At half past 3 o’clock this morning, the government received official word that the invasion of Western Europe had begun. Word was also received that the Canadian troops were among the Allied forces who landed this morning on the northern coast of France. Canada will be proud to learn that our troops are being supported by units of the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Canadian Air Force. The great landing in Western Europe is the opening of what we hope and believe will be the decisive phase of the war against Germany.”

—Prime Minister Mackenzie King,

national radio broadcast, 8 a.m. EST, June 6, 1944

Captain Orville Norman Fisher depicts the D-Day assault. “The noise was unbearable,” he said. [Captain Orville Norman Fisher/CWM/19710261-6231]

The long-awaited day had finally arrived. After more than two-and-a-half years of planning, pinprick raids to test German defences, buildup of men, materiel and equipment in Britain, disagreements over assault areas, deception plans and last-minute weather concerns, the essential return to the European continent by Allied forces had commenced.

Despite Allied invasions of North Africa and Italy, the Soviet Union insisted another front was necessary to reduce German pressure on their homeland. In late 1943, the British and Americans agreed to open a second major front in France. As a result, the largest amphibious invasion in history was conceived: Operation Overlord.

Troops of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade (Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders) head ashore at Bernières-sur-Mer, France, on June 6, 1944. [Lieutenant Gilbert Alexander Milne/DND/LAC/PA-122765]

The scheme called for assaults on five landing areas (not beaches as is often erroneously stated) along a 100-kilometre stretch of Normandy coastline by 156,000 men in six infantry divisions, supported by armoured units. From west to east, the U.S. 4th Infantry Division would land at Utah, the American 1st and 29th at Omaha, the British 50th at Gold, the Canadian 3rd at Juno and the British 3rd at Sword. Airborne landings by the U.S. 82nd and 101st airborne divisions would take place on the western flank, while the British 6th Airborne Division (including the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion) would land on the eastern one.

Meanwhile, the Germans were acutely aware that an Allied invasion of northwest Europe was inevitable. In its simplest terms, it boiled down to a question of where and when.

In response, the Germans fortified the coast of Europe from the Franco-Spanish border in the south to the northern tip of Norway. Known collectively as the Atlantic Wall, it consisted of hundreds of kilometres of barbed wire and anti-tank ditches, millions of mines and tens of thousands of bunkers garrisoned by hundreds of thousands of soldiers, who manned mortars, machine guns, anti-tank weapons and artillery pieces.

Due to increasing demands placed on Germany by the war in the east, many sections of the Atlantic Wall were staffed by second-rate soldiers, including older men, those with medical conditions and converted prisoners of war. Plus, there was a lack of co-operation between the various groups responsible for the wall, a situation only partially resolved with the appointment of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel as commander of German army forces in northern France.

In April 1944, German officers inspect their defences at what became the Canadian landing area.[Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia]

The design for the Allied campaign involved a far-reaching deception plan collectively known as Operation Bodyguard. Its aim was to make the Germans think the invasion would occur somewhere other than Normandy.

Aerial and beach reconnaissance was carried out along the length of the northwestern European coastline, with more occurring outside of Normandy to make the Germans believe the invasion would take place elsewhere.

Similarly, Allied bombing and fighter operations systematically isolated Normandy from rapid German reinforcement. Like the aerial reconnaissance missions, however, more were carried out in other areas as part of the overall ruse.

Two fictitious armies were created to carry out this feint, code-named Operation Fortitude. The First U.S. Army Group was based in Kent in southeast England under Lieutenant-General George Patton. France’s Pas de Calais area, the closest point to Britain, was its purported target. The British Fourth Army, meanwhile, was stationed in Edinburgh, Scotland, to create the impression that it would invade Norway in conjunction with a Soviet attack.

Communication specialists simulated radio traffic between these armies. Dummy tanks, trucks and other vehicles constructed of wood, canvas and other materials were strategically placed to create the impression of a buildup of equipment prior to an invasion.

Among the first Allied soldiers to invade France were 117 members of ‘C’ Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

Personnel of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion train for the invasion in February 1944. [Lieutenant Strathy Smith/DND/LAC/PA-132785]

Among the first Allied soldiers to invade France were 117 members of ‘C’ Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. They jumped just after midnight on June 6, part of the lead element of Britain’s 3rd Parachute Brigade, dropped in advance as pathfinders to mark jump zones for the paratroopers who were to follow them.

The drop did not go as planned. Adverse weather conditions, poor visibility and other factors conspired to scatter the Canadians over a wide area, with some soldiers far from their intended drop zone. Twenty-year-old paratrooper Jan de Vries ended up several kilometres from his planned landing spot. “I wondered where the heck I was when I hit the ground,” he recalled. “I spent all night trying to find my way in the dark toward my rendezvous point near the coast, dodging enemy patrols the whole way.”

Despite these difficulties and stiff German resistance, the paratroopers set out to accomplish their assigned missions over the next few hours. But the cost was high. Of the 541 paratroopers who landed in Normandy, 34 were killed or wounded within the first 24 hours. Another 82 were captured, while several others were missing.

A few kilometres to the west of the Canadian’s drop zone, the Juno landing area stretched along eight kilometres of beach and included the seaside villages of Vaux, Graye-sur-Mer, Courseulles-sur-Mer, Bernières-sur-Mer and Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer. Once ashore, infantry battalions of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division under Major-General Rod Keller and Sherman tanks of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade under Brigadier Bob Wyman were to advance inland about 15 kilometres and link up with British units on either side of Juno.

In outline, the first wave was to consist of infantry battalions from the 7th and 8th brigades, each accompanied by Sherman tanks. Their job was to secure the beachhead, establish exits from the shoreline and advance to the high ground west of the city of Caen some 15 kilometres inland. In the second wave, the 9th Brigade’s infantry battalions planned to land with tanks and proceed inland to reinforce the lead brigades in anticipation of a German counterattack.

As so often happens in military planning, everything did not go according to plan.

Naval and air support for the landings was massive. An armada of more than 6,900 ships formed up in ports in the south of England. Canadian naval participation in the largest seaborne attack in history consisted of 10,000 sailors in 109 ships, several of which were outside the immediate invasion area.

Infantry ships, motor torpedo boats and a minesweeper off the port beam of HMCS Prince David just before dawn on D-Day. [Donovan James Thorndick/DND/LAC/PA-143818]

As the ships left British ports, minesweepers cleared the channels ahead of the fleet. Off the landing areas, destroyers provided fire support, while landing ships, infantry (medium), carried landing craft assault (LCA), the latter each capable of holding a platoon.

Landing craft, tank (LCT), each transported three specially modified amphibious duplex drive (DD) Sherman tanks. The addition of an inflatable canvas screen and two propellors allowed each tank to “swim” ashore so it could arrive on the shoreline with the infantry.

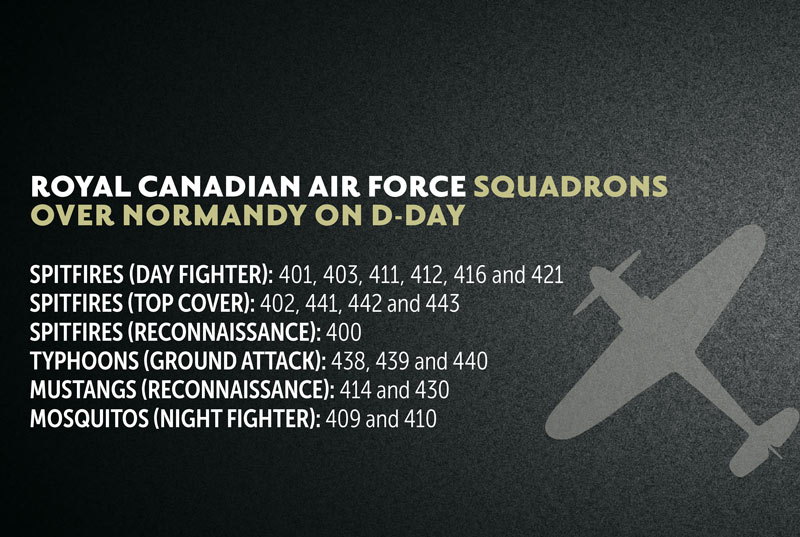

Some 11,000 aircraft were allocated to Overlord, resulting in a 35:1 ratio in favour of the Allies. As it turned out, Allied fighter aircraft did not encounter many Luftwaffe planes over Normandy on June 6, leaving Canadian and other Allied aircrew largely as spectators of the massive invasion.

The three Typhoon squadrons of 143 Wing saw the most action on D-Day, as each of them flew three ground-attack missions against defences on the Gold, Juno and Sword landing areas during the initial assault. An early evening armed reconnaissance by the wing resulted in strafing and bombing attacks against enemy tanks, trucks and troop carriers, which resulted in the loss of three aircraft and a pilot in 440 Squadron.

Meanwhile, as the Canadian flotilla approached Juno, a barrage of gunfire saturated the coast. Destroyers and specialized landing craft fired their heavy guns and rockets. Simultaneously, 96 self-propelled 105mm guns of four artillery regiments, embarked on 24 LCTs, zeroed in on specific fortified positions along the beaches. The 105s fired above the LCAs for 30 minutes.

But, as the soldiers who landed at Juno on D-Day quickly discovered, the preliminary naval and air bombardments had caused little damage to enemy positions ashore, manned by soldiers of the 716th Infantry Division, a coastal defence formation.

As the LCAs approached the shore ahead of the rest of the invasion fleet, Sergeant-Major Charlie Martin of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada suddenly realized his horizons had been reduced considerably. “All that remained within sight was our own fleet of ten assault craft, moving abreast in the early-morning silence…. We had never felt so alone in our lives.”

The units of the 7th Brigade under Brigadier Harry Foster, supported by tanks of the 1st Hussars, had Courseulles as their objective. The town was one of the most heavily fortified along the entire Normandy coast.

One strongpoint had a 75mm and an 88mm gun, plus two 50mm ones. Two more 75mm guns covered the town’s flanks, while 12 machine-gun pillboxes and concrete mortar emplacements added to the German defences.

Flight Lieutenant Eric Aldwinckle depicts the invasion action from above.[Flight Lieutenant Eric Aldwinckle/CWM/19710261-1230]

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles landed at their sections of Juno, known as “Mike Red” and “Mike Green” at 7:49 a.m., only to find the enemy defences on the west side were unscathed by the bombardment. As the unit’s war diary noted: “The bombardment having failed to kill a single German soldier or silence one weapon, these companies had to storm their positions ‘cold’ and did so without hesitation…. Not one man flinched from his task.”

Overcoming such heavily fortified positions required tank support. The Sherman tanks of ‘A’ Squadron, 1st Hussars, had launched 1,375 metres offshore while under fire. The leading Shermans arrived shortly after the infantry and brought much-needed direct fire on a well-defended 75mm position in support of an attack by ‘B’ Company.

‘B’ Company succeeded in its task, but at a heavy price. By the time the position was taken, it was down to a captain and 26 men. Meanwhile, the accompanying engineer assault party from the 6th Field Company lost two-thirds of its 39 men.

To ‘B’ Company’s right, ‘D’ Company jumped from its landing vessels into waist-deep water and waded ashore toward some sand dunes. With the assistance of five Shermans, it captured German positions along the dunes, then headed inland toward the town of Graye-sur-Mer.

‘A’ and ‘C’ companies landed afterward and moved to pre-assigned objectives. Along the way, they mopped up any enemy positions still intact.

‘C’ Company of The Canadian Scottish Regiment had been detached from its parent unit to take part in the first wave. Its mission was to attack a pillbox on the extreme right flank of Juno, the area code-named “Mike Green.” It landed to find the enemy position abandoned.

The company moved on to its next objective, a protected field gun battery at a chateau. The Canscots quickly overran the position.

On the 7th Brigade’s other area of the beach, “Nan Green,” The Regina Rifle Regiment landed at 8:05. Like the Winnipeggers, they had two companies in the assault and two in reserve. While ‘A’ Company attacked a strongpoint and held the enemy’s attention, ‘B’ Company was able to land unopposed and enter Courseulles. With the assistance of Shermans and Royal Engineer assault vehicles, it began to clear the town.

Meanwhile, ‘A’ Company had outflanked the German beach position and began to move inland, but was forced back to the area of the enemy strongpoint. With armoured support, the company finally secured the position at 2 p.m.

When the Reginas’ reserve companies landed, the incoming tide had covered several of the beach obstacles. As a result, the LCAs carrying ‘D’ Company struck underwater mines, leaving less than 50 men to move inland. ‘C’ Company fortunately landed safely, and the two companies advanced to successfully capture the bridge at Reviers.

Although a beachhead had been secured, not all Canadian soldiers moved off the landing areas as soon as they should have, especially at Courseulles. This was due to limited exits through the seawall, sand dunes, mines and other obstacles, which required specialized equipment and troops that were not immediately available in sufficient numbers.

But some exits were created through the extraordinary efforts of soldiers such as Sapper John Duval of the Royal Canadian Engineers’ 16th Field Company. At about 9:30 a.m., Duval, an armoured bulldozer operator, single-handedly created three vehicle exits over the seawall within 20 minutes, under heavy mortar and small arms fire. He received the Military Medal for his efforts.

While 7th Brigade was carrying out its mission, to the east Brigadier Ken Blackader’s 8th Brigade was engaged in similar tasks. The Queen’s Own was assigned the area known as “Nan White” at Bernières-sur-Mer, while The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment landed on “Nan Red” at Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer.

Troops of Le Régiment de la Chaudière disembark from landing craft at Bernières-sur-Mer, France, on D-Day. [Lieutenant Frank L. Duberville/DND/LAC/PA112641]

At Bernières, the Queen’s Own faced a field gun and four concrete machine-gun nests stretched along 275 metres of seawall. The two leading companies were supposed to land to the right of the position to capture it from a flank, but wind had pushed the landing craft to the left and ‘B’ Company landed in front of the position.

Armoured support was delayed due to rough seas, which required the LCTs to beach their Fort Garry Horse tanks rather than launch them offshore, so ‘B’ Company attacked the enemy defences alone. Half of the company was killed or wounded in the first few minutes.

As had happened elsewhere along the shoreline, ‘B’ Company’s battle allowed ‘A’ Company to get off the beach, but it got pinned down once over the seawall. Heavy fighting followed as the company slowly overcame enemy resistance.

The Queen’s Own reserve companies landed 25 minutes after the assault companies. ‘D’ Company met little resistance, its commander Major James N. Gordon describing the enemy as “mere boys” who “ran away.” As a result, they cleared the beach in four minutes and moved on to the southern end of Bernières.

Half of the LCAs carrying ‘C’ Company (and battalion headquarters) struck mines, forcing survivors to swim or wade ashore. By 8:45 a.m., both reserve companies were moving toward the far end of Bernières and the reserve battalion, Le Régiment de la Chaudière, had landed.

The Queen’s Own gained a double distinction in the action. The unit broke through the Atlantic Wall in less than an hour, but it also suffered the heaviest losses of any Canadian battalion on D-Day: 61 killed and 76 wounded.

As so often happens in military planning, everything did not go according to plan.

Meanwhile, the North Shores landed to the left of the Queen’s Own at 8:10. The unit’s primary target was a fortified 50mm gun position in Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer in the centre of the battalion’s sector.

‘B’ Company was to capture the nest by moving south and taking it from the rear, but naval and aerial gunfire had failed to damage the position. Plus, as they had with the Queen’s Own, the Fort Garry Horse tanks supporting them landed late due to the rough seas and were not immediately available.

Salvation took the form of a battalion 6-pounder anti-tank gun, which took out a pillbox. The unit’s 2-inch mortars joined in the attack just before Garry’s tanks arrived to complete the mission.

To the west, ‘A’ Company faced tough opposition as it cleared the beach, but it persevered and linked up with the Queen’s Own around 9:50. ‘C’ and ‘D’ companies landed at 9:45, cleared the western half of the town and advanced inland toward Tailleville to clear another defensive post.

Units of 9th Brigade under Brigadier Doug Cunningham were in reserve and did not land until about noon. The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders came ashore at Bernières, along with tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers. A massive traffic jam greeted them, which delayed their move off the beach until noon.

At that time, Canadian soldiers began to advance inland on a broad eight-kilometre front. They moved steadily forward throughout the day and by nightfall had established an uneven, but connected, defensive line about six kilometres from the coast. The Canadians had reached Creully in the west and Villons-les-Bussons in the east.

Despite facing one of the toughest landing areas, the Canadians had penetrated further inland than the troops of any other country. But their magnificent achievement was costly. Of the approximately 14,000 Canadians who landed on D-Day 1,096 became casualties, including 381 killed.

For most of the Canadians involved, D-Day was their first battle of the war. Soldiers from across the country—the Maritimes, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies and the West Coast—had faced a battle-hardened, experienced enemy. Like their fathers a generation earlier, the Canadians didn’t lack courage.

Several weeks of tough fighting followed, including powerful German armoured counterattacks during the next few days, before the battle for Normandy concluded near the end of August. The Canadians’ actions on the beaches and fields of Normandy helped lead the way to the final and total collapse of Hitler’s much-vaunted Thousand-Year Reich less than a year later.

German prisoners captured by Canadian troops on D-Day are escorted to landing craft on Juno Beach.[Lieutenant Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-133742]

Advertisement