The 1st Canadian Division arrives in London later that month. It would be years before the Canadians would see significant action. [DND/LAC/PA-137186]

The soldiers of the 1st Canadian Division arrived in England before the end of 1939, and each year during the Second World War, more Canadian troops came. The overseas force eventually grew to three infantry and two armoured divisions and two armoured brigades. One infantry brigade from the 1st Division was put on standby to fight in Norway in May 1940, but the War Office in London cancelled the deployment. The Germans soon occupied the country.

Another brigade from the 1st landed in France on June 12 and 13—after Dunkirk—but received orders to return to Britain shortly afterward as French resistance to the blitzkrieg collapsed. There was a minor raid in August 1941, when some 500 infantry from the 1st Division landed on Spitsbergen, a northern Norwegian island, and successfully destroyed coal mines and removed civilians.

Finally, 50 soldiers from the Carleton and York Regiment formed part of a raiding force that attacked enemy positions at Hardelot, near Boulogne, France, in April 1942. Through mischance, the Canadians did not disembark, and the raid was unsuccessful.

After some two-and-a-half years in Britain, the Canadians had yet to see any fighting. “What does your soldier do?” one British woman was supposed to have asked a friend. “He’s not a soldier,” came the reply, “he’s a Canadian.” That smarted.

So, what did the growing numbers of Canadian soldiers do in Britain? They trained, trained and trained some more. The men of the 1st Division had arrived largely unprepared and unequipped for war. Robert Kingstone, a young lieutenant in the artillery, later recalled, “We had some small arms. But, for instance, the officers didn’t have a revolver…. There were some rifles, Enfields and bayonets, but virtually, 1st Division consisted of soldiers only.”

Canada was unprepared for war because the tiny armed forces had received little funding or training in the two decades since the end of the Great War. The men did their individual training, practised section and platoon tactics, and gradually learned how to fire their artillery and drive on British roads. They were certainly not battle worthy, as the Canadian Corps commander Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton claimed. When the aforementioned Norwegian and French enterprises were abandoned, the units were lucky to have not faced the Germans. The subsequent divisions that came to England were somewhat better trained when they arrived, but they too, required much more preparation for war.

But, after the fall of France, the British troops that had been rescued at Dunkirk were so weak and disorganized that the Canadians were possibly the best equipped and best trained of the forces defending Britain. As Kingstone put it, by then “1st Division was the only real equipped force in the British Isles. And Lord knows, we were pretty green. However, for morale reasons, they moved us all over England and Wales. We ended up on the south coast where we manned beach defences.”

As the invasion threat declined in 1941, the Canadians moved off the beaches and trained some more. And they needed it. Gunner Alan Troy recalled his battery’s training: “From arrival in September 1940 until we left for a concentration area near Dover in May of 1944, pending departure for Normandy, it was all go. We took part in live firing practice, course shoots, technical shoots, battery fire movements, anti-tank practice, divisional concentration and barrages. Training in one form or another was always a priority.” However, A. Bruce Medd, an artillery captain, remembered being in a convoy that “arrived at Ashdown Forest in the afternoon. We stayed there until the evening and then we were sent back. We were supposed to have guides,” he continued, “but evidently that didn’t happen. The convoy got lost. It was a real lesson to us. From then on we learned how to map read and carried maps with us.”

Navigation in England was a challenge. As Gerald Andrews, then a lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Engineers, put it in a letter home in August 1940: “The whole country is stripped of all signposts, place names…it is a real job to pilot a convoy of army vehicles from one place to another.” But, he said, “My experience with maps has enabled me to act as ‘navigator’ of these land convoys.”

The root of the problem was that responsibility for training had been farmed out by General McNaughton to his subordinate commanders in the divisions, brigades, battalions and regiments. These officers were largely Great War veterans, men who had served with distinction at the front and in the interwar militia. Their experience was out of date and there was no one to push them hard.

McNaughton was not interested in training so much as in tinkering with weapons and scientific gunnery, and the division commanders under him—Generals George Pearkes of the 1st Division, Victor Odlum of the Second and Charles Basil Price of the Third—were personally courageous, but unable to push training. Some regimental commanders refused to send their officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) on courses for fear they would be snatched away; other units, Major Bert Hoffmeister of the Seaforth Highlanders remembered, had no training manuals unless officers purchased them.

Canadian infantrymen board a ship in Halifax on Dec. 7, 1939, en route to Britain. [Audrain/LAC/PA-034186]

Meanwhile, the troops were bored and frustrated, preoccupied with leave, local women and a desire for cigarettes to give as gifts or to barter with. Bombardier Harry Clark wrote his parents that: “You don’t have to worry about me picking up with ‘strange women’ as you call it, because even if I do go out with any girls they have to be the best, because I am a mighty particular man.”

Most Canadians did not seem as particular. Private Edward Bryer of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders told his family that “cigarettes and tobacco and papers are very scarce. You can buy English Cigarrettes [sic] here but they are drier and not like ours at all.”

Cigarettes “are vital” one officer wrote to his mother, and almost every soldier urged family and friends to send tax-free smokes—300 cigarettes could be sent overseas for $1.

Most of the men were young and not well educated, but they could drive. They had joined up to fight the Germans and they were eager to learn. Artillery Officer Elmer Bell wrote home that “this life isn’t so bad apart from homesickness. All the boys would like to get it over with and get back to Canada, but they don’t want to go back without licking Jerry and I think they can do it.”

The situation did not begin to change until December 1941 when Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery took over the command in which the Canadians served. Montgomery was one of the few British senior commanders who had done well in France in 1940. He could see the Canadians were good material, so he began to inspect their units, talking to officers and NCOs.

“I am working like Hell here we are taking our Basick [sic] Training all over only twice as hard.”

Prime Minister Mackenzie King speaks with Major-General George Pearkes in London in 1941.[DND/LAC/PA-132774]

A Canadian soldier secures his gun to a bicycle during training in England in April 1943.[Lieutenant Jack H. Smith/DND/LAC/PA-211637]

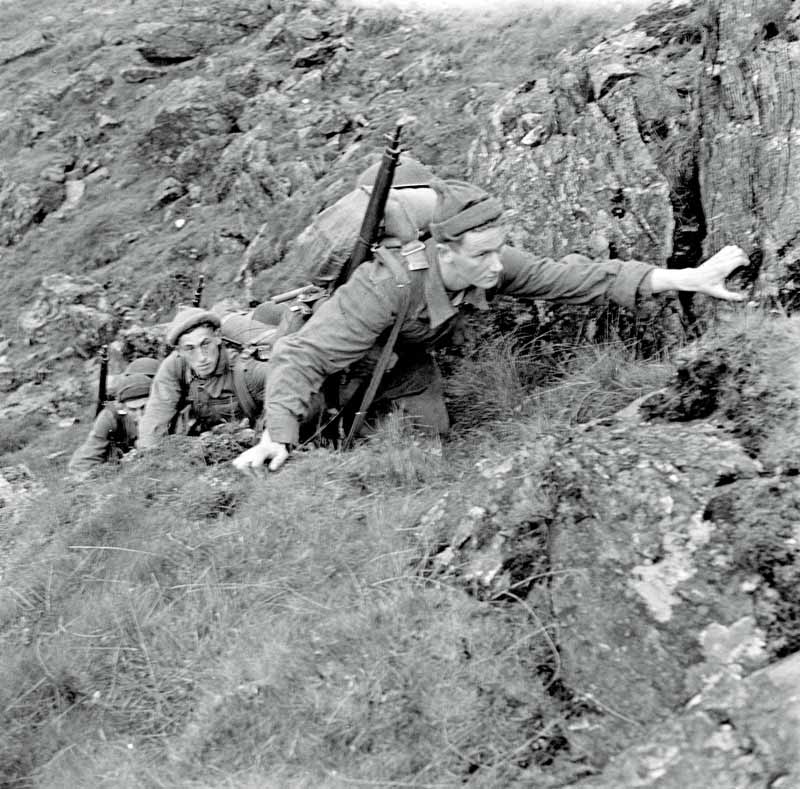

Canadian infantrymen take part in an exercise in May.[Lieut. Jack H. Smith/DND/LAC/PA-188919]

He was not amused. He looked at Pearkes, noted he was brave and would likely die waving his sword leading a frontal attack. Price, a dairy owner back home, should be sent back to Canada “where his knowledge of the milk industry will help on the national war effort,” said Monty cruelly. No one he deemed inefficient—including brigadiers, lieutenant-colonels and regimental sergeant majors—escaped the lash.

McNaughton had had few options in picking leaders, of course. The prewar Permanent Force (see “The in-between,” January/February 2023) had been tiny with only about 455 officers in a 4,200-man force. The militia was more than 10 times the size, but almost wholly untrained. There was hardly enough talent for an operational brigade, and McNaughton did understand that only experience could create vigorous commanders.

The present cadre, McNaughton said, was “a cover crop, to help the younger men through the wilting strains of the first responsibilities, in the same way that older trees are used to shelter saplings through the heat of the day.” To his credit, he identified some able younger officers—Guy Simonds, Bruce Matthews, Christopher Vokes, Charles Foulkes and Daniel Spry, for example—who, along with others, rose as the “cover crop” as older officers were returned to Canada for less strenuous commands.

By the autumn of 1941, the soldiers began Battle Drill training, a tough course that aimed to harden the soldiers and imprint on them the minor tactics they would need in action. They practised fire and movement over and over, and they ran physically demanding obstacle courses while live ammunition was fired over their heads. And the soldiers toughened up.

“I am working like Hell here we are taking our Basick [sic] Training all over only twice as hard,” Gunner Stanley Evans wrote to his wife. “We have wrote [sic] test after test and now we are going on a root [sic] march. We went for a five mile run the other day and another today so maby [sic] you will have a man when we come back.”

At the same time, Montgomery demanded large, complex training exercises that tested the troops’ stamina and their commanders’ abilities to plan and lead. The troops had been on exercises that reinforced road movement and anti-invasion operations, but Monty began to assess them in big offensive operations. Exercise “Tiger” in May 1942 pushed everyone hard. Some men marched 400 kilometres in a week, while their senior officers’ reputations were made and unmade.

Simonds, the brigadier-general staff of 1st Canadian Corps, for example, did well, and Monty noticed. Montgomery, not McNaughton, was turning the Canadians into soldiers by professionalizing their training.

There was another issue with McNaughton. He was a stickler for the rules governing how his soldiers would be used in the war. The War Office couldn’t simply tell Canadians where to fight. McNaughton was determined to keep his divisions together for the inevitable attack on France, something that greatly annoyed the British who had begun to have doubts about the Canadian’s ability to command in battle. Some Canadians had similar reservations, including General Harry Crerar who had been chief of the general staff in Ottawa and by 1942 was commanding the 2nd Division and then I Canadian Corps.

It was Crerar, the senior officer overseas while McNaughton was on leave in Canada, who pressed the War Office to give Canadians the main role in the Dieppe Raid. Crerar believed that unless Canadians saw action, their morale would crack.

The raid in mid-August 1942 was a disaster. One infantry battalion, the Essex Scottish, put 553 men on the main beach at Dieppe and only 53 returned to England. The rest were killed or captured. Those dreadful numbers were roughly similar in all the units. Dieppe had been intended to give the troops a taste of action, but it shattered some units.

Some soldiers, however, made the best of it: “I often wonder what you think of the raid at Dieppe,” James McKie of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry wrote. “I think we’ll be getting going one of these days soon now and it can’t come soon enough for me either. It’ll be a tough job but I have a lot of faith in these guys here and I know they will be just as tough as any squarehead if they get half a decent sort of break.”

Members of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps rehearse for the Dieppe Raid in England in August 1942. [DND/LAC/PA-113242]

Dieppe, perhaps, should have been interpreted differently. Canadian troops (and British planners) needed to be much better trained before they could successfully fight the Wehrmacht. Fortunately, there was more time before the troops would see continuous action.

The 1st Infantry Division and the 1st Army Tank Brigade participated in the Sicily invasion in July 1943, and they were joined by the 5th Armoured Division and I Canadian Corps Headquarters at the end of the year. The First Canadian Army had been split up, leaving only the 2nd and 4th

divisions and the 2nd Armoured Brigade in England, and McNaughton had been forced out by the end of 1943.

The army’s training continued until the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Only then would the long wait truly be over.

Advertisement