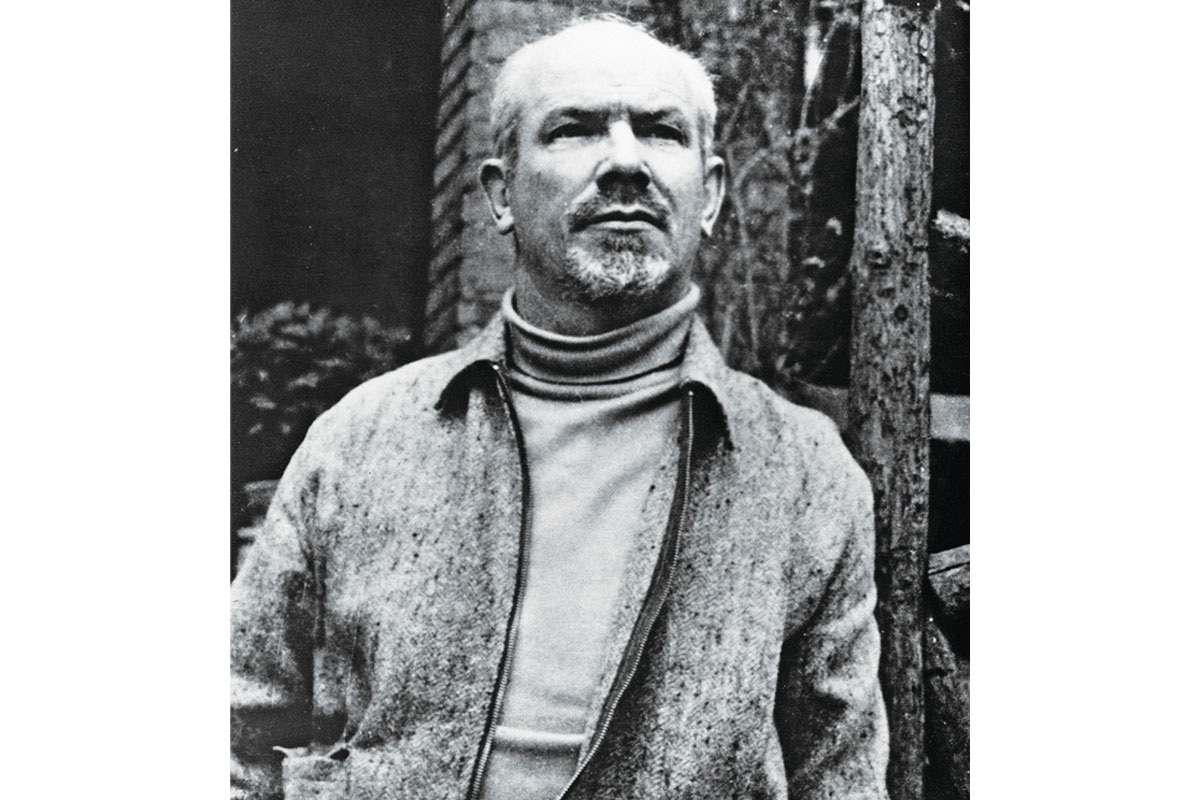

On Feb. 8, 1937, some 150,000 Spanish civilians fled Málaga and General Francisco Franco’s closing Nationalist forces. Confined to a narrow coastal road, the refugees soon met Canadian doctor Norman Bethune. [Wikimedia]

In Canada, a third of the labour force was unemployed, many people relied on government relief to survive, and a network of camps opened across the country to provide work and room and board for the legion of unemployed young men.

In 1936, the elected republican government in Spain faced a military coup headed by General Francisco Franco, who was backed by the fascist governments in Italy and Germany. The republicans put out a plea for international help, and tens of thousands of idealistic young men and women from many countries flocked to Spain to fight fascism.

Western governments feared they would be radicalized and return home to foment revolution. In the spring of 1937, Canada joined other countries that made it illegal for their citizens to enlist in foreign wars.

Nonetheless, by mid-July, nearly 1,600 Canadian volunteers had gone to Spain to fight with the republications. At least 400 died there. The Canadians joined various international brigades, but collectively were known as the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, or Mac-Paps, named after leaders of Canadian rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada a century earlier.

The volunteers were for the most part working class—unemployed miners, loggers and farmers. Perhaps the most famous to serve was Norman Bethune, who with nurse Rosaleen Ross, operated a mobile blood-transfusion service.

The Mac-Paps fought in five major campaigns. The casualty rate was atrocious, for the republicans generally, and the international brigades particularly. They were hobbled by a lack of weapons, war materials and supplies. It has been said that by the time they were honourably discharged by the Spanish government in 1938, among the hundreds of wounded, there were only 35 Mac-Paps left on their feet.

Under blockade by Western governments, the republicans lost, no match for the high-tech weaponry, tanks and aircraft and 100,000 experienced troops contributed by the fascist governments in Germany and Italy.

When they returned home, Mac-Pap survivors were treated with suspicion, their allegiance questioned. Although they had fought fascism in the 1930s, many had trouble enlisting to fight fascism in the Second World War. Intelligence dossiers were kept on many throughout their lives.

Scattered across the country are stones, stelae and statues to the memory of the Mac-Paps. In 2001, a national monument containing all their names was erected in Ottawa at Green Island Park on Sussex Drive.

Jules Paivio, an architect and educator who fought for decades for recognition for his comrades, was the last of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and died in 2013 at the age of 97, in Sudbury, Ont.

“The main thing was a terrible fear of fascism taking over,” he said in a CBC interview. “I didn’t expect to come back…but it seemed a worthwhile thing.”

Advertisement