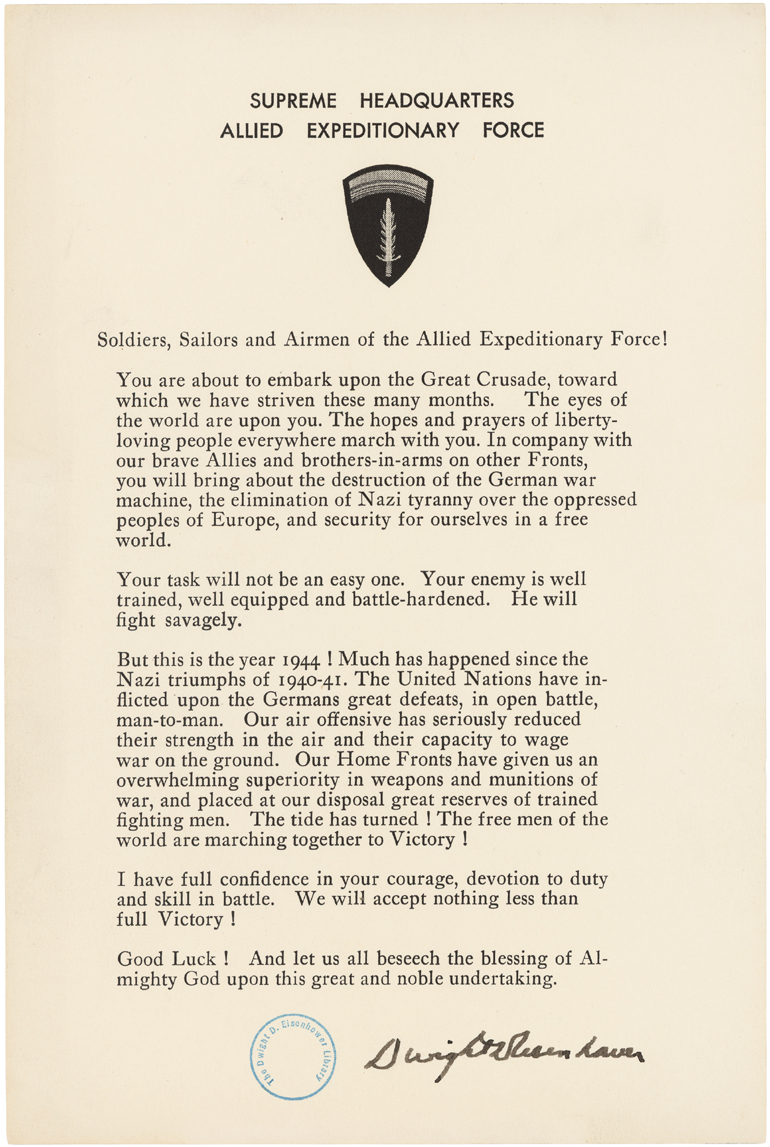

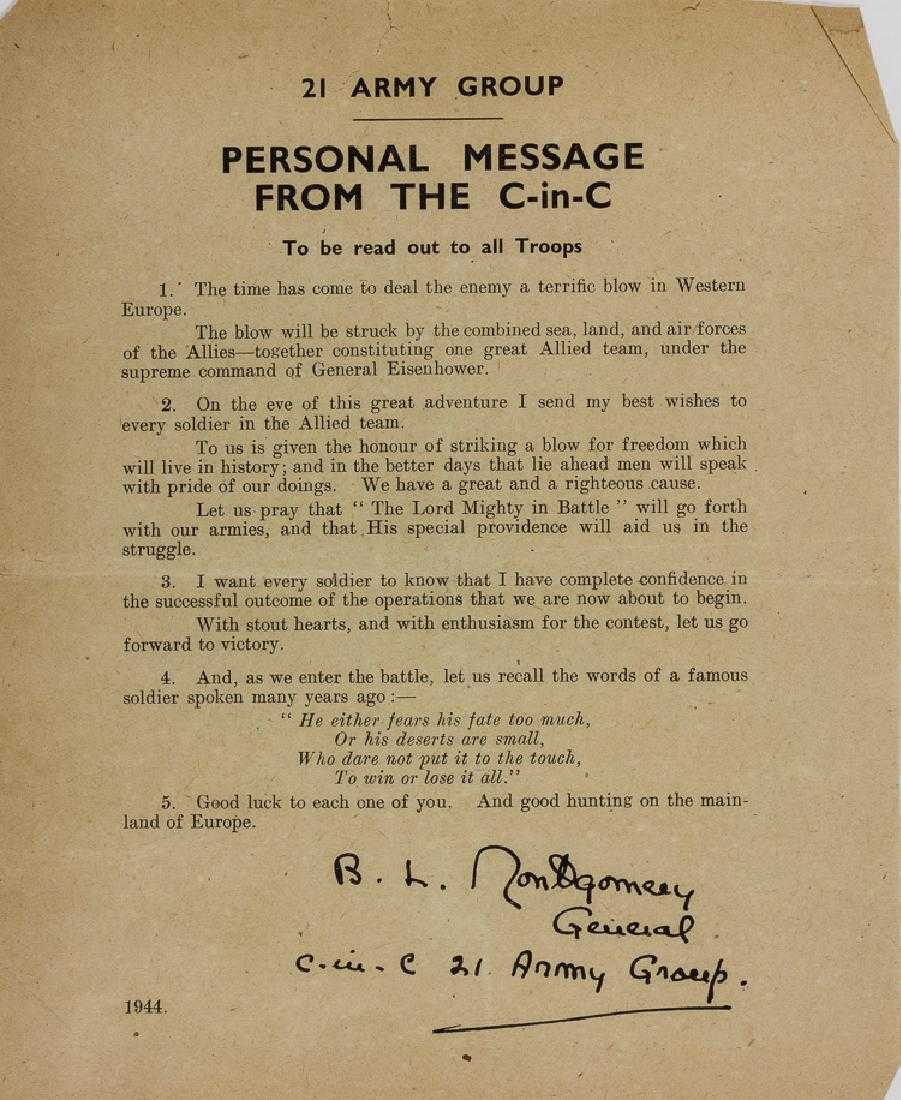

The American employed soaring oratory in calling D-Day troops to “the Great Crusade.” The Brit summoned the words of a 17th-century soldier-poet as he urged the “team” on in their “great and righteous cause.”

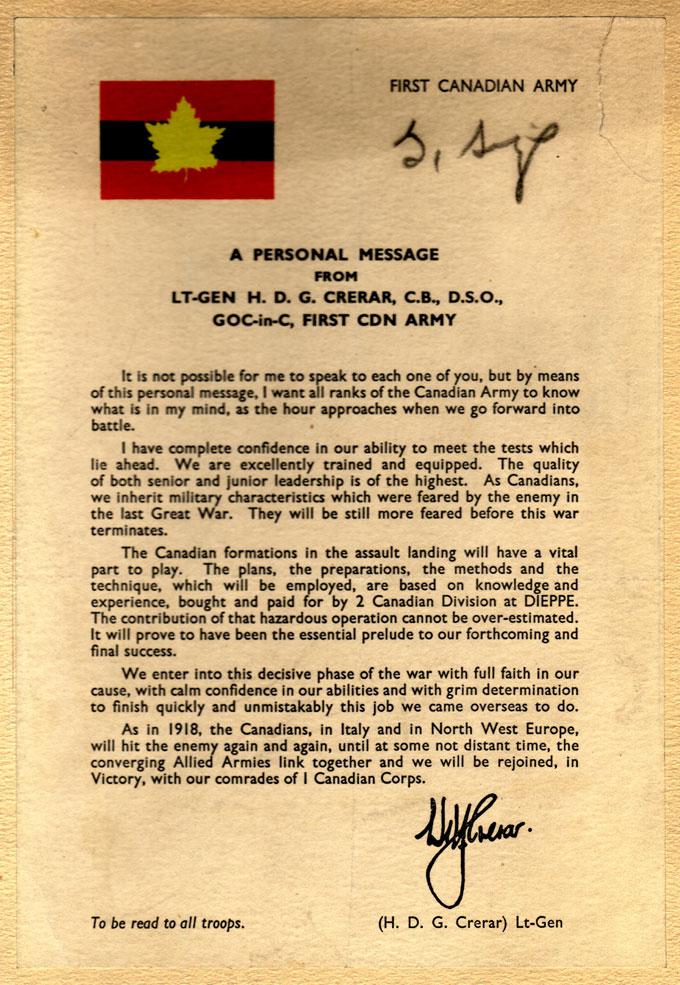

The Canadian, on the other hand, reminded his troops of the “knowledge and experience bought and paid for” by brothers-in-arms who had gone down to abject defeat at Dieppe two years earlier.

The generals commanding Allied forces on D-Day took different tacks in their efforts to inspire soldiers boarding ships and aircraft bound for the greatest seaborne invasion the world has ever seen.

The invaders were embarking from Portsmouth, England, early on the morning of June 6, 1944—five divisions, or 150,000 ground troops, in an armada of 6,900 vessels landing on five beaches across 80 kilometres of heavily defended French coastline.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower meets with the troops before D-Day in 1944. [AP]

At a single page each, the messages—orders of the day, actually—were exercises in brevity and the power of the word. Like Abraham Lincoln’s 272-word Gettysburg address—shorter, in fact—they packed a mighty punch.

The American, Dwight D. Eisenhower, spoke of high ideals and the blessings of “Almighty God” in his one-page order of the day. The Brit, Bernard L. Montgomery, summoned “stout hearts” and “good hunting” before citing James Graham, the 1st Marquess of Montrose, a Scot who has been called “the bravest man in England.”

Both addressed the combined invasion forces of Canada, Britain and the United States.

The original draft of Lieutenant-General Henry D.G. (Harry) Crerar’s D-Day address. [Wartime Canada]

“As Canadians, we inherit military characteristics which were feared by the enemy in the last Great War,” Crerar said. “They will be still more feared before this war terminates.”

The Canadians had been awarded their own beach, codenamed Juno at British prime minister Winston Churchill’s behest after he’d put the kibosh on the intended fish name, Jelly.

Nestled between the British beaches Gold and Sword on the invasion’s left flank (the Americans dispensed with fish names altogether, going with Utah and Omaha on the right), Juno included the French villages of Courseulles and Bernières.

They were well southwest of Dieppe, where 3,623 of 6,086 men who made it ashore—mostly Canadians—were either killed, wounded or captured in an ill-planned and poorly supported raid on Aug. 19, 1942.

The sacrifice earned them the right to do it again, this time in Normandy for what would prove to be the ultimate Allied gamble. Crerar, commander of the First Canadian Army, paid tribute in his pre-invasion speech to the efforts of the hard-hit 2nd Canadian Division at Dieppe, where the objective was simply to seize and briefly hold a major port, both to prove it was possible and to gather intelligence.

Some have said Dieppe provided invaluable lessons for the D-Day planners. Others have characterized it as a criminal waste of human lives. Crerar came down on the side of the former.

“The contribution of that hazardous operation cannot be over-estimated,” he said. “It will prove to have been the essential prelude to our forthcoming and final success.

“We enter into this decisive phase of the war with full faith in our cause, with calm confidence in our abilities and with grim determination to finish quickly and unmistakably this job we came overseas to do.”

In contrast to the Canadian’s relatively pragmatic, plain-spoken message, Ike and Monty’s speeches were inspiring in the classical sense. Eisenhower alluded repeatedly to the righteousness of the Allied cause, while Montgomery began by almost likening the invasion to an English football match with his references to the “team” and “enthusiasm for the contest.”The notoriously difficult and frustratingly slow-moving Monty, who made his name two years earlier with his Desert Rats against Erwin Rommel in North Africa, recalled the words of the soldier-poet Graham.

Graham was a Scottish nobleman who won spectacular victories while fighting on behalf of King Charles I in the English Civil War of the 1640s and ’50s. A captain general, he fought brief but effective military campaigns, using the element of surprise to overcome his opponents, even when outnumbered.

In his poem “My Dear and Only Love,” Graham wrote the words Montgomery quoted 300 years later:

He either fears his fate too much,

Or his deserts are small,

That puts it not unto the touch

To win or lose it all.

“Good luck to each of you,” Montgomery concluded. “And good hunting on the main-land of Europe.”

Canadian Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and Canadian General Henry Crerar at Allied Headquarters in February 1945. [Wikimedia]

“You are about to embark on the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months,” declared the supreme Allied commander. “The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.

“In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

“Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped, and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.

“The tide has turned. The free men of the world are marching together to victory.

“I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty, and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full victory.

“Good Luck! And let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.”

An estimated 5,000 Allied troops, including 335 Canadians, would die that day. Eleven months later, their comrades in arms would march into Berlin.

—

This is the first of three Front Lines columns on D-Day.

Advertisement