She’s a big lumbering brute but, oh, how she flies!

Proponents of the Spitfire would no doubt take umbrage, but devotees of the bigger warbirds of the Second World War unabashedly call the Avro Lancaster the most beautiful aircraft ever built.

The crews who survived those long, cold and terrifying night missions over Germany—stragglers limping home, as they so often did, with their fuselages riddled by flak and 30mm cannon rounds, chunks of plane missing and wounded or dead aboard, hoping against hope they weren’t pursued—no doubt have a case.

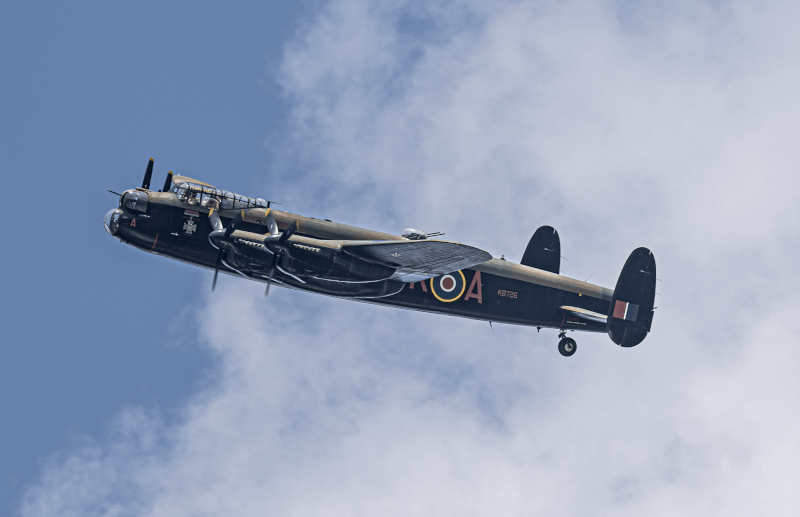

One of 430 Lancasters built at Victory Aircraft in Malton, Ont., the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum’s 78-year-old Mk. X is one of only two of the bombers flying today. The other is in Britain.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Four of the legendary Rolls-Royce Merlin engines took them to their targets and, by skill and good fortune, four—or fewer—brought them back.

By war’s end, Lancs had become one of the most heavily used night bombers of the Second World War, delivering 608,612 long tons (618,378,000 kg) of explosives over 156,000 sorties.

With Americans bombing by day, the air campaign proved brutal to both sides: More than half a million German citizens were killed by Allied bombs.

Of every 100 airmen who joined Britain’s Bomber Command, which included Canadians and other Empire airmen, 45 were killed, six were seriously wounded and eight became prisoners of war. Just 48 escaped unscathed.

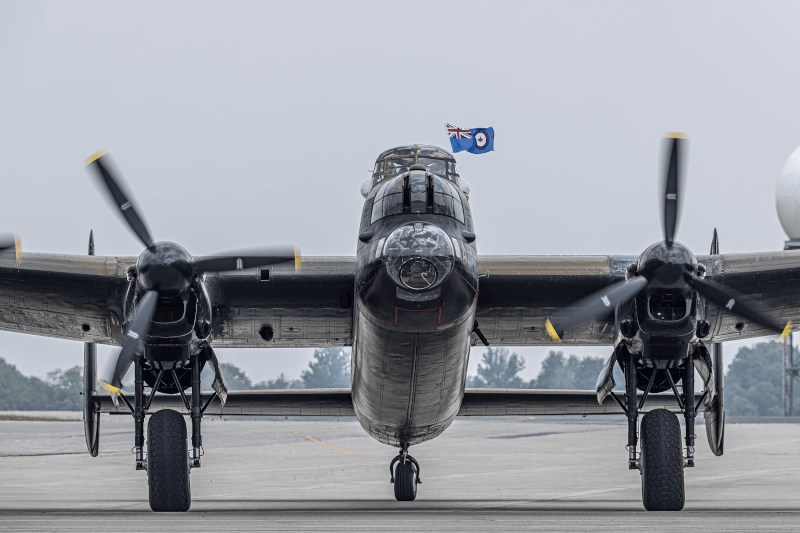

The Mynarski Lancaster of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum rolls out across the tarmac at Hamilton, Ont. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

By the time the war ended, 55,573 Bomber Command crewmen were dead, more than 10,000 of them Canadians.

But the legend of the Lancaster lived on. Only two still fly today, one of them in Canada.

The Lancaster was crewed by seven: pilot, flight engineer, navigator, wireless operator, bomb aimer (who also operated the nose guns), mid-upper gunner and, in probably the most unenviable role, the rear gunner. [Credit: Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

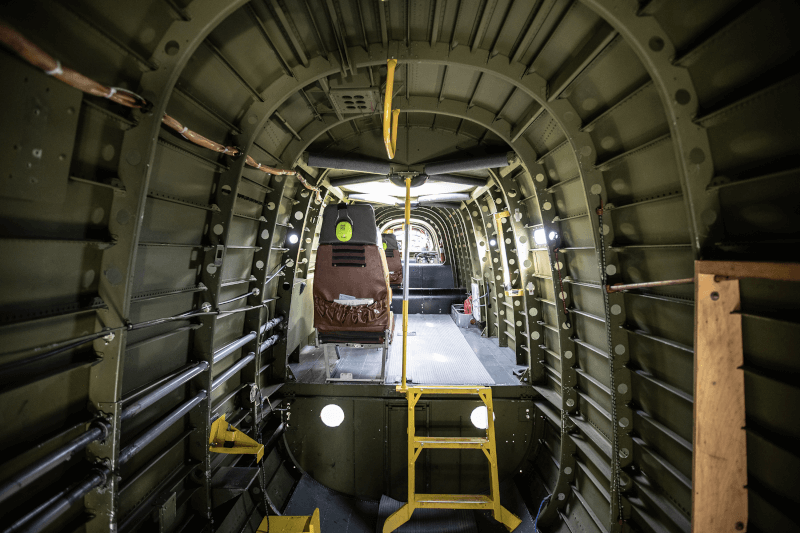

The Lancaster cockpit. There was only one pilot aboard the heavy bomber. The flight engineer, whose primary job was managing the engines, fulfilled the role of co-pilot.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

As in virtually all bombers, the Lancaster fuselage was rudimentary—functional, without luxuries of any kind. It consisted of five main sections, built separately, often at different locations, and transported to various sites for assembly. The metal was paper-thin, offering little to no protection. Forward crew had to climb over the main wing spar inside the fuselage to take up their positions in the aircraft. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The rear gunner occupied a cold, cramped and near-inaccessible turret in the very back of the fuselage. He operated four .303-calibre machine guns on a single trigger, their ammunition belts running the length of the aircraft. The turret had to be rotated and a hatch opened to get in and out. Of the 55,573 Bomber Command crew killed in WW II, some 22,000 were tail gunners, or almost 40 per cent of the KIAs in a crew of which they comprised 14 per cent. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Canada’s Lancaster, one of only two flying in the world today, bears the livery of the plane crewed by Canadian Pilot Officer Andrew Charles Mynarski, with one addition—a Victoria Cross alongside the pilot’s seat. Mynarski, a mid-upper gunner, earned a posthumous VC trying to save his burning plane’s tail gunner, Sergeant Pat Brophy, as their aircraft went down over France. “The Pilot Officer unhesitatingly moved back through the flames and tried to release the gunner, although his own clothing and parachute were on fire,” said Mynarski’s citation. “All his efforts to move the turret and free his comrade were in vain, and eventually the gunner told him to try to save his own life. Reluctantly P/O Mynarski moved to the escape hatch and there, as a last gesture, turned towards the trapped gunner, stood to attention in his flaming clothing, and saluted before jumping.” Incredibly, Brophy survived the crash. Mynarski survived the jump, only to die from his burns the following day. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Lancaster on run-up prior to take-off. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Sir Arthur Harris, commander-in-chief of Bomber Command, sang the praises of the Lancaster at war’s end, though his estimation of its impact may have been somewhat exaggerated. “I would say this to those who placed that shining sword in our hands: ‘Without your genius and efforts we could not have prevailed,’” he wrote in a letter to the head of Avro. “For I believe that the Lancaster was the greatest single factor in winning the war.” A total of 7,377 Lancasters were built between 1941 and early-1946. Some 3,500 were lost on operations, and another 200 or so were destroyed or written off in crashes.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Returning home, the RCAF pennant flying.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

It was May 19, 1942, and the BBC was recording its annual broadcast of nightingales singing in a 16th century English country garden in Surrey, south of London, when 197 bombers passed overheard en route to Mannheim, Germany—105 Wellingtons, 31 Stirlings, 29 Halifaxes, 15 Hampdens, 13 Lancasters and four Manchesters, their distant hum gradually becoming an ominous rumble behind the singing of the nightingale. Eleven of the aircraft did not return that night. The broadcast, which had been conducted in various forms each year for nearly two decades, was cancelled over operational security concerns.

Lancaster crew shoots down a Luftwaffe night fighter on final approach to their target in Berlin.

Advertisement