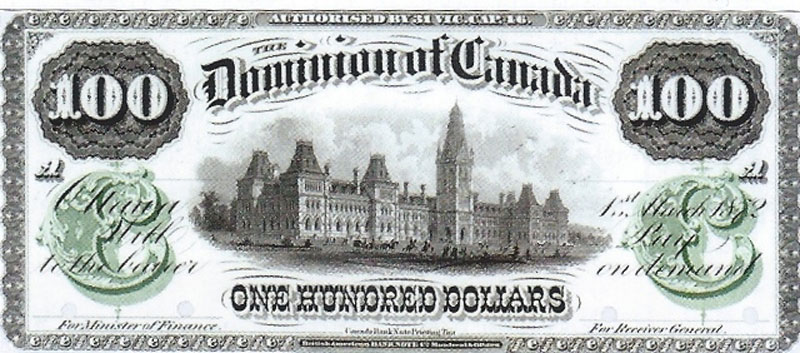

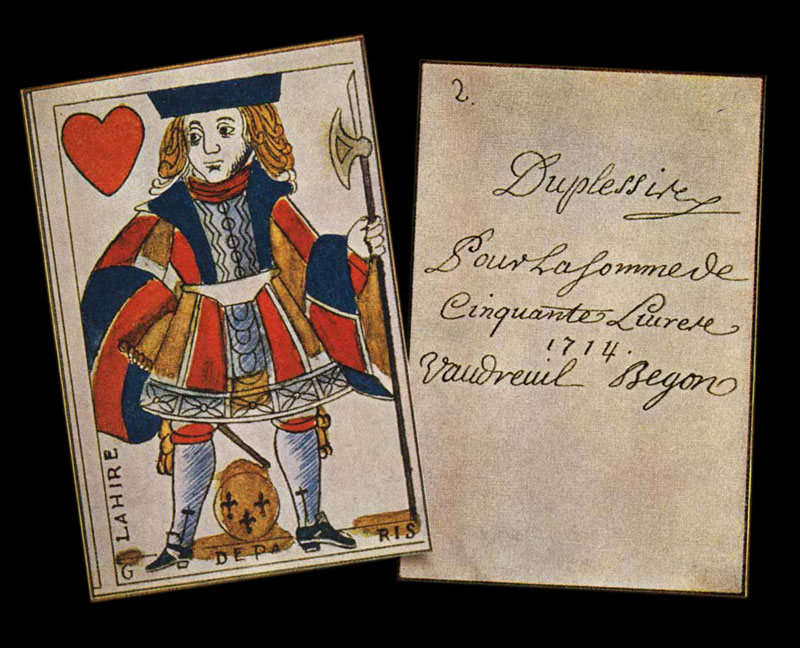

Cards used as currency in New France circa 1714. [Collection Nationale De Monnaies, Musée De La Banque Du Canada]

In the 17th century, the French government sent silver coins to its colony in Quebec, intending them to become common currency.

But those being dangerous times, civil servants and merchants tended to hoard them.

By 1685, there was a serious coin shortage. Worse, the military payroll from France was delayed. Something had to be done—it’s never a good idea to annoy men armed with muskets and swords.

He solved the problem by issuing promissory notes to soldiers on the back of playing cards that could be redeemed several months later.

“I have found myself this year in great straits with regard to the subsistence of the soldiers,” New France Intendant Jacques de Meulles wrote to the French government. “You did not provide for funds, my Lord, until January last. I have, notwithstanding, kept them in provisions until September, which makes eight full months.”

He had used up his own funds and had run out of friends from whom he could borrow.

He solved the problem by issuing promissory notes to soldiers on the back of playing cards. The cards could be redeemed several months later when a new supply of coins arrived from France.

It was the first government-issued paper money in the western world, according to economist Michael Sproul, author of A Quick History of Paper Money.

As history marched on, British colonies in North America managed their own currency, which made trade among them rather complicated.

The British wanted the colonies to use the pence, shillings and pounds sterling of their currency system.

“A similarity of coinage produces reciprocal habits and feelings, and is a new chain and attachment in the intercourse of two nations,” said in a debate in Lower Canada’s House of Assembly in 1830.But most pre-Confederation colonies and provinces leaned toward the dollar, the currency system used by their biggest trading partner, the United States.

In 1851, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia worked out an agreement to use decimal currency. The Canadian legislature subsequently passed an act requiring provincial accounts be kept in dollars and cents, says A History of the Canadian Dollar by the Bank of Canada.

In those days, legislation had to be given the final stamp of approval in Britain, which delayed confirmation on a technicality.

A compromise was struck—the Currency Act of 1853 recognized pence, shillings and pounds as well as dollars and cents as units of Canadian currency.

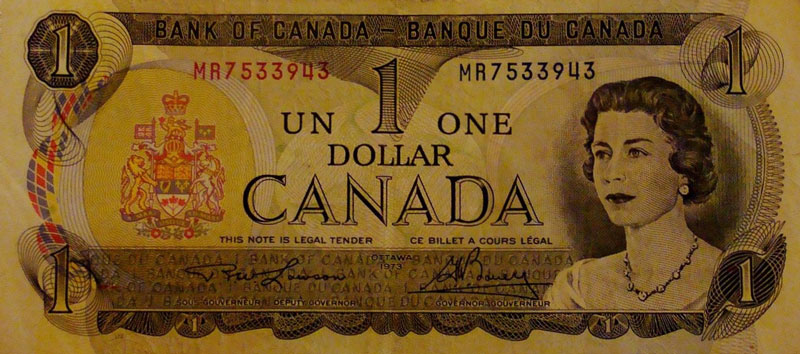

That all changed after Confederation, when the new Dominion assumed jurisdiction over currency and banking and established uniform currency measured in dollars, cents and mills (a thousandth of a dollar) and established exchange rates for British pounds and American dollars.The last green $1 bill rolled off the press at the Canadian Bank Note Company on April 20, 1989. It was replaced by a dollar coin, dubbed the loonie, a double entendre reflecting both the loon on its front and opinion of citizenry of the day who thought replacing the bill was a loony idea.

The $2 bill was retired in 1996 and replaced with a coin featuring a polar bear. This is popularly known as the toonie. Is it a combination of the words two and loonie, or was it a reference to Looney Tunes, the animated cartoon series, and a reflection of the continuing opinion of the Canadian public about the need to eliminate small-denomination paper currency?

Advertisement