A century ago, Canadian medical officer John McCrae saw “every horror that war had,” including the death of a close friend, and penned a poem that inspired countless acts of remembrance

“A poet and a scientist and a soldier—a scholar, a gentleman, a Christian, a fine fellow, generous, unselfish. And over all this there was the charm, the esprit, the freshness of the bubbling personality of Jack McCrae.”

This tribute paid to Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae after his death in January 1918 highlights some of the many facets of the man whose famous poem, “In Flanders Fields,” was written a century ago. With the centenary of the Second Battle of Ypres, during which it was composed, comes the opportunity to honour McCrae and his life, work and legacy.

McCrae was born in 1872 in Guelph, Ont., the second son of parents who had immigrated to Canada from Scotland. Hard work, duty, service to others, and a strong religious faith were McCrae family values. Young John—Jack to family and friends—proved to be a gifted student whose wide-ranging interests included botany, animals, music and a love of writing, literature and poetry that was encouraged by his mother. Despite suffering from asthma, he participated in sports and enjoyed outdoor pursuits throughout his life. His keen interest in military matters, inspired and encouraged by a father who was active in the local militia, won McCrae a prize as the best-drilled cadet in Ontario. He later passed a militia artillery officer’s training course at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont.

McCrae lived in a period when Canada was a still young country and a member of the family of nations of the British Empire. Great Britain was a leading world power, but signs of her decline were beginning to surface as other countries, such as Germany, sought influence on the international stage. By 1899, when war broke out in South Africa between the British and the Boers (Dutch and Huguenots who settled in southern Africa in the late 17th century), McCrae had completed medical studies and started post-graduate work. He set it all aside to volunteer for the militia artillery component of the second contingent of troops that Canada sent to assist Britain. When he returned from South Africa in 1901, he had seen action and experienced the dangers and hardships of armed conflict.

![McCrae saw active military service in the Boer War as an artillery officer (back row, far left). [Guelph Civic Museum/M1968X.353.1.2]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/mccrae3.jpg)

From that time until the summer of 1914, McCrae’s life and work were based in Montreal, where he developed his expertise as a doctor and a gifted teacher, and where he found kindred spirits who shared his love of art, music and words. His personality and talents gained him ample friends and recognition.

What made McCrae popular? He was tall, handsome, youthful in appearance and manner, intelligent, charming and humorous, with a smile that denoted “sheer fun, pure gaiety.” He was an excellent conversationalist, a brilliant raconteur and a good mixer. People were struck by his keen mind, straightforward attitude, warmth and openness, such that “he was the last man in the world to be imposed upon.” His intellect, encyclopedic knowledge and exceptional memory marked him out, and an unending fund of light-hearted stories gained him a reputation as the perfect dinner guest who followed Rudyard Kipling’s advice to ensure “all men count to you, but none too much.” Friends ranged from boyhood pals to Earl Grey, Canada’s ninth governor general, writer Stephen Leacock, eminent Canadian physician Sir William Osler, and British politician Leo Amery, who described McCrae as “the most lovable of men.”

The young doctor’s drive for excellence made him an incredibly hard worker, and his relentless schedule was fuelled by his own admission that “I have never refused any work that was given me to do.” With never-ending hospital rounds, teaching, clinics, private patients, medical writing and social engagements, it is no wonder that he complained of pressure and fatigue, and told his mother “I have been at it ding-dong all day and every day.”

McCrae had not been active in the militia for a decade, but he offered his services “either combatant or medical, if they need me.”

In his precious quiet moments, McCrae found an opportunity to write poetry that gave expression to the more reflective side of his nature. From 1901 to 1914, his verse was published in McGill’s University Magazine.

As a bachelor, McCrae indulged his love of travel, ships and the sea, and he crossed the Atlantic on holidays or study visits to Europe prior to 1914. At other times, he escaped the rigours of his professional life to visit family and friends or to go on hunting and fishing trips.

In August 1914, he was on his way to Britain for a summer vacation when the First World War broke out. He understood enough about the latest weapons and artillery to appreciate its likely nature and dire consequences. At the age of 41, he was old to volunteer and had not been active in the militia for a decade, but he offered his services “either combatant or medical, if they need me.”

Appointed brigade surgeon to 1st Brigade Canadian Field Artillery, McCrae proved to be a first-class military medical officer. The foundations that underpinned his life—exemplary service, dedication, responsibility and unshakeable commitment—were evident during the war. Like others of his generation, he felt a high sense of honour toward his country and Great Britain. He possessed an instinct against injustice, and was driven by the kind of integrity that demanded that a personal effort be made.

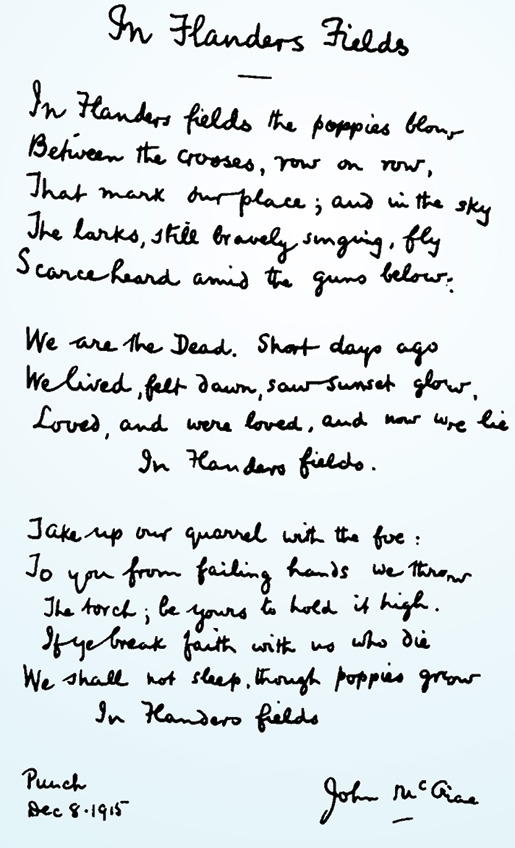

From April 22 to May 9, 1915, McCrae and 1st Brigade Canadian Field Artillery took part in the titanic struggle of the Second Battle of Ypres, which he afterward described as “seventeen days of Hades” during which “every horror that war had, we had at our door.” The experience left a mark on this valiant but sensitive man, and the death on May 2 of his friend Alexis Helmer, a young officer of his brigade, moved him to commit his feelings to verse. The first drafts of “In Flanders Fields” were written in early May 1915, and reworked at a later date prior to the poem’s publication in Punch magazine on December 8, 1915.

![McCrae on his faithful charger Bonfire. [Guelph Civic Museum/M1968X.358.1]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/mccrae4.jpg)

The remainder of McCrae’s war was spent at No. 3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill) near Boulogne, France. He was appointed officer in charge of medicine and was gradually able to recover from the strain of the Second Battle of Ypres, which by his own admission surpassed “all belief till you have been in it.” His former lightheartedness did not return, but his adherence to high standards, discipline and duty to his patients remained absolutely firm.

Aspects of the old McCrae were, however, still seen on occasion. In off-duty hours, he went for peaceful rides on his horse, Bonfire, and often stopped to chat with local children. Young people have a way of seeing beyond appearances, and one girl later gave her impressions of him. He was, she said, “a very straightforward, very gentle man who you could not help liking. Everything about his face indicated someone very special.”

McCrae felt uncomfortable about not being with his former artillery colleagues at the front, but he remained intensely committed to the war and refused to return to Canada before it was won. “In Flanders Fields” voiced his conviction that the fight must continue so that victory would be assured, the Empire preserved, and the horrendous numbers of deaths would not be in vain. He would also have agreed with Kipling—whom he admired and had met in South Africa—who wrote of the need to “loosen first the sword of Justice upon earth,” otherwise “all else is vain.”

McCrae was honoured in January 1918 with a promotion to colonel and an appointment as consultant physician to the British armies in the field. But he contracted pneumonia and meningitis and died on Jan. 28. His legacy survives in his poem, its effect in helping to raise morale and funds, and its integral place in the remembrance of the war dead of the Allied countries. It has also endured through the example of his life, his “career of honour and marked distinction” and his “honourable endeavor.”

McCrae once told his students that it was up to them “to store up for yourselves treasures that will come back to you in the consciousness of duty well done, of kind acts performed, things that having given away, freely you yet possess.”

This says much about the man a former medical colleague referred to as “our hero of heroes.” However, a nurse who knew and worked with McCrae during the war years spoke perhaps most eloquently of this exceptional Canadian: “Was anyone ever more respected and loved than he?”

Advertisement

![Book and cigar in hand, John McCrae relaxes at the holiday home of friends at Kennebunkport, Maine, where he spent a vacation in September 1903. [Guelph Civic Museum/M1968X.436.3]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/mccrae1.jpg)