Sharon Adams sits down with Major Greg Miller, Directorate History and Heritage for the Canadian Armed Forces to discuss the history of one of the most famous instruments used in military history: The Bugle.

[The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum]

The clear call of bugles signalled both the beginning and the end of First World War fighting in Mons, Belgium.

“The bugles sounded the call to arms…. The Germans had advanced suddenly to within striking distance,” wrote Daniel Desmond Sheeham in The Munsters at Mons. Outnumbered and outgunned in their first battle on Aug. 23, 1914, the British and French retreated and Mons was occupied by Germany for more than four years. On the last day of the First World War, the Canadian Corps wrested it back.

On the morning of Nov. 11, 1918, the 49th Battalion (Edmonton Regiment) formed up—surrounded by a celebrating throng—in Mons. “We stood for hours waiting for the King of the Belgians,” recalled Private Neville Jones. “After the speeches were made, the bugle was sounded” at 11 a.m. The war, at long last, was over.

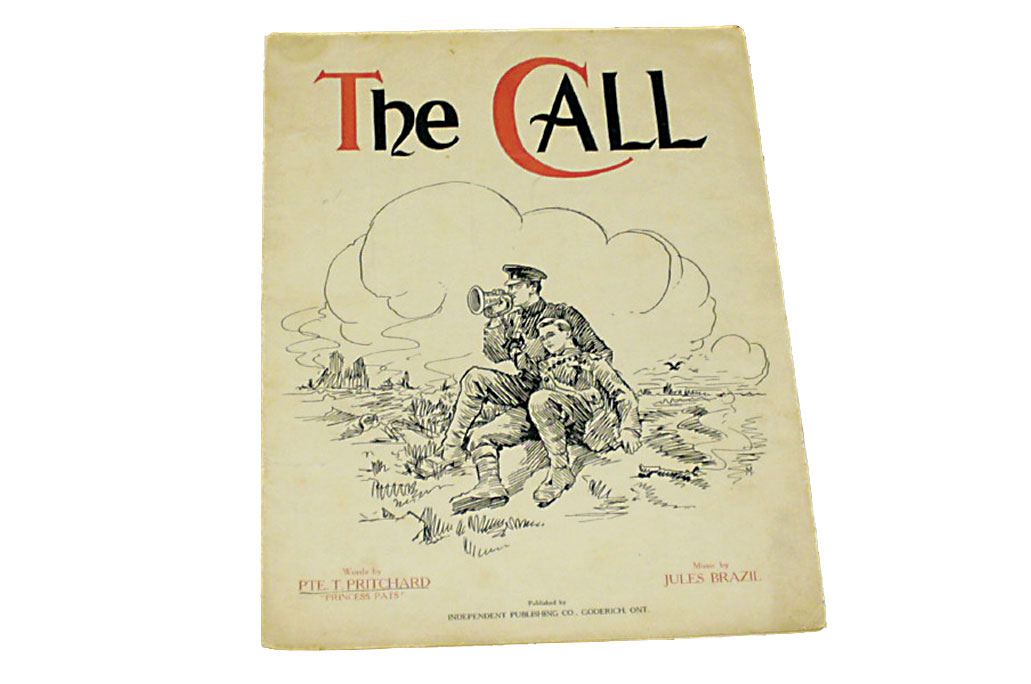

A bugle is prominent on the cover of sheet music from the First World War. [McMaster University]

The mists of history have obscured the identity of the ceasefire bugler, but his bugle survives to this day, a treasured artifact in the museum of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment, which perpetuates the memory of the 49th Battalion.

Returned to Canada, it graced the officers’ mess for years and was turned over to the regimental museum in 1982. The bugle was used to sound the mess call at regimental reunion banquets.

An inscription on the 49th Battalion’s bugle testifies it was blown in Mons at an Armistice ceremony, while the brass instrument shows the dents and marks of hard use. [The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum]

For centuries before the wristwatch was affordable, the bugle (or trumpet) called out the day’s routine in garrison or orders in the field. There were distinctive calls to wake troops up, call them to eat, tell them to start and stop their duties, call them to assembly and, on Sunday, to church. On the battlefield, horns or drums were used to communicate over battle’s din and great distances. They signalled when and where to move, when to start and stop firing.

A stained-glass bugler (left) blows “Last Post” in a memorial to Royal Military College fallen. [Royal Military College Museum]

In skirmishes after the Battle of Mons, said British private George Holbrook, “we always knew when the Germans were coming because they blew a bugle.” At the Battle of Le Cateau in 1914, deceptive German buglers sounded the British ceasefire call, but were unsuccessful in tricking the Tommies.

The importance of the bugle in regulating everyday military life dwindled as communications technology improved and personal timepieces became affordable. But at specific times throughout the day, bugle calls (mostly recorded) are still broadcast in United States military installations to promote discipline, maintain pride and foster unity. “They offer soldiers and family members the chance to unite several times a day, and honor the colors they are fighting to protect,” says a U.S. Army website.

In Canada, “Last Post” is perhaps the most recognizable bugle call, played before the silence at commemorative services. Originally called “Setting the Watch,” it indicated the end of the day’s duties. In the 19th century, buglers began playing it at funerals to signify the end of life’s duties. It is traditionally followed by “The Rouse,” once played to get soldiers out of bed. At remembrance services, it represents the dead awakening to a better world and is a call to the living to return to their duties.

Bull’s horns (above) were fashioned into cups and early musical instruments, including war horns. [iStock]

Fast facts:

• The bugle is one of the simplest brass instruments. It has no valves or other means of altering pitch, other than through the player’s lips, face muscles, tongue and teeth interacting with the mouthpiece.

• Standard bugle calls consist of only five notes.

• The bugle was first used by foot regiments, superseding the drum, to relay instructions from officers to soldiers in battle.

• In Middle English, the word ‘bugle’ means ox. Ox horns used to sound hunting signals were known as bugle-horns; they were also used as musical instruments and as drinking horns.

Advertisement