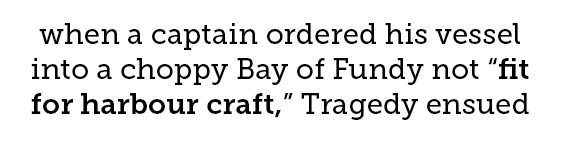

Skipper Harding Wambach stands outside the wheelhouse on Harbour Defence Craft 15, which conducted examination duties in Saint John, N.B., in 1943. [DND]

When Nicholas Monserrat titled his classic account of the Battle of the Atlantic The Cruel Sea, it was no accident. Nearly half of the Royal Canadian Navy vessels lost in the Second World War succumbed to marine accidents.

Patrol boat HMCS Adversus ran aground; destroyer HMCS Skeena dragged its anchor and stranded on the island of Viðey in Iceland; five boats of the 29th Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla burned in a fire in the harbour at Ostend, Belgium; minesweeper HMCS Bras D’Or simply disappeared; armed yacht HMCS Otter caught fire and exploded.

Collision was a constant danger. C-class destroyer HMCS Fraser was sliced in half by anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Calcutta off Bordeaux, France, in June 1940. Its replacement, D-class destroyer HMCS Margaree, was lost three months later in a collision with a ship in the same convoy. Flower-class corvette HMCS Windflower and Bangor-class minesweeper HMCS Chedabucto were also sunk by the vessels they escorted. And lowly Gate Vessel 1, former Battle-class naval trawler HMCS Ypres, was run down by the battleship HMS Revenge at the entrance to Halifax Harbour.

Now the Canadian navy has added a new name to the list of vessels lost at sea during the Second World War: Harbour Defence Craft 15.

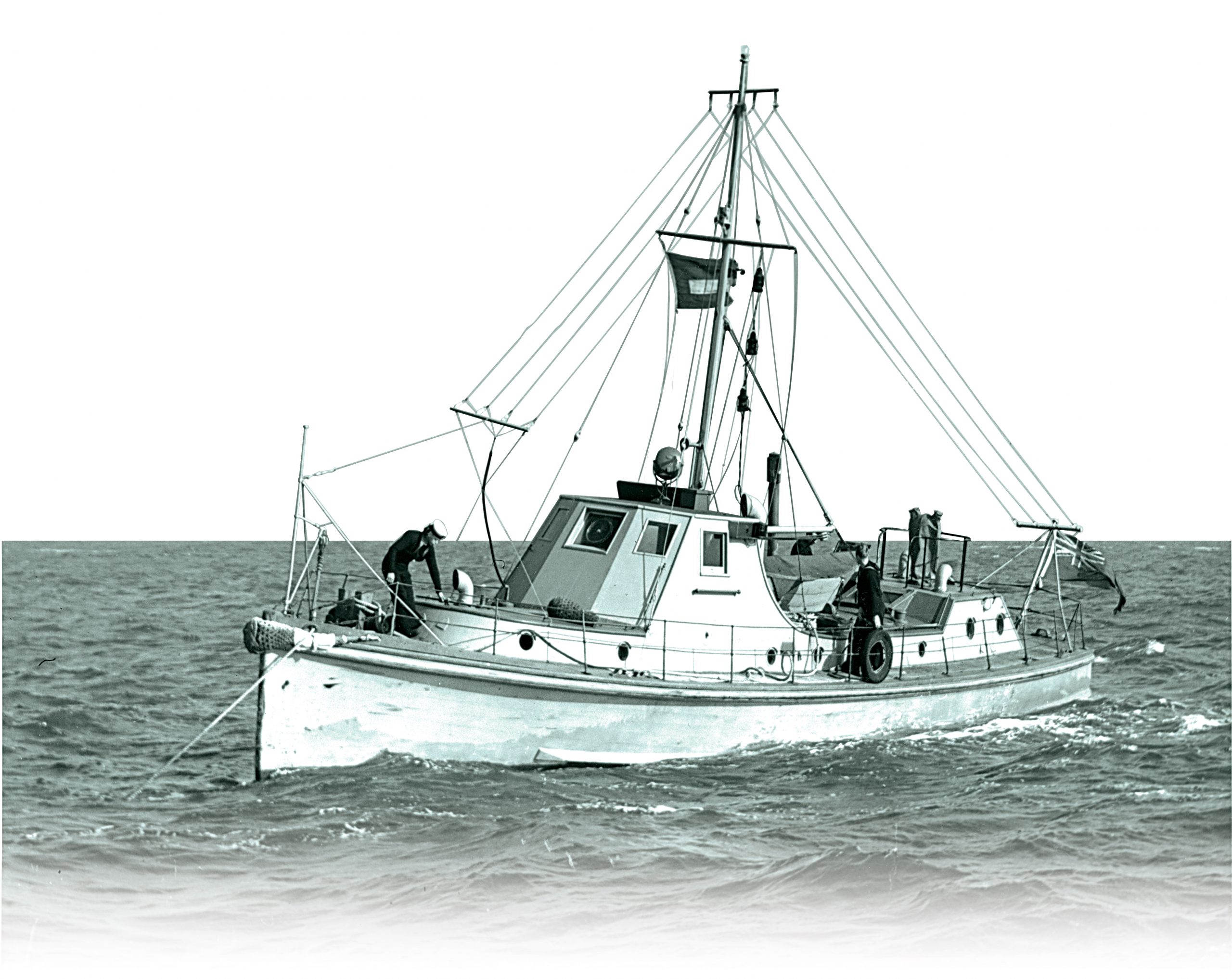

Five soldiers stationed on Partridge Island in 1943 witnessed the HDC 15 incident. Offshore, ships in the examination anchorage wait to be inspected. [DND]

To be sure, HDC 15 was a modest vessel: built of wood in Shelburne, N.S., in 1940 and barely 48.5 feet long and 13 feet wide. Its two 225-horsepower gas engines produced a maximum speed of 15 knots and it could cruise for 15 hours. A slightly raised cabin provided standing room for the crew below decks, space for a small galley, and an enclosed wheelhouse. HDC 15 carried a 14-foot dory as a tender, a searchlight and one depth charge chute (without the charge).

In December 1942, after service in Halifax, HDC 15 made the passage to Saint John, N.B., to help the local naval establishment, HMCS Captor II, handle the winter surge in traffic. Between November and May, Saint John was Canada’s busiest commercial port, handling 40 to 60 ocean-going vessels a month. These included Canada’s traffic to neutral countries, notably the Republic of Ireland and, in 1943, Swedish relief ships carrying Canadian grain to Nazi-occupied Greece.

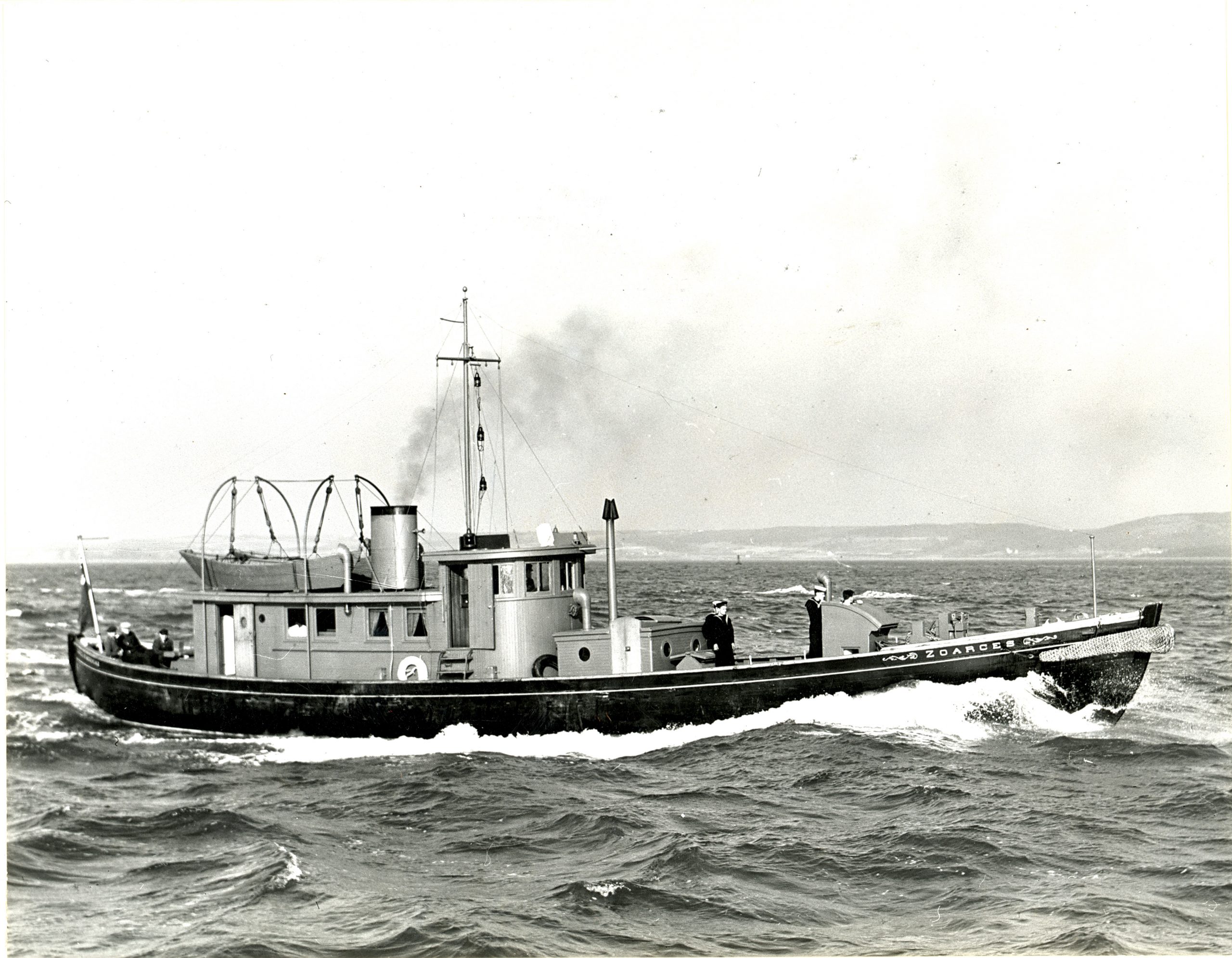

By early 1943, Captor II’s fleet consisted of about a dozen vessels. Isles-class trawlers HMCS Anticosti and HMCS Magdalen provided anti-submarine patrols for the outer harbour. The former tugboat HMCS Murray Stewart and the sleek schooner-like HMCS Zoarces conducted examination services, while a clutch of eight much smaller vessels supported the examination services and provided inner-harbour patrols.

Captor II’s fleet was extremely busy through the winter of 1943. In March, 47 ships arrived, and 39 ships left in eight convoys for Halifax. By the end of the month, 23 ocean-going steamers lay alongside, with more waiting in the examination anchorage south of Partridge Island. April was even busier; 70 ships cleared the port that month, including seven Swedish and four Irish vessels. “A berth is seldom vacant for more than a few hours,” Captor II reported in May. Shuffling shipping to and from the exposed examination anchorage kept it all ticking along.

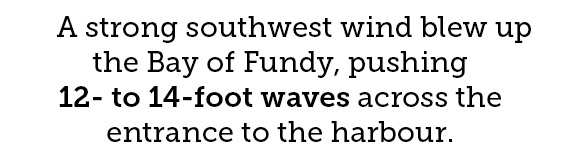

HDC 37 was typical of the small vessels that formed the inner-harbour defences of several Canadian wartime ports. [DND]

On April 14, 1943, a strong southwest wind blew up the Bay of Fundy, pushing 12- to 14-foot waves across the entrance to the harbour. By noon, the wind had pushed the Swedish relief ship SS Monga Barra across the inner harbour and stranded it alongside the Atlantic Sugar Refineries wharf. Zoarces, coming in from a stint of examination duty, arranged for harbour tugs to pull Monga Barra off, and then went alongside and dismissed its crew for the day.

By 1:50 p.m., it was clear that the local tugs needed help, so Murray Stewart was ordered in from the examination anchorage to assist. Zoarces was ordered to resume examination duties, but its crew was already scattering to homes and bars around the city. Getting them back would take time.

HDC 15, standing by at Pier 5 in Saint John West, was ordered to meet Murray Stewart, take off the examination officer, and stand by as the examination vessel until Zoarces could pick him up.

The transfer never happened.

At roughly 2 p.m., HDC 15 cast off and headed down the harbour with six of the usual crew of seven aboard. (Able Seaman F. McKenna had stood duty watch the night before and was excused for the day.) In addition to Skipper Harding Robertson Wambach, HDC 15 carried a motor mechanic, an able seaman, a signaller and two ordinary seamen.

Motor Mechanic Thomas James Rourke, born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1916 and raised in Saskatoon, joined the RCN in March 1940 and served in small vessels on the East Coast. When he joined Captor II in September 1942, his wife Wilma moved to Saint John to be with him.

Able Seamen Odin Arthur Elliott, 22, was an experienced seafarer who knew the Bay of Fundy well. Before he joined the navy in April 1941, his ship was the schooner Rayo from his hometown of Apple River, N.S., near the head of the bay. His forearms were suitably tattooed, including an anchor. Elliott had arrived in Saint John aboard HDC 15 in December, leaving his wife Beulah behind.

Wambach’s signalman was Lawrence Cyril Jasper, 21, an electrician’s apprentice from Toronto. After joining the navy in 1940, Jasper had struggled to pass the signalman’s test, but finally qualified with a rank of ordinary signalman. Like the others, he had served in several small boats in Halifax before his posting to Captor II. His young wife Mary had also moved to Saint John.

Ordinary Seaman Joseph W. Nodwell, 20, was a Saint John lad from the local reserve division HMCS Brunswicker. He went on active duty in March 1942. He also returned to Saint John in December aboard HDC 15.

Ordinary Seaman John Patrick Daly, another Toronto native and just a few months shy of his 20th birthday, rounded out the crew.

HMCS Murray Stewart conducted much of the examination duties in Saint John. [DND]

As HDC 15 motored down the harbour, past the stranded Monga Barra, Wambach met HDC 37 and discussed the weather with Skipper Frederick Durant. Durant warned Wambach that conditions were not “fit for harbour craft,” advice confirmed by the harbour pilot aboard HDC 37. Both advised Wambach to turn back. When Wambach resumed his course seaward, Durant turned HDC 37 to watch him go and to stand by if HDC 15 got into trouble.

HDC 15 met Murray Stewart at the bell buoy northeast of Partridge Island at 2:47 p.m. That point was fully exposed to the long southwesterly fetch, and seas were running high. When Wambach turned his small craft around to follow Murray Stewart into the lee of the island, HDC 15 could not hold the course. Waves pushed its stern around repeatedly until HDC 15 finally wallowed in a trough. The next large sea rolled it over.

HDC 15 disappeared “in a flurry of foam,” according to Chaplain A.R. Perkins of the 3rd (New Brunswick) Coast Regiment, who watched it all from the veranda of the sergeant’s mess on the island.

Skipper Eric Caines of Murray Stewart immediately ordered his crew on deck with lifebelts and the ship’s boat cleared to launch. He turned his ship to help.

Three men were soon seen in the water: one clinging to the dory and two to what looked like a deck hatch. Murray Stewart got to within 15 feet of the pair on the hatch, and threw lifelines and kisby rings, but to no avail. The seas carried the men away, and their heavy foul-weather gear pulled them down.

The rescue operation quickly drifted into shoal water north of the channel, where the sea rose steeply and became very confused.

Murray Stewart, 119 feet long with powerful tugboat engines, was soon in danger. When waves swamped the stern and swept away the boat, Caines ordered his men inside and tried to go astern, back into the channel. When that failed, Caines ordered full power and a turn to starboard. As Murray Stewart came around, it met the full force of the sea. Within seconds a wave crashed against the wheelhouse, taking out three windows and the ship’s communications.

Mate Jonathan W.H. Tremaine, a veteran of 16 years at sea in the Saint John area, told the subsequent board of inquiry that those seas were 20 feet high. He may have been right: Murray Stewart’s wheelhouse was 16 feet off the water.

Meanwhile, Skipper Durant brought HDC 37 within 100 yards of the overturned vessel before backing out because his ship “was becoming unmanageable.”

In the circumstances, nothing could be done for HDC 15 and its crew.

While examination vessel HMCS Zoarces dealt with a ship stranded in the harbour, HDC 15 stepped in. [DND]

That night, a badly battered HDC 15 was found upright on the east side of the Courtney Bay breakwater. Wambach’s body was in the forward cabin. Rourke’s body was found a few minutes later among the rocks. Daly, Jasper, Elliott and Nodwell were missing. By noon on April 15, heavy seas had destroyed what remained of HDC 15.

A board of inquiry convened in Saint John on April 17, heard testimony from 18 witnesses, including five soldiers from Partridge Island and six from vessels nearby at the time. The burden of the testimony focused on weather and sea state.

The inquiry concluded that “conditions prevailing at the time were too bad for the HDC 15 to weather.” The blame for the loss of HDC 15 was laid squarely on Wambach: “Overzealousness on the part of Skipper Harding Wambach, R.C.N.R. in endeavouring to carry out the order received by him, was a primary cause.”

By then Wambach’s body was already on its way to East LaHave, N.S., for burial. Rourke was buried near his wife Wilma’s home in Sillery, Que. The sea eventually gave up other remains. At the end of October, a badly decomposed body identified from clothing as Elliott came ashore near Red Head. His remains were buried at Fairview Cemetery in Halifax. Over the next two weeks, a torso and a skull were also found at Red Head. These were buried in Fern Hill Cemetary in Saint John in separate graves as unidentified RCN sailors. No other remains were found.

Like the men in those other RCN vessels lost to the cruel sea, the crew of HDC 15 died in the cold waters of the Atlantic Ocean while on active service, their passing marked only by scattered graves and inscriptions on the Halifax Memorial. But no longer: in 2019, HDC 15—the only Canadian harbour defence craft sunk in wartime operations—was added to the navy’s official list of wartime losses.

A good seaman

[DND]

Skipper Harding Robertson Wambach was born in East LaHave in Lunenburg County, N.S., on Nov. 20, 1912. By the time he joined the navy in April 1940, Wambach had spent years in the “coasting trade.” After training on HMCS Cartier, he joined his father and brother operating small boats in Halifax Harbour.

Wambach was posted to Saint John in July 1942, where he

quickly earned a reputation for his knowledge and skill as a seaman and officer. He often served as an examination officer (known as XO), checking shipsʼ credentials, verifying cargo manifests, fuel requirements and mechanical defects. As an XO, Wambach had been transferred at sea on “numerous occasions.”

The consensus of his peers was that Wambach was a good skipper. Testimony at the board of inquiry described him as “a conscientious, able seaman and pilot” and “a capable and efficient officer” who was “particularly conscientious about the way he kept his boat.”

Advertisement