isaac Brock arrived at Fort Malden. There, intent on reinforcing the garrison near Amherstburg in present-day Ontario, the British commander of Upper Canada was greeted by the sound of gunfire.

The din of musket shots came not from the American side of the Detroit River, where 59-year-old U.S. General William Hull was now on the defensive after a failed invasion of Canada launched a month earlier, but were the weapons of Indigenous allies led by Shawnee Chief Tecumseh.

Discharged into the air, it was meant to be a welcome.

Brock sought out his Indigenous counterpart for two reasons: Firstly, he wished for Tecumseh’s warriors to save their ammunition ahead of the imminent siege of Detroit; secondly, Brock hoped to meet the man who, harnessing ambitious vision and leadership, had created a confederacy of tribes and peoples.

Showing their profound respect for each other by wearing their finest attire, the unlikely duo—one, a 42-year-old career officer adorning a scarlet uniform; the other, a 44-year-old Ohio-born chief dressed in a tanned deerskin jacket and trousers with a silver medallion of George III—met at a candlelit table.

Neither was Canadian nor, indeed, had any great affinity for British North America. Nevertheless, as they began formulating a strategy, it became evident that both had a shared goal: to check an expansionist U.S.

Fate would do the rest.

The pair agreed that Fort Detroit—where General Hull had withdrawn to after a dithering and ill-conceived offensive campaign north of the border—could fall to a game of psychological warfare. Recognizing the enemy commander’s fear of Indigenous warriors, they planned to capitalize on his long-held trepidation.

The Surrender of Detroit. [J.C.H. Forster/Wikimedia]

Before charging into battle, the British major-general dispatched two officers under a flag of truce to deliver a message to Hull. Calling for Fort Detroit’s surrender, Brock’s words were clearly crafted to instil dread.

“It is far from my inclination to join in a war of extermination,” he noted, “but you must be aware, that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond my control the moment the contest commences.”

Yet Hull was not to be so easily swayed. In his response rejecting the offer, he wrote: “I am prepared to meet any force, which may be at your disposal.”

Amid an ensuing artillery barrage between the sides, Tecumseh and his men enacted their backup plan of a nighttime crossing of the Detroit River, landing three kilometres away to avoid detection. They awaited morning’s first light.

The next day, Aug. 16, Brock’s Anglo-Canadian force made its own crossing with the major-general leading from the front. On the other side, he learned that several hundred American soldiers were behind him en route to the fort.

Despite being wedged between two enemy forces, Brock pressed on. Finally, the plan he and Tecumseh had conjured could begin.

The commander, having kitted out his Canadian militiamen in British regular uniforms to further increase American anxieties, marched to within a kilometre and a half of the fort. Meanwhile, Tecumseh’s warriors crossed in front several times, sneaking back behind cover on each occasion to create the illusion of a larger force.

Both leaders soon found one another and climbed a hill to view the would-be battlefield. There was to be no such fight, however, as Brock and Tecumseh watched the gates of Fort Detroit open and a lone American rider depart.

The horseman galloped toward the two men; in his hand, he clutched a stick on which a white handkerchief fluttered. The almost-bloodless siege was over.

A humiliated General Hull later attempted to justify the surrender. Writing from captivity to U.S. Secretary of War William Eustis, he claimed—among other arguments—that after the previous American surrender at Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island), “almost every tribe and nation of Indians, excepting a part of the Miamies and Delawares, north from beyond Lake Superior, west from beyond the Mississippi, south from the Ohio and Wabash, and east from every part of Upper Canada, and from all the intermediate country, joined in open hostility, under the British standard, against the army I commanded.”

“Push on, brave York volunteers!” shouts Issac Brock, who is shown mortally wounded at the lower right of the picture. [John David Kyle/Wikimedia]

The two leaders could now bask in the glory of their ingenious tactics, prompting an exchange of gifts in a spontaneous gesture of goodwill. Brock offered a pair of pistols and the silk sash from his uniform. In response, Tecumseh presented the British major-general with a decorative scarf.

Alas, fate had decreed that they should never fight together again.

On Oct. 13, 1812, destiny caught up with Brock at the Battle of Queenston Heights, where he died leading British troops against American invaders.

A similar fate met Tecumseh about a year later—Oct. 5, 1813—during the Battle of Moraviantown on the Thames River in Upper Canada. His death resulted in the effective disintegration of the First Nations confederacy he had long cultivated. It also dealt the hopes of an Indigenous victory against the U.S. a devastating blow.

Still, both men died Canadian heroes, even if neither were Canadian by birth.

Advertisement