Sub-Lieutenant Hampton Gray following his graduation as a pilot at Kingston in September 1941. [wikimedia]

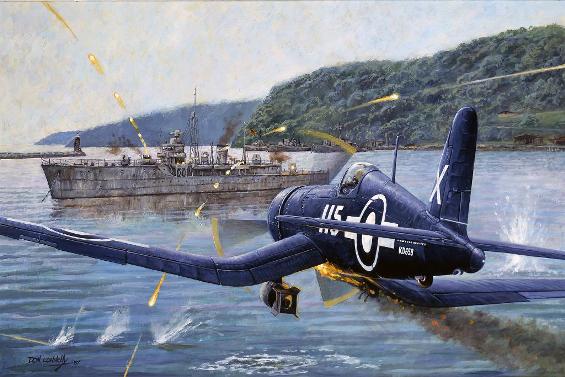

Gray’s flight of eight fighters had been on a sortie near Onagawa Bay, Miyagi Prefecture, when he spied a cluster of enemy naval vessels. Among them was the Etorofu-class destroyer escort Amakusa, two minesweepers, a training ship and submarine chasers. Gray targeted the 1,000-ton Amakusa.

Under a maelstrom of flak and tracer fire, he descended to within 12 metres (40 feet) of the waves and pressed home the attack.

Unfortunately, Gray’s deft manoeuvring couldn’t prevent one of the Japanese ship gunners or shore batteries from striking a hit against him. His aircraft shuddered as shrapnel tore away one of his two bombs, followed by flames gushing out of the fatally stricken plane. Gray nevertheless pushed on.

Once within range of Amakusa, he let loose his remaining payload.

The bomb penetrated amidships, triggering an explosion that caused the vessel to sink within minutes. Meanwhile, Gray—likely wounded—flew past the wreckage for an additional few seconds before his Corsair transformed into a fireball and crashed into the ocean. The B.C. airman was never seen again.

Lieutenant Gray would never know that his heroic exploits occurred on the same day that the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Nor would he ever learn of his earning the Victoria Cross, posthumous as it was, for sinking the Amakusa. He would also receive the dubious recognition of being one of the last Canadians killed in action during the Second World War.

Lieutenant Hampton Gray’s final moments by Don Connolly. [CWM 19880046-001]

At Brophy’s insistence, a still-alight Mynarski crawled back through the fire, saluted and jumped out.

Just over one year earlier—on the night of June 12-13, 1944—Royal Canadian Air Force airman Andrew Mynarski had joined his Lancaster bomber crew in a raid against rail yards in Cambrai, France. The 27-year-old mid-upper gunner, hailing from Winnipeg, encountered an enemy night fighter en route to the target.

The ensuing attack knocked out both port engines and caused the wing tank to catch fire. Another burst tore through the Lancaster’s fuselage, starting a second fire between Mynarski’s turret and tail-gunner Pat Brophy, a close friend.

With their bomber severely damaged, the crew were instructed to bail out. Brophy, however, was trapped in his turret after German fire destroyed the hydraulic system. Instead of saving himself, Mynarski attempted to free his fellow comrades by crawling through the blaze, which set him partly on fire, too.

Alas, following repeated and increasingly desperate attempts, it became evident to both parties that the turret would not budge. At Brophy’s insistence, a still-alight Mynarski crawled back through the fire, saluted and jumped out.

Fate would have it that Brophy survived. Miraculously, when the Lancaster crashed near the village of Gaudiempré, close to Amiens, the impact freed the jammed turret and flung the airman safely away from the wreckage.

Mynarski had no such luck. Though he was alive when he landed in northern France, he eventually died from his burn wounds.

Despite Lieutenant Gray being the last Canadian to perform actions that earned the Victoria Cross on Aug. 9, 1945, he was not the last to be awarded one. That honour, albeit equally tragic, fell to Pilot Officer Mynarski for his actions on June 12-13, 1944, whereby he was recognized with a posthumous VC on Oct. 11, 1946—about one year and two months after Gray’s ultimate sacrifice.

What remained—and remains—indisputable is that both Canadian VC recipients showcased extraordinary courage at a terrible cost.

Indisputable, too, is the identity of Canada’s last living Victoria Cross holder. Private Ernest (Smokey) Smith earned the Commonwealth’s highest military honour in Italy on Oct. 21-22, 1944. His death on Aug. 3, 2005, at age 91, closed a chapter on Canada’s Victoria Cross story so far.

Advertisement