His death was not combat-related so his story is easily overlooked among the hundreds who lost their lives in battle. Wood, a decorated Second World War veteran, died preparing comrades for the dangers they would face in combat.

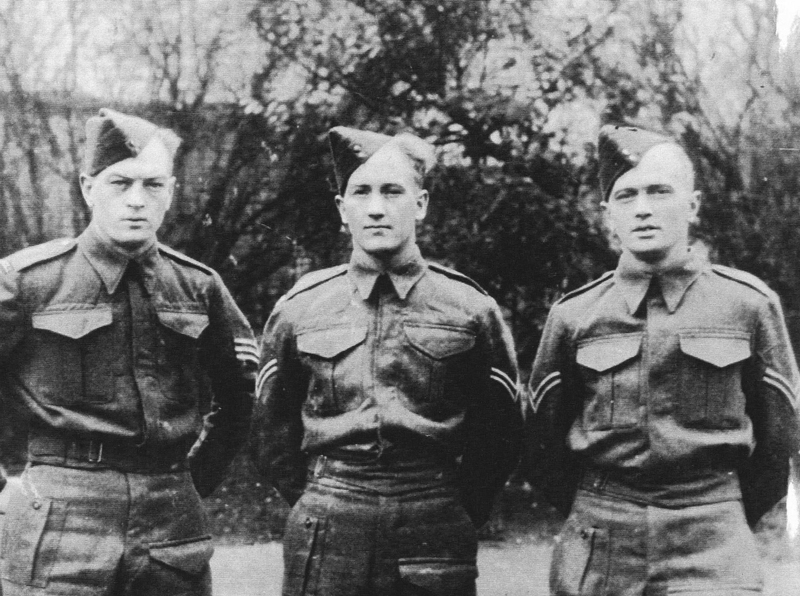

Wood left school during the Great Depression to earn a living, working several different jobs in Vancouver. He joined the reserves in 1933, and was transferred to the regular force in 1936, starting his career as a private in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. He shipped out with his regiment to Scotland in December 1939.

Princess Patricia of Connaught inspects the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry at Bramshott Military Camp. [Legion Magazine]

He fought through the Sicily campaign and then on to Italy where he took part in the advance to Campobasso, the crossing of the Moro River and the battles at Villa Rogatti and Ortona. He was appointed acting company sergeant major in September 1944.

The Patricias were ordered to secure a bridgehead on the Savio River in northern Italy on Oct. 20. To do so, they had to cross ground studded with mines while under heavy fire from machine guns, mortars and artillery.

Wood was among the first to arrive and braved enemy fire while helping 17 men make their way across the swollen river.

Once his company was on the other side, they sussed out concealed machine-gun positions.

Wood immediately attacked the position with grenades.

Wood worked his way forward to within 75 metres of a machine-gun nest, dashed across an open stretch of ground and tossed hand grenades inside, killing two and forcing three into the open where they were taken as prisoners.

Members of the Royal Canadian Regiment take over guard duties at Compound 66, where North Korean officers and other ranks are enclosed, in June 1952. [Paul Tomelin, Library and Archives Canada—PA188770]

Over the two-day operation, Wood “showed great courage and a complete disregard for his own personal safety…at all times his actions, which were far beyond the normal call of duty, were an inspiration,” reads his citation.

In December, the Canadians were pulled out of Italy and sent to Europe, where Wood was to end his war; though he volunteered to serve in the Pacific, the fighting finished before he was dispatched.

When he went to investigate, the mine exploded.

But he stayed with the regiment, joining the regular force after the war. He qualified to teach the Arctic indoctrination course and earned the Canadian parachute badge.

Under pressure at home following his marriage in 1947, he left the army in September 1949 to work for a Calgary oil company.

In November 1950, when the Special Service Force for Korea was organized, he signed up and was named regimental sergeant major for the 2nd Battalion when the Patricias shipped out.

Canadian soldiers clean their weapons outside a bunker in December 1952. [J.R. Marwick, Library and Archives Canada—PA170774]

Wood was seriously wounded and was transported to a field hospital, where he died after surgeons spent six hours trying to save his life.

Wood, the first of 516 Canadian military personnel to die in Korea, was buried in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busan. A lake near Grande Prairie, Alta., was named in his honour.

Advertisement